Twin NASA spacecraft have provided scientists with their first view of the speed, trajectory, and three-dimensional shape of powerful explosions from the Sun known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs). This new capability will dramatically enhance scientists’ ability to predict if and how these solar tsunamis affect Earth.

When directed toward our planet, these ejections can be breathtakingly beautiful and yet potentially cause damaging effects worldwide. The brightly colored phenomena known as aurorae — more commonly called Northern or Southern Lights — are examples of Earth’s upper atmosphere harmlessly being disturbed by a CME. However, ejections can produce a form of solar cosmic rays that can be hazardous to spacecraft, astronauts, and technology on Earth.

Space weather produces disturbances in electromagnetic fields on Earth that can induce extreme currents in wires, disrupting power lines, and causing widespread blackouts. These Sun storms can interfere with communications between ground controllers and satellites and with airplane pilots flying near Earth’s poles. Radio noise from the storm also can disrupt cell-phone service. Space weather has been recognized as causing problems with new technology since the invention of the telegraph in the 19th century.

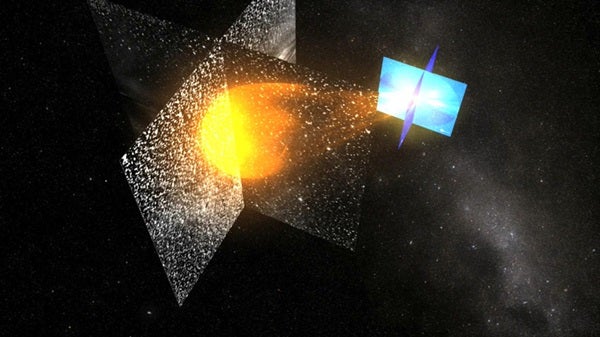

NASA’s twin Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft are providing the unique scientific tool to study these ejections as never before. Launched in October 2006, STEREO’s nearly identical observatories can make simultaneous observations of these ejections of plasma and magnetic energy that originate from the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. The spacecraft are stationed at different vantage points. One leads Earth in its orbit around the Sun, while the other trails the planet.

Using three-dimensional observations, solar physicists can examine a CME’s structure, velocity, mass, and direction in the corona while tracking it through interplanetary space. These measurements can help determine when a CME will reach Earth and predict how much energy it will deliver to our magnetosphere, which is Earth’s protective magnetic shield.

“Before this unique mission, measurements and the subsequent data of a CME observed near the Sun had to wait until the ejections arrived at Earth 3 to 7 days later,” said Angelos Vourlidas, a solar physicist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington. Vourlidas is a project scientist for the Sun Earth Connection Coronal and Heliospheric Investigation, STEREO’s key science instrument suite. “Now we can see a CME from the time it leaves the solar surface until it reaches Earth, and we can reconstruct the event in 3D directly from the images.”

These ejections carry billions of tons of plasma into space at thousands of miles per hour. This plasma carries some of the magnetic field from the corona and can create a large, moving disturbance in space that produces a shock wave. The wave can accelerate some of the surrounding particles to high energies that can produce a form of solar cosmic rays. This process also can create disruptive space weather during and following the CME’s interaction with Earth’s magnetosphere and upper atmosphere.

Angelos Vourlidas, SECCHI project scientist, talks about coronal mass ejections-explosions of the Sun’s atmosphere that propagate in space in the form of a cloud, and how the STEREO satellites are helping scientists reconstruct a three-dimensional view of their structures. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center