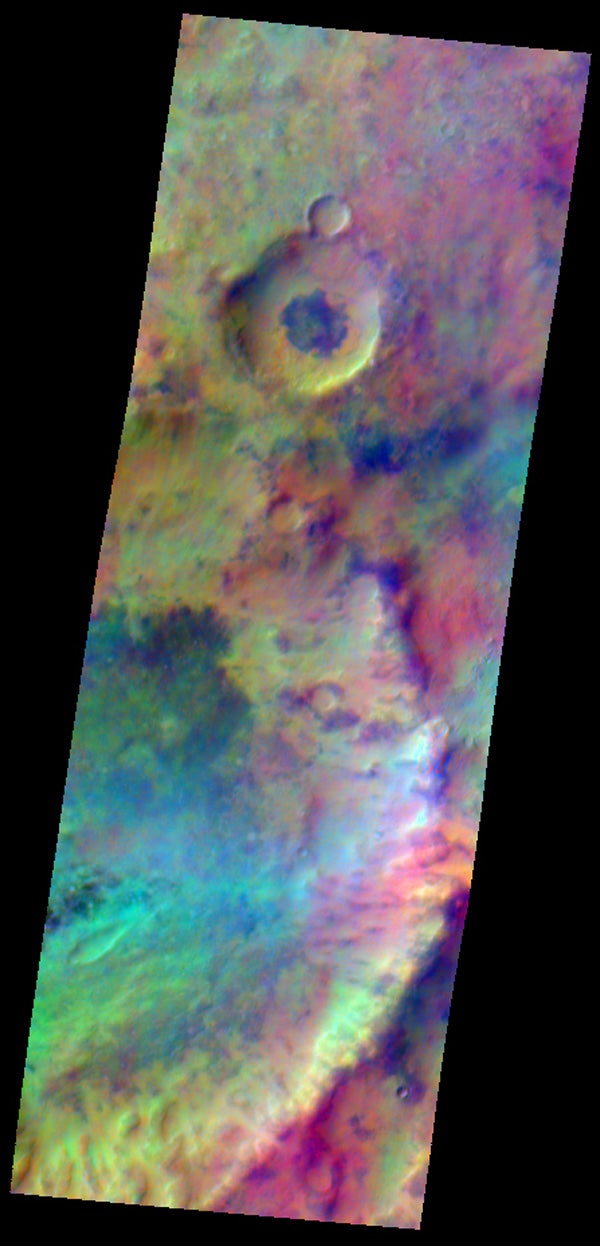

The image shows an area 19.8 miles (31.9 kilometers) by 54.9 miles (88.3 kilometers) in the southern highlands of Mars. It is a result of altering the orbit of Odyssey so that the spacecraft passes over the dayside of Mars earlier in the afternoon when the ground is warmer and emits more strongly in the infrared frequencies detected by THEMIS. Prior to beginning the slow shift in orbit September 30, 2008, Odyssey was looking down at the ground where the local solar time was about 5 p.m. When the shift was completed on June 9, 2009, the orbiter and camera were looking down at the ground where the local solar time was about 3:45 p.m.

In the image, dark areas mark exposures of relatively cold ground with abundant bare rock, while warmer basaltic sand covers the light blue-green regions. Reddish areas likely have a higher silica content, due either to a different volcanic composition or to weathering.

NASA’s long-lived Mars Odyssey spacecraft has completed an 8-month adjustment of its orbit, positioning itself to look down at the dayside of the planet in mid-afternoon instead of late afternoon.

This change gains sensitivity for infrared mapping of martian minerals by the orbiter’s Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera. Orbit design for Odyssey’s first 7 years of observing Mars used a compromise between what worked best for the infrared mapping and for another onboard instrument.

“The orbiter is now overhead at about 3:45 p.m. instead of 5 p.m., so the ground is warmer and there is more thermal energy for the camera’s infrared sensors to detect,” said Jeffrey Plaut, project manager for Mars Odyssey at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Odyssey discovered some important minerals by mapping during the first 6 months of the mission when the orbit geometry provided mid-afternoon overpasses. One key example — finding salt deposits apparently left behind when large bodies of water evaporated.

“The new orbit means we can now get the type of high-quality data for the rest of Mars that we got for 10 or 20 percent of the planet during those early six months,” said Philip Christensen, principal investigator for THEMIS at Arizona State University, Tempe.

The orbital shift to mid-afternoon will stop the use of one of three instruments in Odyssey’s Gamma Ray Spectrometer suite. The new orientation soon will result in overheating a critical component of the suite’s gamma-ray detector. The suite’s neutron spectrometer and high- energy neutron detector are expected to keep operating. The Gamma Ray Spectrometer provided a 2002 discovery of water-ice near the martian surface in large areas. The gamma-ray detector has also mapped global distribution of many elements, such as iron, silicon, and potassium.

Last year, before the start of a third 2-year extension of the Odyssey mission, a panel of planetary scientists assembled by NASA recommended the orbit adjustment to maximize science benefits from the spacecraft in coming years.

Odyssey’s orbit is synchronized with the Sun. Picture Mars rotating beneath the polar-orbiting spacecraft with the Sun off to one side. The orbiter passes from near the north pole to near the south pole over the day-lit side of Mars. At each point on the martian surface that turns beneath Odyssey, the solar time of day when the southbound spacecraft passes over is the same. During the 5 years prior to October 2008, that local solar time was about 5 p.m. whenever Odyssey was overhead. (Likewise, the local time was about 5 a.m. under the track of the spacecraft during the south-to-north leg of each orbit, on the night-side of Mars.)

On September 30, 2008, Odyssey fired thrusters for 6 minutes, putting the orbiter into a “drift” pattern of gradually changing the time of day of its overpasses during the next several months. On June 9, Odyssey’s operations team at JPL and at Lockheed Martin Space Systems in Denver, Colorado, commanded the spacecraft to fire the thrusters again. This 5.5-minute burn ended the drift pattern and locked the spacecraft into the mid-afternoon overpass time.

“The maneuver went exactly as planned,” said Gaylon McSmith, Odyssey mission manager at JPL. In another operational change motivated by science benefits, Odyssey has begun making observations other than straight down in recent weeks. This more flexible targeting allows imaging of some latitudes near the poles that are never directly beneath the orbiter and allows faster filling in of gaps not covered by previous imaging.

“We are using the spacecraft in a new way,” McSmith said. In addition to extending its own scientific investigations, the Odyssey mission continues to serve as the radio relay for almost all data from NASA’s Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity. Odyssey’s new orbital geometry helps prepare the mission to be a relay asset for NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory mission, scheduled to put the rover Curiosity on Mars in 2012.