After a long winter of inactivity, NASA’s Spirit rover has stirred from its slumber. The intrepid spacecraft has moved from its perch for the first time in nearly 7 months, continuing its exploration of Mars’ Columbia Hills. Mission controllers parked Spirit for the long southern winter because it couldn’t get much power — the winter Sun lay low in the sky, and a fine layer of dust covered the solar panels. To maximize solar radiation, scientists maneuvered the probe onto an 11° slope facing the Sun.

Meanwhile, Spirit’s twin, Opportunity, continues to study Victoria Crater, the half-mile-wide (800 meter) crater that has been its home for the past 6 months. Steve Squyres of Cornell University, principal investigator for the rovers, reported on their recent exploits Wednesday at the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston.

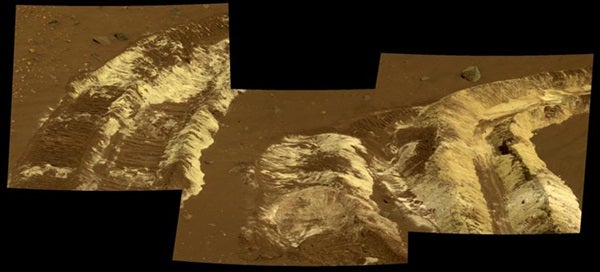

Although Spirit remained stationary, it didn’t shut down. Scientists used the time to take the best panorama of Mars they likely will ever get. The so-called McMurdo pan, named after the Antarctic explorer, is a full-color, high-resolution, 360° view of Spirit’s winter home. From its resting spot, Spirit also monitored the martian atmosphere. The rover spotted some high-altitude water-ice clouds — features not seen during its first winter. The discovery shows cloud formation varies from year to year on Mars.

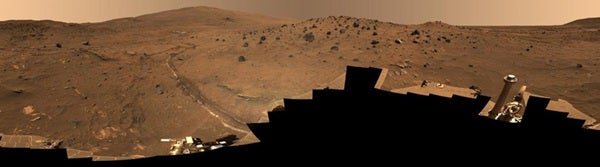

Halfway around Mars, Opportunity is getting a close-up look at Victoria Crater. The crater’s distinctive scalloped shape results from “mass wasting,” a process in which rocks and fine particles move rapidly downhill under gravity’s pull. Mass wasting creates the crater rim’s prominent alcoves, each separated by a sharp promontory. Most of the promontories expose several yards (meters) of layered bedrock on their nearly vertical faces. “Every promontory we’ve seen has the kinds of layering we expected for ancient wind-blown sand deposits,” says Squyres.

A dark debris apron about 0.3-mile wide (0.5 km) surrounds Victoria. This material was blasted from beneath the surface by the impact that formed the crater. The debris contains many large “blueberries” — hematite-rich spherules that probably formed in water. Opportunity found plenty of blueberries early in its mission, but they appeared to be absent from the wind-blown dust ripples just outside the ejecta pattern.

Opportunity now is traversing Victoria’s rim, and mission scientists are naming features they find after places visited by Ferdinand Magellan and his crew during the first circumnavigation of Earth. (Victoria Crater itself is named after the lone ship that completed Magellan’s quest.) Squyres and his team are committed to driving Opportunity into the crater eventually, if they’re sure the rover will be safe — in other words, that they can get it out again. Squyres is confident they can, and he thinks it will be sooner rather than later.