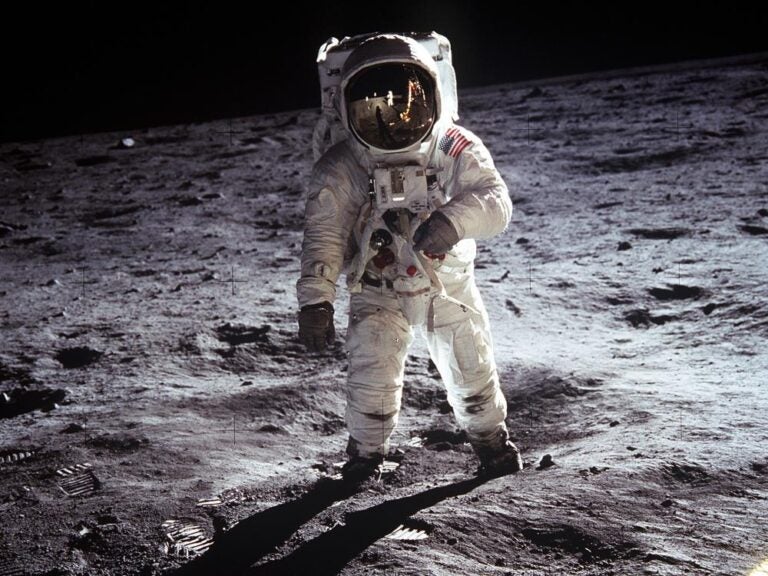

Better understanding the many effects of a low-gravity environment on the human body is important for preparing for spaceflight missions, the researchers said. The more researchers can understand about how spaceflight affects human bodies, the better agencies like NASA can prepare and protect their astronauts.

The researchers published their findings in a recent paper in the journal Scientific Reports.

Our bodies in space

Spaceflight seems to affect the human body in several ways. Astronauts’ immune systems get weaker in space, past studies have found. And some disease agents seem to get deadlier after spending time in space. A previous study also found that a type of the bacteria Salmonella that had spent some time in space caused more serious disease than the same type of bacteria that had stayed on Earth.

“As flights get longer and more complex, I think it increases the potential for food-borne illnesses to occur,” said Declan McCole, a biomedical researcher at the University of California, Riverside, and an author of the new study.

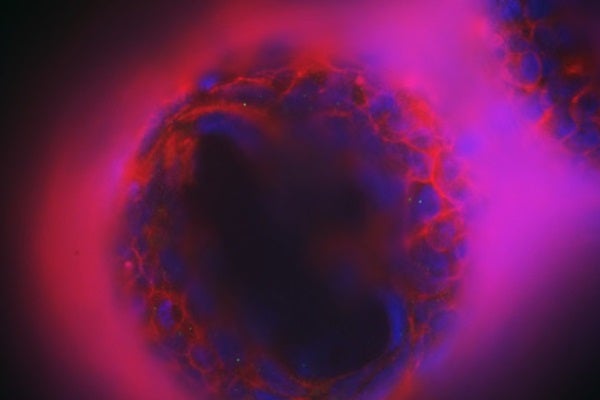

McCole and his team created a lab experiment to study the effects of microgravity on human intestinal epithelial cells, which make up the lining of the intestine. These gut cells form an important barrier that keeps us from getting sick after we eat food contaminated with disease-causing microbes.

Gut cells in low gravity

The team grew the gut cells on tiny spherical beads and placed the beads in a device called a rotating wall vessel full of fluid. The vessel rotates constantly so that the beads never hit the walls, mimicking the low-gravity environment of spaceflights.

The researchers removed the cells from the vessel and compared them with gut cells that hadn’t gone through simulated microgravity. When they exposed both groups of cells to a harmful agent (alcohol, in this case), the ones that didn’t experience microgravity held up much better. The barrier they formed had only mild flaws, while the cells that came out of the rotating wall vessel had more serious defects. These defects could let disease agents travel from intestines to other parts of the body.

The two groups showed this difference even up to 14 days after cells had been taken out from the rotating wall vessel. This implies that even after returning from Earth, the epithelial cells lining astronauts’ guts may not be as strong for a while.

The effect would probably go away by itself, McCole said, because human intestines grow new epithelial cells often. But understanding what effects microgravity might have on human intestines could help space agencies make better plans for their astronauts.