The Moon’s surface presents an unforgivingly harsh environment. As it lacks a magnetic field, it is exposed to levels of hazardous radiation 150 times greater than that on Earth. Without an atmosphere, it is fully vulnerable to deadly coronal mass ejections from the Sun, as well as a perpetual rain of impacting meteorites. And its temperatures range from extremes of 260 degrees Fahrenheit (127 degrees Celsius) in the daytime to –280 F (–173 C) during lunar night.

For all these reasons, prospective lunar explorers are increasingly considering an alternative to living on the Moon’s surface: living beneath it, in subsurface caves. Over the past 20 years, images taken from satellites orbiting the Moon have revealed hundreds of large pits lined with ledges that appear to overhang their floors. The hope has been that these could lead to even more cavernous spaces, such as lava tubes that could be left over from volcanic eruptions billions of years ago. But evidence so far of these more extensive tunnels had been lacking, leading to decades of debate.

Now, a new analysis of radar observations provides some of the best evidence yet that at least one such pit, located in Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), leads to an underground tunnel that extends at least a hundred feet (“tens of meters,” the authors write) — and possibly much longer. The work was published July 15 in Nature.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence for lunar caves, which are rapidly turning into a viable plan to shelter future permanent lunar outposts.

Lunar pits uncovered

The existence of lunar lava tubes was first proposed half a century ago by planetary geologist Ronald Greeley using data gathered by the Apollo missions. Lava tubes are hollow channels beneath the lunar surface through which molten lava once flowed. When the lava flows cease, the remaining channel can structurally support itself as an underground chamber.

On Earth, lava tubes are no wider than 100 feet (30 meters). But engineering studies have shown that under the weaker lunar gravity, lava tubes up to 1,260 feet (385 meters) wide could exist 210 feet (65 meters) below the surface, assuming a rock density similar to that of the returned Apollo samples. These suspected lava tubes remain hidden beneath the surface, but some reveal their presence by “skylights,” or collapsed pits where a section of the tube’s roof has collapsed, opening a gateway to the subsurface tube.

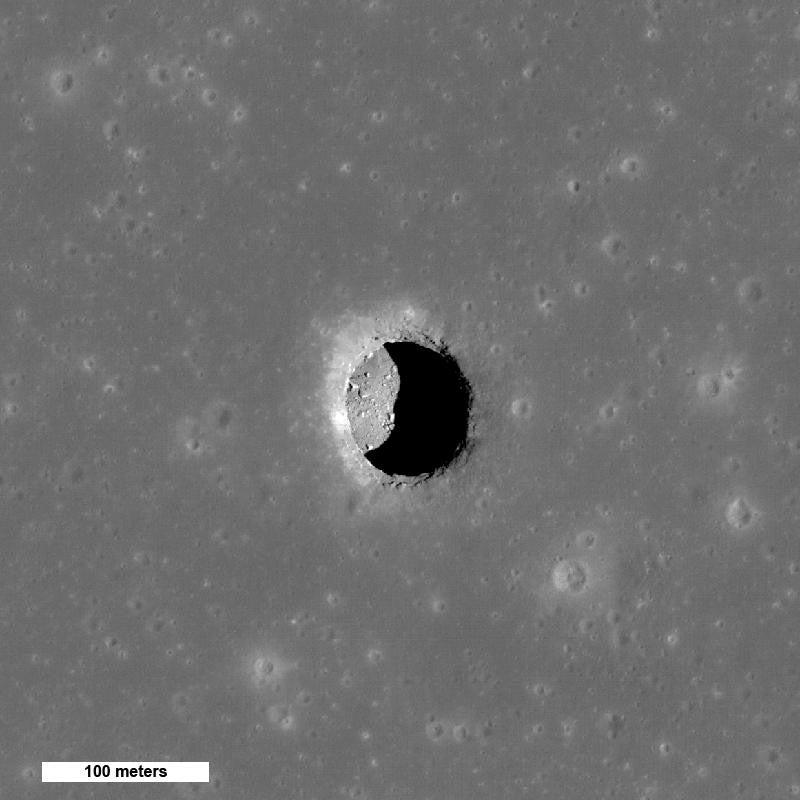

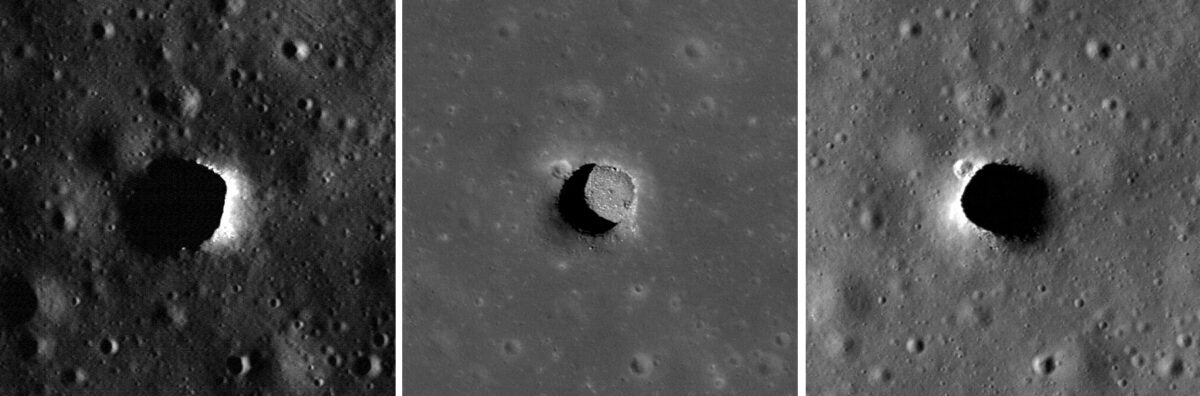

Scientists first recognized lunar pits 15 years ago in images from Japan’s Kaguya and NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Since then, more than 200 skylight-like pits ranging from five to 300 meters wide have been found with the additional help of India’s Chandrayan and China’s Chang’e orbiters.

A pit on the surface of the Moon is not necessarily evidence that an underground lava tube extends from it. But intriguing further evidence of the existence of lunar lava tubes has emerged over the past decade. In 2011, NASA flew the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission to the Moon, which mapped the lunar gravity field at very high resolution. The GRAIL data showed areas of the Moon with higher-than-average gravity as well as areas with a “gravity deficit,” indicating a corresponding deficit of mass.

Of the pits observed so far, about a dozen have shown promise of being skylights leading to underground chambers. The first was spotted in the Marius Hills, a former volcanic hot spot on Oceanus Procellarum, by the Japanese Kaguya orbiter in 2008. A 2017 study combining the Kaguya radar and GRAIL gravity data revealed a match between the areas showing a double radar echo and the locations of gravity deficits — a strong indication of subsurface voids at the so-called Marius Hills Pit.

A new Tranquility Base?

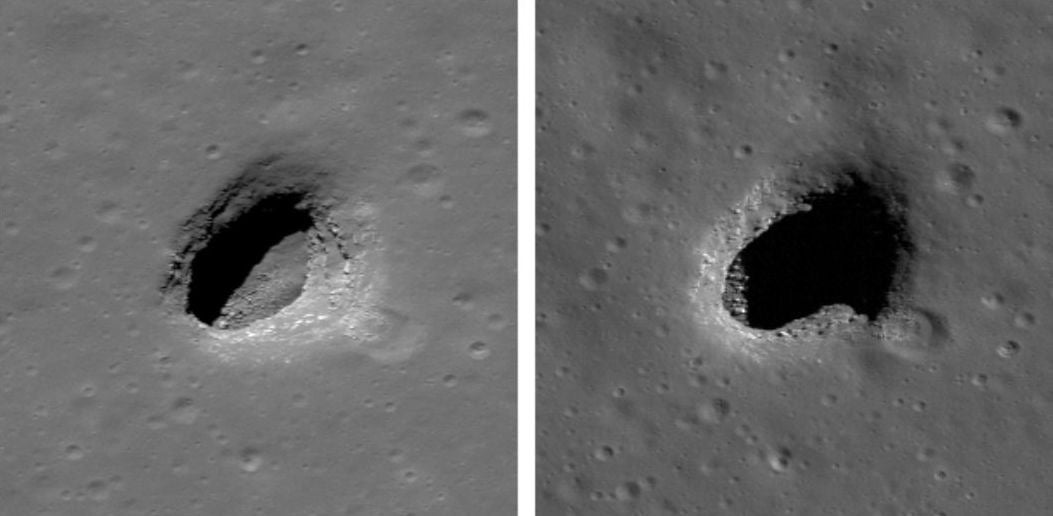

Other promising skylights were located in 2011 by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, including one in Mare Tranquillitatis that spans 210 feet (65 meters) and features a boulder-strewn floor 120 feet (36 meters) below the surface.

The new work uses advanced signal analysis techniques to study the radio signal reflected from Mare Tranquillitatis using LRO’s Miniature Radio Frequency instrument in 2010. The radio return signal is consistent with an initial bounce off the Moon’s surface and a second bounce from the floor of a subsurface chamber.

3-D modeling of the radar signal, accounting for the viewing angle of the satellite, indicates that an underground conduit extends west of the pit and the collapsed rock pile at its center. Further observations could determine whether the conduit continues in the opposite direction, to the east, the team says.

The result is “the first direct evidence of an accessible lava tube under the surface of the Moon,” Lorenzo Bruzzone, a remote-sensing expert at the University of Trento, said in a press release. And, it “suggests that the [Mare Tranquillitatis pit] is a promising site for a lunar base, as it offers shelter from the harsh surface environment and could support long-term human exploration of the Moon,” the authors write.

How to settle a Moon cave

In the near-term, NASA’s plans for the Artemis program call for landing and establishing a base near the lunar south pole. This location offers access to ice within permanently shadowed polar craters, which will be a valuable water resource for humans and could be used to create hydrogen and oxygen rocket fuel. Additionally, perpetual solar power is available, as the Sun never sets on the high rims of polar craters.

But in the mid-term, when a permanent, sheltered, and secure base is needed on the Moon, underground caves and lava tubes are a natural next step.

Scientists still have a lot of research to do on the long-term stability of lunar subterranean voids for future habitation. Seismic activity and meteor impacts have the potential to collapse thin-roofed lava tubes, with disastrous results for habitations either within them or on the surface above them. We know such thin-roofed lava tubes can form when a surface layer of lava solidifies on top of a molten flow; a subsequent collapse reveals a winding, sinuous rille. An example is Rima Hadley on eastern Mare Imbrium that was explored by Apollo 15 in 1971.

Any potential lava tubes would need to be explored — either by humans or robotic equivalents — to confirm their actual habitability. The European Space Agency (ESA) is studying several concepts, including a tethered micro-rover that would descend into a skylight to explore what lies below.

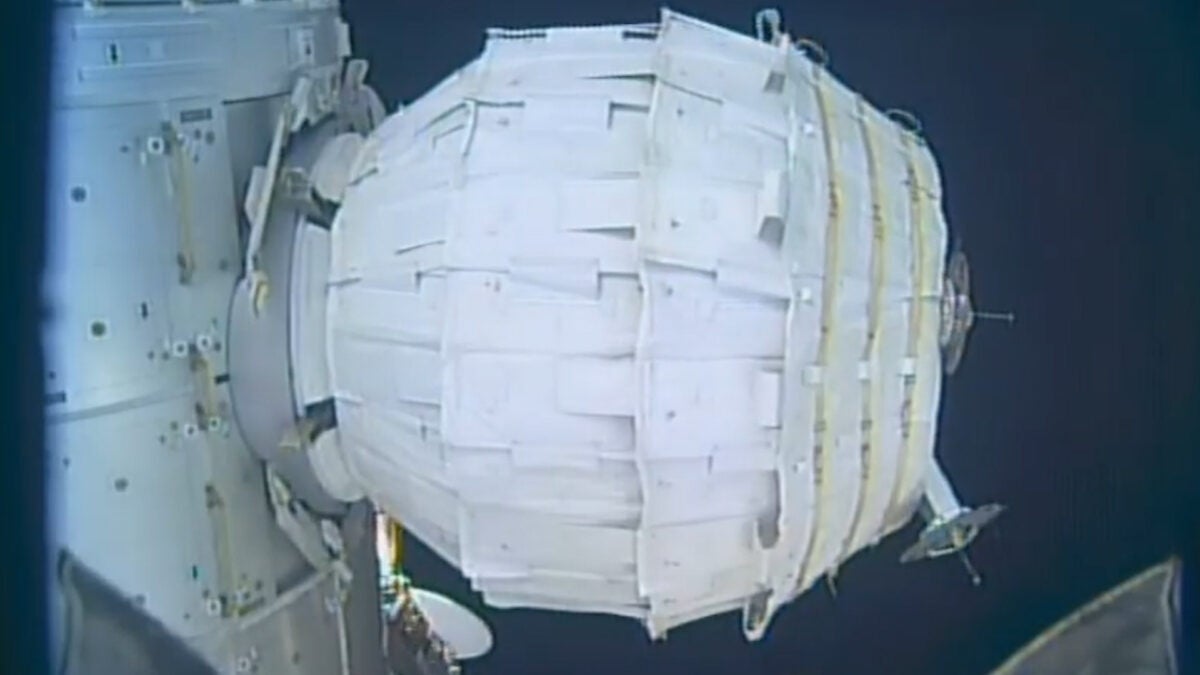

But should those issues be overcome and a suitable lava tube identified, a habitat solution may already be at hand. An inflatable module dubbed the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) has been attached to the International Space Station since 2016 for long term testing. A similar inflatable habitat architecture could be used inside lunar lava tubes.

Studies have investigating sealing off and pressurizing a lava tube itself for use as a lunar habitat, but that plan is fraught with unknowns. A more practical venture might be to deploy an autonomous construction robot like an oversized Roomba that would clear and flatten the floor of a lava tube. Inflatable modules then placed in the shelter of a lava tube could quickly establish a permanent base on the Moon. Additional data returned by LRO’s Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment show the temperature within the Tranquillitatis skylight remains a benign 63 F (17 C), simplifying the design of an inflatable habitat.

It would be ironic if humankind were to evolve through 30 millennia and achieve routine interplanetary spaceflight, only to revert off-world to once again become cave-dwellers. But lunar lava tubes show real promise to shelter future astronauts on the Moon.