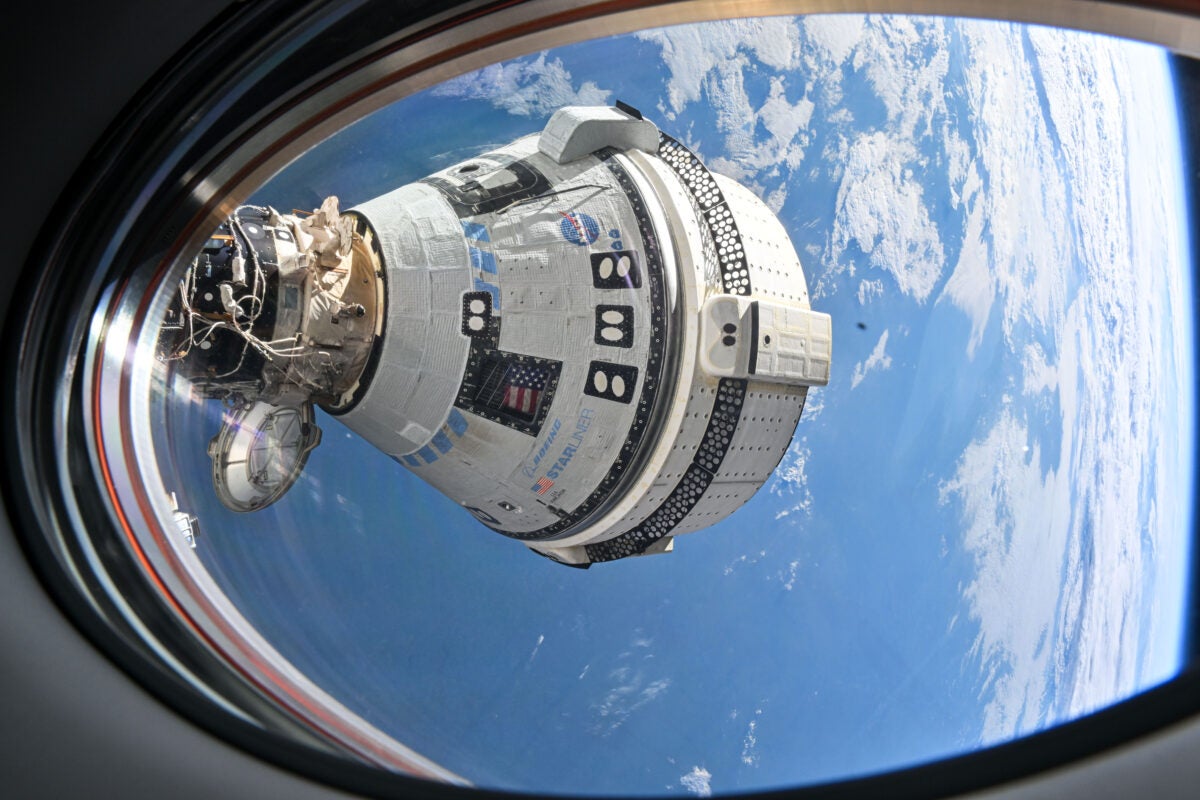

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft has been under the microscope after SpaceX stepped in to return NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams — who made the vehicle’s inaugural crew flight test (CFT) — from the International Space Station (ISS) after their sojourn was extended from about one week to more than nine months.

NASA on Thursday, though, said Starliner — which suffered helium leaks and degraded thrusters on orbit — could fly again as soon as this year. The timeline will depend upon the completion of testing at White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico, targeted for spring or summer.

“Once we get through these planned test campaigns, we will have a better idea of when we can go fly the next Boeing flight,” said Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, in an update. “We’ll continue to work through certification toward the end of this year and then go figure out where Starliner fits best in the schedule for the International Space Station and its crew and cargo missions.”

The space agency described the next flight as a “crew capable post-certification mission” but said it reserves the option to fly it as a cargo mission “depending on the needs of the agency.”

Officials last week said they were unsure if the mission would be crewed or uncrewed. But they insisted Boeing remains onboard with the program despite rumors that the firm is considering selling its space business.

“NASA is seeing the commitment from Boeing to adding the Starliner system to the nation’s crew transportation base,” Ken Bowersox, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations, said Thursday.

NASA and Boeing had planned for the CFT to be Starliner’s final test flight before it is certified to rotate astronaut crews at the ISS. The vehicle’s development is funded by $4.2 billion from Commercial Crew, of which SpaceX’s Crew Dragon — Wilmore and Williams’ ride home — is also a part. Dragon so far has flown all 10 Commercial Crew missions and is scheduled to launch an eleventh as soon as July. Boeing, meanwhile, has lost more than $2 billion on Starliner without completing an operational mission.

On Thursday, though, NASA said it is “making progress” toward certifying the vehicle for another crewed flight. In the months since Starliner’s uncrewed return, “more than 70 percent of flight observations and in-flight anomalies” have been closed at “program-level control boards,” the space agency said.

Personnel are working to solve the “in-flight anomalies” Starliner experienced: a series of helium leaks and faulty reaction control system (RCS) thrusters, which are designed to make precise orbital adjustments. Five of these thrusters failed to fire at full strength during the CFT.

Teams ultimately traced the latter issue to a design flaw in Starliner’s four doghouses: structures that each house seven RCS and five more powerful orbital maneuvering and control (OMAC) thrusters. Engineers believe the doghouses overheated, causing a seal to expand and block the flow of propellant.

“We thought, obviously, we had done enough analysis to show that the thrusters would be within the temperatures that they were qualified for,” Stich said in August. “Clearly, there were some misses in qualification.”

In the coming months, NASA will fire certain RCS thrusters on the ground at White Sands to “validate detailed thermal models and inform potential propulsion and spacecraft thermal protection system upgrades, as well as operational solutions for future flights.” The agency is considering installing new thermal barriers in the doghouses and changing the cadence of thruster firing to prevent overheating. It also said it is testing new seals for Starliner’s helium systems to prevent future leaks.

The investigation into the thruster issues, though, is “expected to remain open further into 2025, pending the outcome of various ground test campaigns and potential system upgrades.”

Stich last week said NASA has a “little bit more time” before it must decide whether Starliner will fly the Crew-12 mission. Commercial Crew missions typically span six months, and the agency on Thursday said Crew-11 would launch no earlier than July, which would put the Crew-12 launch around January.

NASA astronaut Mike Fincke, who was previously assigned to Starliner’s first operational mission, was announced as the Crew-11 pilot and will no longer fly on the Boeing spacecraft, the agency told FLYING.

A version of this story was first published on FLYING.