In recent years, it’s been operating with just one instrument, as the other two succumbed to the elements and ceased functioning. Despite its diminished capacity, the telescope is still delivering ground-breaking science. Now, NASA has finally decided to shut down the aging telescope. It will be switched off January 30, 2020.

That the telescope has lasted this long is a testament to the engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who have adapted with the telescope’s age to keep it functioning as best they could.

A Long Life

As with other infrared telescopes, Spitzer is sensitive to heat. Even the tiny amount of heat generated by its own electronics, and the glare of sunlight as it orbits, can create noise in its images. That’s why the telescope was designed to fly far from Earth’s own warmth, and reflect sunlight back without absorbing any more energy than it needs to power itself.

It also carried coolant to keep its instrumentation chilled, though it needed less than previous telescopes due to its clever design and orbit. Still, that coolant ran out back in 2009, rendering two of its instruments useless. Since then, it’s been running in what engineers call “warm mode,” with only two of the original four light wavelength windows available on its remaining instrument.

Due to its distant, Earth-trailing orbit, Spitzer has also drifted farther from Earth over time. It’s now about 600 times the Earth-Moon distance from us, and the angles between Spitzer, Earth, and the sun have shifted since the mission’s start. That makes sending data back to Earth a problem.

The telescope can’t charge its solar panels and communicate with Earth at the same time due to a geometric mismatch between its solar and communication arrays, and it only has so much battery life. So it can only point to Earth for 2.5 hours at a time before it must turn back to the sun and recharge. And that window will only grow shorter as the spacecraft continues to drift farther behind Earth.

On top of the time limitation, the angle Spitzer must turn to talk to Earth at all these days is beyond its original limits. Engineers have had to turn off certain safety protocols to tilt the spacecraft toward Earth as the angle between them has changed. If the spacecraft were to put itself in safe mode, engineers worry it might never emerge, thanks to aging systems and the increasing difficulty of communicating with the spacecraft.

Spitzer’s Rich Legacy

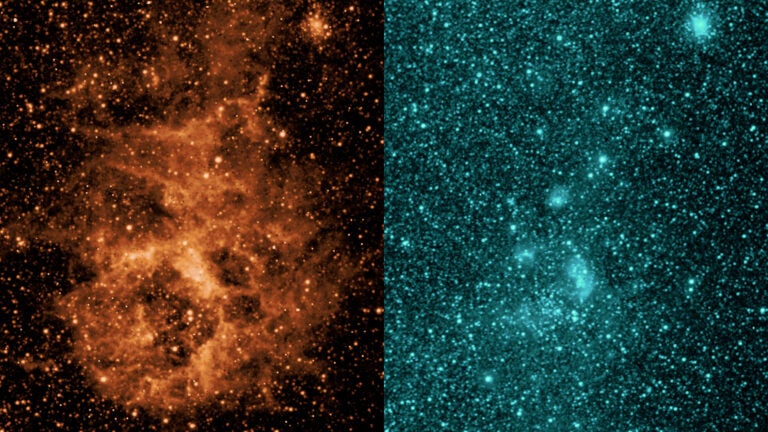

In its time, Spitzer was one of NASA’s premiere space telescopes, classified among the space agency’s “Great Observatories” alongside Hubble, Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory. Spitzer revealed breathtaking views of otherwise invisible materials swirling through the cosmos. It captured galaxies from the early days of the universe, their light shifted and stretched over the eons from bright ultraviolet light then to a dimmer infrared glow now. For nearer galaxies, Spitzer has helped pinpoint where rich dust lanes lay, and where star formation is churning out piles of baby stars.

Spitzer was also the first telescope to directly detect an exoplanet, picking up the light from HD 209458b in 2005. Until then, every exoplanet detection had been indirect, based on the wobble or transit of the star.

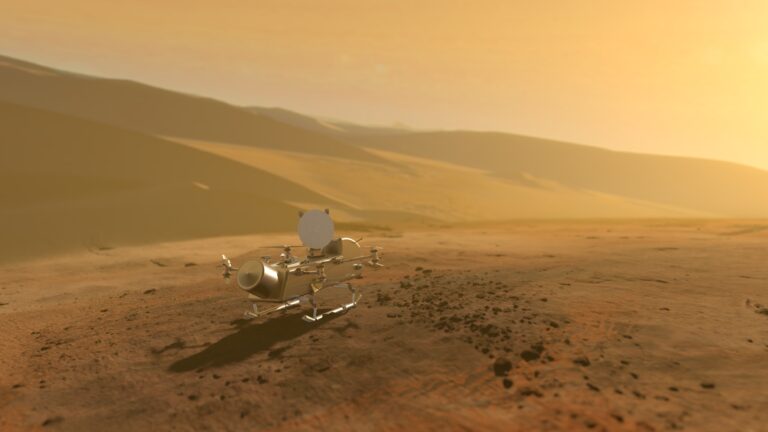

While generally considered a successor to Hubble, the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope is mostly an infrared instrument, and will pick up where Spitzer leaves off. With a primary mirror 7.5 times larger than Spitzer’s, JWST will see the universe though much of the same light, but with far greater precision.

“There have been times when the Spitzer mission could have ended in a way we didn’t plan for,” said Bolinda Kahr, Spitzer’s mission manager, in a press release. “I’m glad that in January we’ll be able to retire the spacecraft deliberately, the way we want to do it.”