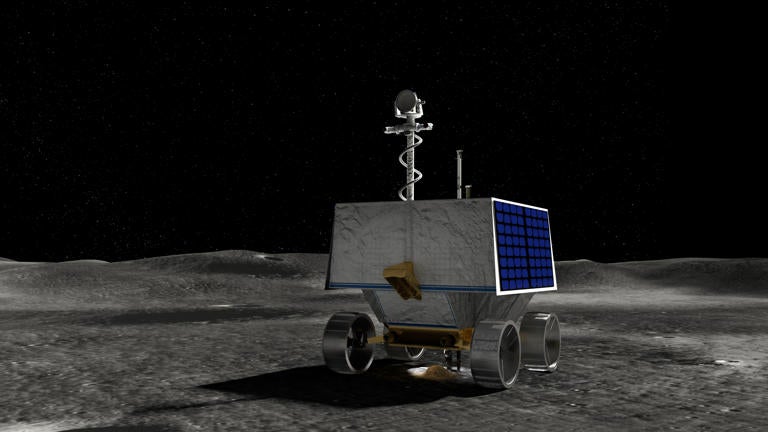

To the shock of the lunar science community, on July 17, NASA cancelled the much-anticipated Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) mission, which was expected to prospect for water ice on the Moon — a critical resource for future explorers.

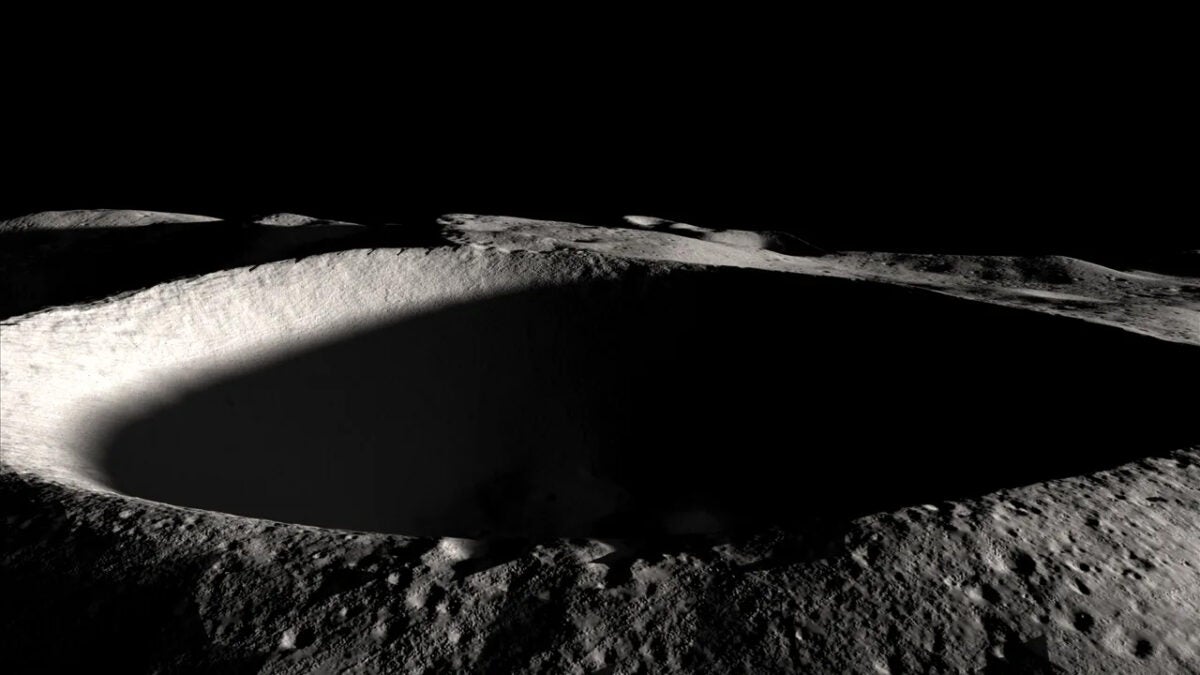

VIPER was one of the highest profile missions in NASA’s ongoing Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which is sending robotic missions to the Moon in support of future Artemis crews. Artemis targets landing near the lunar south pole, where the shallow angle of the Sun means many craters lie in permanent shadow. Scientists know that these craters contain water ice, which could be used as drinking water for astronauts and as a resource for rocket fuel and energy production. But we don’t know how much ice is there, nor how easy it will be to extract. VIPER’s mission was to answer those questions — and its cancellation deprives the Artemis program of critical data.

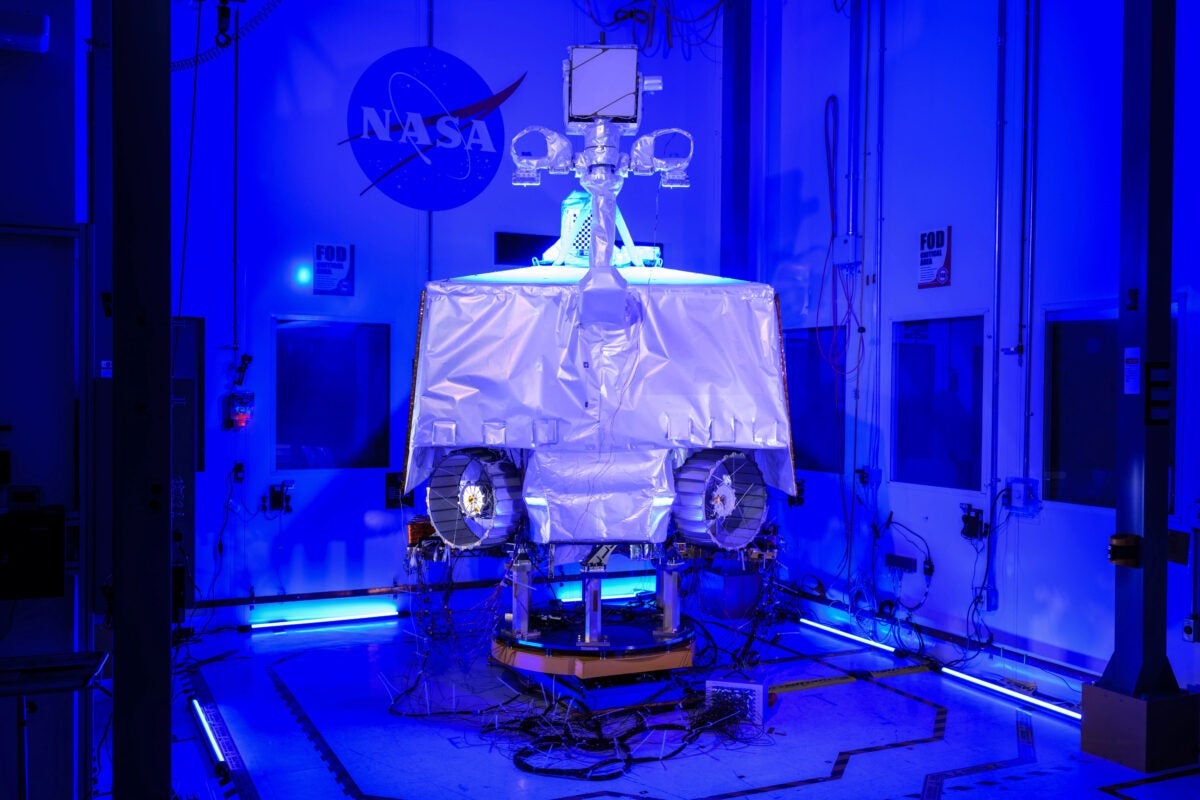

Equally shocking to the science community is that $450 million have already been spent designing and building VIPER and its suite of instruments. The completed VIPER only needed to pass its environmental tests, to ensure it could survive in the Moon’s incredibly harsh, perpetually shadowed polar regions. The rover, and the Astrobiotics Griffin lunar lander that was to deposit VIPER near the south pole, were scheduled to launch in September 2025, aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket.

NASA has said it is open to handing VIPER over to another organization to fly it to the Moon — if it comes at no additional cost to NASA. If no takers emerge, current plans call for the dismantling of VIPER and cannibalizing its instruments for possible use in future missions.

The cost of cost-cutting

NASA’s explanation for VIPER’s cancellation is that COVID-induced supply chain issues with both the rover and its Griffin lander escalated mission costs and have delayed its anticipated launch by two years. By cancelling the project, after already spending nearly half a billion dollars, NASA says it will save $84 million. At the same time, NASA will pay Astrobiotics $323 million to complete the Griffin lander and fly it to the Moon without VIPER. At this time, plans call for landing a “mass simulator,” or a dead weight, that will return no science data about the Moon.

An even deeper worry is that VIPER’s cancellation could be the tip of the iceberg for NASA’s ambitious, but chronically underfunded lunar exploration programs. VIPER’s demise is a clue that further bad news may lie ahead — not only with the robotic CLPS programs but the Artemis crewed return to the Moon. Landing a dead weight-laden Griffin lander that returns no lunar science data will certainly not help NASA’s funding issues.

In addition to the treasure trove of ice and volatiles data that will not be gathered, the cancellation is a public relations blow to NASA at a time when the agency needs public support. VIPER may not have gotten the same level of attention of flagship missions like Mars sample return or the James Webb Space Telescope, but videos of the rover skillfully maneuvering through test terrains continued to circulate on news feeds even several days after the program’s announced cancellation.

VIPER’s capabilities

Should VIPER ever get the chance to carry out its mission, it would bring to bear an array of features designed for exploring frosty, shaded polar craters. Standing a boxy five feet (1.5 meters) square and eight feet (2.4 m) high, the vehicle would have been the first on the Moon equipped with headlights for operating at night. VIPER also features an innovative wheel design, with independent steering and active suspension for all four wheels. This would allow the rover to traverse a variety of soil conditions on the Moon, ranging from compact beach-like sand to soft, fluffy dust that would stall a more conventional vehicle. To traverse particularly soft soil, VIPER’s wheels can be independently raised and swept fore and aft, propelling VIPER forward with a swimming motion.

VIPER’s prime objectives were to study the ices and volatiles in permanently shadowed polar craters so scientists could evaluate their usefulness for future crews. In addition to identifying useful volatiles like hydrogen, ammonia, and carbon dioxide, VIPER was to search for volatiles that could be harmful to the Artemis missions. To accomplish this, VIPER would have used a suite of spectrometers and a drill capable of penetrating the surface to a depth of 40 inches (1.0 m) to extract subsurface samples for analysis.

The Regolith and Ice Drill for Exploring New Territories (TRIDENT), developed by Honeybee Robotics, is a carbide-tipped percussion drill equipped with a temperature sensor on its tip. The drill would extract drill shavings that would be deposited in a chute for analysis by three spectrometers: the Neutron Spectrometer System (NSS), the Near Infrared Volatiles Spectrometer System (NIRVSS), and the Mass Spectrometer Observing Lunar Operations (MSolo).

Related: Scientists suspect there’s ice hiding on the Moon

Mission planning called for VIPER to operate for 100 days on the lunar surface. Controlled by a driver on Earth, the rover would be commanded to move in 15-foot (4.6 m) increments between science operations. The rover would have typically traversed terrain with up to a 15-degree slant but could have maneuvered on a 30-degree slope if needed. VIPER’s maximum speed would have been 0.45 mph (0.73 km/hr), or about 9 inches (23 centimeters) per second. This frantic pace would slow to 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 cm) per second during science operations when the spectrometers would analyze the surface for possible ice targets for the TRIDENT drill.

The Moon’s natural libration, or cyclical monthly nodding and rocking as seen from Earth, would periodically place the rover out of contact with mission controllers. Mission planning called for planned two-week traverses to explore for water, with the rover arriving at a predetermined location to await the reestablishment of line-of-sight communications with Earth. As the Sun never rises more than 10° above the horizon at VIPER’s landing site, the rover would need to be carefully positioned in order to ensure sunlight could reach its solar panels to recharge its batteries; VIPER can only survive 50 hours of continuous darkness.

VIPER’s Plan B

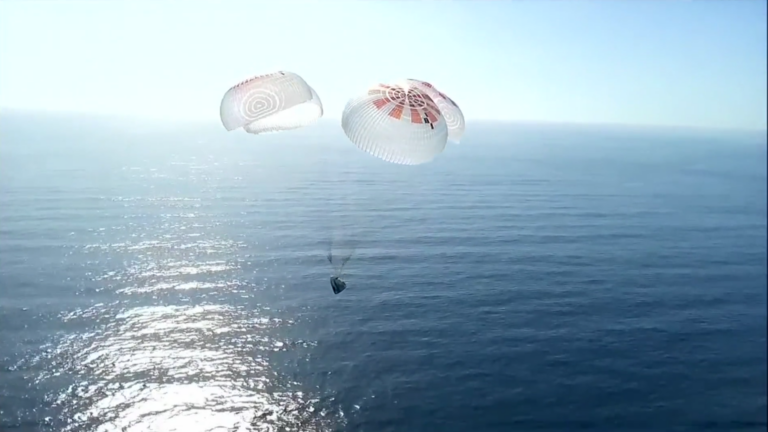

As exciting as the anticipated VIPER lunar ice data would have been, so far all is not lost. The Polar Resources and Ice Minning Experiment-1 (PRIME-1) mission is currently scheduled to launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 late this year and will also prospect for ice in the polar regions. PRIME-1 will carry identical copies of the TRIDENT lunar drill and MSolo spectrometer that were to operate on VIPER. However, these instruments will remain fixed to the PRIME-1 lander and will not be able to investigate extended areas as planned with the VIPER rover, significantly reducing their science output.