Following the spectacularly successful Galileo mission from 1995 to 2003, the scientific community yearns for a return to Jupiter. The Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory have issued a joint proposal for a new Jupiter probe called Juno.

Juno would be NASA’s second probe in the New Frontiers series of medium-cost explorers and launch no later than 2010. According to SwRI’s Bill Gibson, Juno is “very simple as planetary missions go, so we can keep the cost down. … Juno uses conventional propulsion. And we’ve limited our study to Jupiter. It’s a plenty big target!”

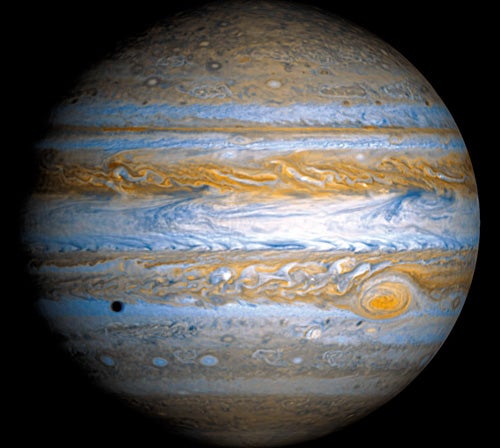

Data returned from observations made by Galileo’s orbiter and probe left many questions: Why is there so little water in Jupiter’s clouds when models predicted otherwise? Is the structure at the probe’s entry site typical of other locations on Jupiter? What is the planet’s core made of, and how extensive is it? What is the nature of the polar regions, especially as it relates to Jupiter’s immense magnetic field?

Equipped with a plasma physics suite of instruments, Juno will improve on Galileo’s atmospheric science. “The Galileo probe was a single-point measurement,” says Gibson. “Some results were ambiguous. With Juno, we can study the jovian atmosphere and magnetosphere over a year, and do it planet-wide.”

Juno’s coinvestigator, NASA/Goddard’s Jack Connerney, explains, “Juno’s orbit puts us right at the cloud tops with a series of well-timed passes, so that we can make a grid around Jupiter. We’ll map the [magnetic] field precisely.”

Juno’s elliptical orbit will range from just 2,796 miles (4,500 kilometers) above the cloud tops to 40 Jupiter radii (roughly 2,856,000 km). Flight engineers will chart Juno’s orbit and map Jupiter’s gravity. As the craft changes speed, the Doppler shift in its signals will reveal the subtle tug of Jupiter’s gravity on Juno. These measurements will be the most accurate to date, enabling researchers to determine the mass and size of Jupiter’s core.