Key Takeaways:

NASA has set a goal to return rock and soil samples from the surface of Mars in the 2030s. The mission would represent the first time scientific samples from another planet have been returned to Earth. But the space agency said it needs another year to determine how to do it.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and Nicky Fox, associate administrator for the space agency’s Science Mission Directorate, on Tuesday said officials would not decide on a Mars Sample Return mission profile until mid-2026, at the earliest. The space agency will weigh two different options, or “landing architectures” — one that would use NASA-proven technology and another that would enlist commercial partners.

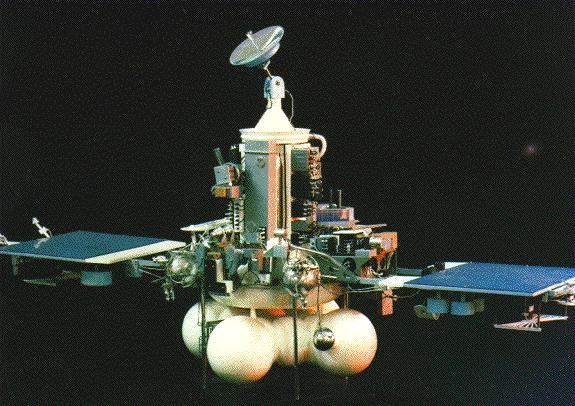

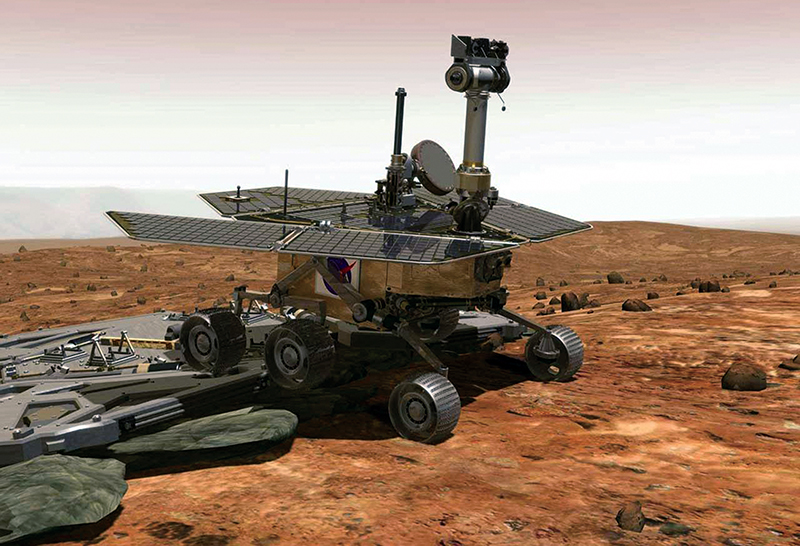

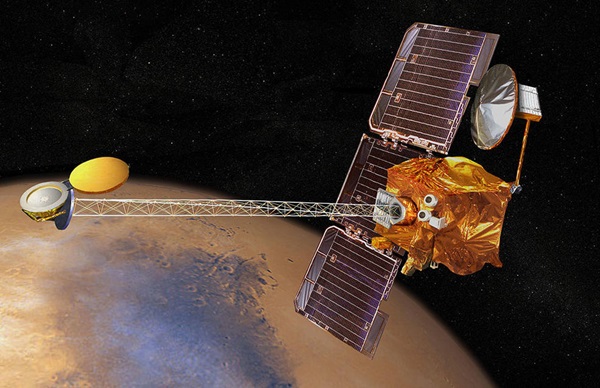

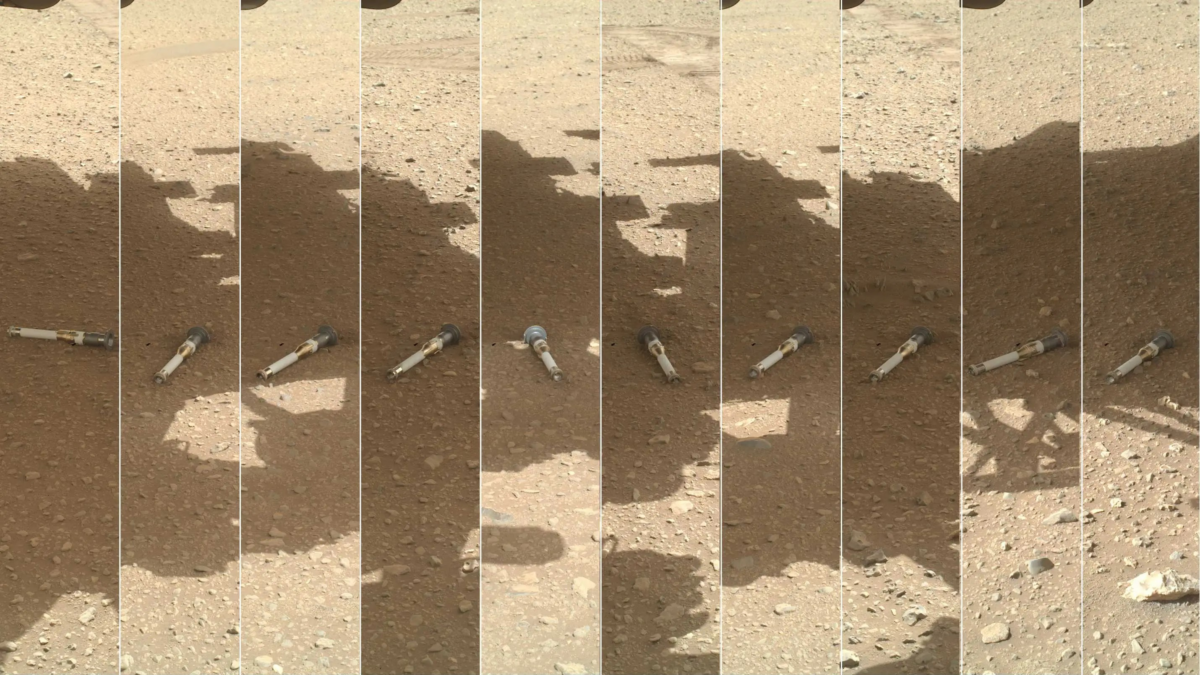

The Mars Sample Return program is a joint NASA and European Space Agency (ESA) initiative that so far has collected 28 titanium-sealed tubes containing cigar-sized samples dug up by NASA’s Perseverance rover from the lake bed of Mars’ Jezero Crater. The mission to return the samples is expected to make history with the first round-trip journey to and rocket launch from another planet, as well as the first time multiple spacecraft have landed on Mars at the same time.

“It’s humanity’s first mission to bring scientific samples from any planet right back here to Earth for study using our state of the art facilities,” said Fox. “They’ll not only help NASA prioritize which areas of the Red Planet might be the most fruitful for our future astronaut led research, but they’ll also lead to more incredible scientific discoveries about what Earth was like before life, as well as what life might have been like on Mars — and indeed, what it could look like in the future.”

NASA in April sent a plea for help with Mars Sample Return, which according to a 2023 Independent Review Board analysis is more than $6 billion over budget. The report predicted it would not return Martian samples until the 2040s, a timeline Nelson on Tuesday called “unacceptable.”

The agency’s request returned 11 studies from the NASA community and space industry. Ultimately, NASA settled on two options, with the key difference being the way a Mars sample retrieval lander is delivered to the planet’s surface.

Option 1 is the sky crane method, which NASA previously used to land Perseverance and another rover, Curiosity, on Mars. Both vehicles are about the size of a car and needed extra power to land.

Similarly, Mars Sample Return requires the delivery of a landing platform containing a lander and Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) — the rocket that will lift the samples into Mars orbit — to the planet. The sky crane would deploy a parachute and small rocket boosters to slow itself down before depositing the landing platform on the surface using a cable. Fox said the vehicle must be about 20 percent larger than the one that landed Perseverance.

At the same time, NASA will gauge what its commercial partners can do.

“Option 2 is looking at the possibility of going into commercial capabilities: a heavy lander with existing commercial partners,” Nelson said.

The NASA administrator mentioned SpaceX and Blue Origin, two of NASA’s largest contractors, but said a team will evaluate all options. According to Fox, a commercial lander would not be able to directly deposit a landing platform on the surface like Sky Crane.

Both mission profiles would require a redesigned landing platform that will carry a lander and a smaller version of the MAV previously planned for the mission. The platform’s sample loading system will be upgraded to brush dust off of sample containers, and its solar panels will be replaced by radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs).

“That may sound like we’re making it more complicated, but actually that provides power and heat through the dust storm season on Mars,” said Fox. “That actually allows us to reduce complexity, and it … allows us to bring back the samples earlier.”

According to Nelson, the Sky Crane option would cost between $6.6 billion and $7.7 billion — a “far cry” from the previously projected $11 billion. The commercial option would cost between $5.8 billion and $7.1 billion.

“Either of these two options are creating a much more simplified, faster and less expensive version than the original plan,” said Nelson.

The agency believes the new options could return Martian samples as early as 2035 or as late as 2039. In the end, Nelson said, it will come down to what the incoming administration does with NASA’s fiscal year 2025 budget. And he made a request: at least $300 million for the Mars Sample Return program.

“The bottom line of $300 million is what the Congress ought to consider,” said Nelson. “And if they want to get this thing back on a direct return earlier, they’re going to have to put more money into it, even more than $300 million in fiscal year 2025. And that would be the case every year going forward.”

According to Fox, with the updated mission options, the earliest launch date for ESA’s Earth Return Orbiter — which will snatch the samples out of Mars orbit and fly them back to Earth — is 2030. The sample return lander could launch the following year, she said.

But NASA engineers will need at least one more year to weigh the options.

“Whichever path we go forward with,” Fox said, “there is work to be done to get us to a point where we can say, ‘Yes, this is the mission we’re going to go forward with. This is when we confirm the budget. This is when we confirm the schedule.’”

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on Flying.