On Tuesday morning, NASA will test the launch abort safety system for Orion. The event will last only about three minutes, but it will be a major milestone in clearing Orion to safely transport humans to space. The launch window opens at 7 a.m. EDT, and current weather predictions give an 80 percent chance for clear launch conditions.

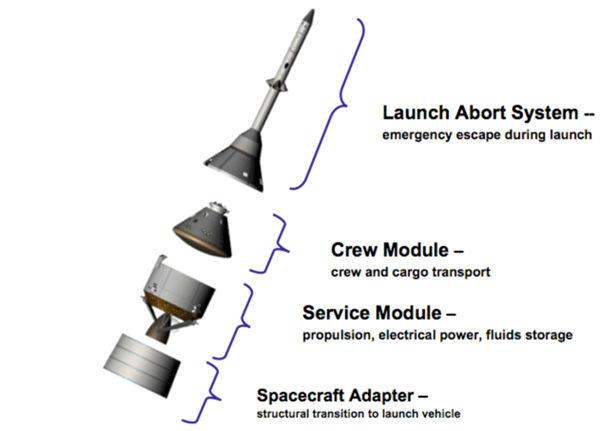

The launch abort system (LAS) is essentially another rocket mounted to the front of the crew capsule. It’s meant to pull the crew capsule safely away from the main rocket booster and all its explosive power if something goes wrong during launch. The capsule, equipped with parachutes, could then float safely to the ground.

While the LAS system has been improved over the years, some version of this escape system has been in use since the days of Mercury and Apollo. Because Orion is meant to ride on SLS, the most powerful rocket yet built, Orion’s LAS must be able to pull away even faster than in previous missions. If it passes this test – which does not include any crew – then the next time the LAS will fly will be during Artemis-2, the mission that will fly humans into space on Orion for the first time.

Short Test, Big Consequences

While some variation of the LAS has existed since the start of the space program, it thankfully hasn’t seen much use in flight. But the Russian version was put to the test just last October when a Soyuz rocket malfunctioned on its way to the International Space Station. Working just as it should, the launch abort system automatically jettisoned the crew capsule, containing cosmonaut Alexey Ovchinin and astronaut Nick Hague, away from the malfunctioning booster.

The test machine that will fly tomorrow contains four main parts. The first is the crew module itself. For Tuesday’s test, this won’t be a true Orion crew capsule, since engineers plan to let it crash into the ocean at high speed, where it will almost certainly break apart and sink. The real crew capsule will have parachutes to safely deliver astronauts back to the ground. This is just a mockup with the same weight and shape as Orion.

The crew module is connected at the bottom to a ring that simulates where the service module would attach, and at the top to the tower that includes the actual abort system engines. The tower also includes a cover that provides heat shielding to the crew capsule if the LAS is actually put to use.

But for the test tomorrow, and anytime something goes wrong, the LAS will instead take the crew capsule with it, pulling away from the main booster with roughly 400,000 pounds of thrust and then flipping around to make sure the heat shield is aimed down. This move also subjects anything or anyone inside the capsule to 7g’s of force – that’s seven times normal Earth gravity.

NASA astronaut Randy Bresnik spoke at a pre-launch briefing on Monday at Cape Canaveral. He pointed out that astronauts typically experience about 5g’s of force during a normal Soyuz re-entry, and that’s after usually weeks or months of zero-gravity in space. 7g’s should be manageable for astronauts leaving from Earth, he says. For the Soyuz re-entry, Bresnik likened the feeling to “an elephant standing on your chest. For LAS, it’s more like one and a half or two elephants.”

But again, for tomorrow’s test, there will be no parachutes, and the capsule will likely hit the water at some 300 miles per hour. NASA will be keeping tabs on the capsule the whole time by radio, logging data at every step of the test. But just in case something goes wrong with transmission, the capsule will also jettison data recorders as it falls back to Earth. The recorders are equipped with beacons and further labeled with NASA’s logo and an email address and phone number, in case someone other than NASA picks them up.

If all goes well, Orion’s next big tests will happen at the end of the month, when the real crew capsule and service module are put together. They will fly on a plane to Sandusky, Ohio, where the two modules will undergo testing to ensure they can withstand the stresses of launch and re-entry.

The first uncrewed launch of Orion is currently slated for next year, with the crewed version – including the full launch abort system – set to launch in 2023.

Tomorrow’s launch will stream live on NASA’s website, with coverage starting at 6:40 a.m. EDT.