(Inside Science) — Over the past several years, scientists have published research suggesting that people’s brains change after spending longer than a few months in space. These studies started because astronauts experienced issues like vision problems and swollen optic nerves upon returning to Earth after long missions.

Researchers are now wondering whether these extended trips to space damage the brain. In a new study of five male cosmonauts (Russian astronauts), researchers looked at levels of different proteins in the blood that are often also seen in people with some sort of head trauma or brain disease. They found that on average, the cosmonauts had higher levels of some of the proteins in the three weeks following the mission than before.

Dr. Donna Roberts, a neuroradiologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston who did not contribute to the new paper, said that more studies need to be done to determine if these changes are clinically significant, but that the new paper is “an example of the type of tests we need to start doing more of” to better understand the effects of the brain’s changes during long-duration spaceflight.

The effects of long-term space travel on humans

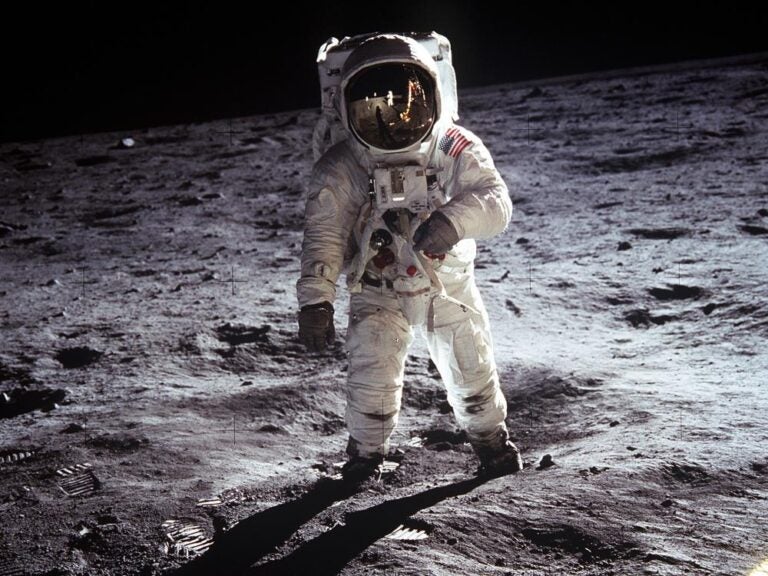

For over twenty years, humans have been visiting the International Space Station, which orbits Earth more than 200 miles above the planet. A typical trip lasts about six months. The space station is in free fall around Earth, so people on the space station experience a state of near weightlessness. Such “microgravity” is thought to be the main cause of a number of changes the human body can experience while in spaceflight, including the loss of muscles and bone density.

In the last couple of years, brain imaging has also revealed a loss in volume of grey matter, which contains the cell bodies of neurons, and an increased volume of cerebrospinal fluid. Roberts, who uses imaging to study the effect of spaceflight on the brain, has published research showing that in some people who have had long missions on the ISS, their brain has moved up in their head towards the top of their skull, and cerebrospinal fluid occupies more space below and in the center of the brain.

But researchers don’t know what these brain changes might mean for people’s health and cognition. Dr. Peter zu Eulenburg, a co-first author of the new study, published online Oct. 11 in JAMA Neurology, said the previous studies raised questions: “Is there any damage to the brain? Is this really harmful for the cosmonauts?”

Looking at blood for signs of brain damage

To look for evidence of brain injuries, zu Eulenburg and his colleagues measured the levels of five different proteins in the blood of five male cosmonauts both before and after approximately six-month trips to the space station.

These proteins are biomarkers that “can tell us about the status of the brain without opening up the brain,” said Keisuke Kawata, a neuroscientist at Indiana University Bloomington. Kawata, who studies repetitive head impacts and did not contribute to the study, said that the best fluid for studying biomarkers is cerebrospinal fluid in the brain and spinal cord, but accessing it requires an invasive spinal tap. Drawing blood is much easier, and blood “is the second-best biological fluid to test the brain health,” he said.

The biomarkers in the study can be used “to indirectly evaluate the extent of damage” due to neurodegeneration or a traumatic injury, said zu Eulenburg, who is a neurologist and professor of neuroimaging at the German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders. Neurofilament light chain, for example, is a structural protein that maintains neurons’ axons, which transmit signals to other neurons.

In a healthy person, “you shouldn’t be detecting much of those structural proteins in the blood,” Kawata said. But if someone has a neurodegenerative condition, the proteins dislodge from the neurons and can get into the bloodstream.

Interpreting the results

The researchers measured five proteins 20 days before launch and calculated the average level for each protein across the five cosmonauts. They then compared this to the average level one day, one week, and 20 to 25 days after the cosmonauts returned to Earth.

Two of the proteins had elevated levels both one day and one week after the missions. These levels dropped over the next two weeks, but remained above the cosmonauts’ baseline level from before the missions. A third protein wasn’t significantly elevated in the first week after returning and had dropped below the baseline after three weeks, so it wasn’t indicative of potential brain damage. For the final two proteins, the researchers typically look at the ratio of one to the other. The ratio dropped after the cosmonauts returned, a trend that is sometimes seen in people with a neurodegenerative condition.

zu Eulenburg said that the fact that some levels remained elevated for the entire three weeks was “very surprising,” and the results “verified brain injury as a consequence to long-duration exposure to microgravity.”

“This is obviously a pilot study, but the data quality and the analytics are so robust that I have no doubt in the overall effect,” he said.

The seriousness of these effects remains uncertain. Roberts said the paper contains “initial data suggesting that there is some type of injury to the brain,” but cautioned that more work needs to be done to show the effect on astronauts’ health. Kawata said the paper is not evidence that if you go to space, you’re going to get Alzheimer’s disease, for example.

Both Roberts and Kawata would like future studies to measure the biomarkers for longer than three weeks after astronauts return, as well as while they are on the space station, which would help determine if the elevated levels are due to time spent in microgravity, rather than the change in gravity upon return, or the intense force experienced during landing.

Roberts said understanding the cause of the elevated biomarkers would help space agencies figure out which sorts of measures would best counteract the effects. zu Eulenburg thinks time spent in microgravity is the most likely cause, since imaging studies have shown that changes in the brain don’t occur for people on shorter trips, so the elevated levels might start while astronauts are still in space.

Kawata said it shouldn’t be a big problem if biomarkers are only elevated for a couple of weeks in total. But zu Eulenburg said via email that three weeks of elevated levels are a sign of a “substantial” reparatory process. And other studies have shown that changes in the brain and cognitive effects last for at least several months after spending months in space, suggesting that elevated biomarkers could last longer than a couple of weeks.

“I would feel very cautious about doing a one-year mission aboard the [space station] without sufficient countermeasures in place,” said zu Eulenburg.

Roberts said she feels confident that science will be able to find ways to protect astronauts from adverse effects. “Ultimately our goal is to become a multiplanetary species… but we have to be smart about it along the way.”

This story was originally published with Inside Science. Read the original here.