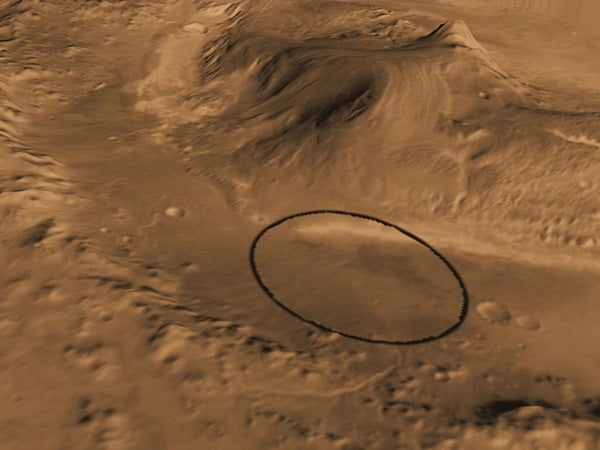

The car-sized Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), Curiosity, is scheduled to launch late this year and land in August 2012. The target crater spans 96 miles (154 kilometers) in diameter and holds a mountain rising higher from the crater floor than Mount Rainier rises above Seattle, Washington. Gale is about the combined area of Connecticut and Rhode Island. Layering in the mound suggests it is the surviving remnant of an extensive sequence of deposits. The crater is named for Australian astronomer Walter F. Gale.

“Mars is firmly in our sights,” said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden. “Curiosity not only will return a wealth of important science data, but it will serve as a precursor mission for human exploration to the Red Planet.”

During a prime mission lasting 1 martian year — nearly 2 Earth years — researchers will use the rover’s tools to study whether the landing region had favorable environmental conditions for supporting microbial life and for preserving clues about whether life ever existed.

“Scientists identified Gale as their top choice to pursue the ambitious goals of this new rover mission,” said Jim Green from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “The site offers a visually dramatic landscape and also great potential for significant science findings.”

In 2006, more than 100 scientists began to consider about 30 potential landing sites during worldwide workshops. Four candidates were selected in 2008. An abundance of targeted images enabled thorough analysis of the safety concerns and scientific attractions of each site. A team of senior NASA science officials then conducted a detailed review and unanimously agreed to move forward with the MSL Science Team’s recommendation. The team is composed of a host of principal and co-investigators on the project.

Curiosity is about twice as long and more than 5 times as heavy as any previous Mars rover. Its 10 science instruments include two for ingesting and analyzing samples of powdered rock that the rover’s robotic arm collects. A radioisotope power source will provide heat and electric power to the rover. A rocket-powered sky crane suspending Curiosity on tethers will lower the rover directly to the martian surface.

The portion of the crater where Curiosity will land has an alluvial fan likely formed by water-carried sediments. The layers at the base of the mountain contain clays and sulfates, both known to form in water.

“One fascination with Gale is that it’s a huge crater sitting in a low-elevation position on Mars, and we all know that water runs downhill,” said John Grotzinger from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “In terms of the total vertical profile exposed and the low elevation, Gale offers attractions similar to Mars’ famous Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the solar system.”

Curiosity will go beyond the “follow-the-water” strategy of recent Mars exploration. The rover’s science payload can identify other ingredients of life, such as the carbon-based building blocks of biology called organic compounds. Long-term preservation of organic compounds requires special conditions. Certain minerals, including some Curiosity may find in the clay and sulfate-rich layers near the bottom of Gale’s mountain, are good at latching onto organic compounds and protecting them from oxidation.

“Gale gives us attractive possibilities for finding organics, but that is still a long shot,” said Michael Meyer from NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at agency headquarters. “What adds to Gale’s appeal is that, organics or not, the site holds a diversity of features and layers for investigating changing environmental conditions, some of which could inform a broader understanding of habitability on ancient Mars.”

The car-sized Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), Curiosity, is scheduled to launch late this year and land in August 2012. The target crater spans 96 miles (154 kilometers) in diameter and holds a mountain rising higher from the crater floor than Mount Rainier rises above Seattle, Washington. Gale is about the combined area of Connecticut and Rhode Island. Layering in the mound suggests it is the surviving remnant of an extensive sequence of deposits. The crater is named for Australian astronomer Walter F. Gale.

“Mars is firmly in our sights,” said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden. “Curiosity not only will return a wealth of important science data, but it will serve as a precursor mission for human exploration to the Red Planet.”

During a prime mission lasting 1 martian year — nearly 2 Earth years — researchers will use the rover’s tools to study whether the landing region had favorable environmental conditions for supporting microbial life and for preserving clues about whether life ever existed.

“Scientists identified Gale as their top choice to pursue the ambitious goals of this new rover mission,” said Jim Green from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “The site offers a visually dramatic landscape and also great potential for significant science findings.”

In 2006, more than 100 scientists began to consider about 30 potential landing sites during worldwide workshops. Four candidates were selected in 2008. An abundance of targeted images enabled thorough analysis of the safety concerns and scientific attractions of each site. A team of senior NASA science officials then conducted a detailed review and unanimously agreed to move forward with the MSL Science Team’s recommendation. The team is composed of a host of principal and co-investigators on the project.

Curiosity is about twice as long and more than 5 times as heavy as any previous Mars rover. Its 10 science instruments include two for ingesting and analyzing samples of powdered rock that the rover’s robotic arm collects. A radioisotope power source will provide heat and electric power to the rover. A rocket-powered sky crane suspending Curiosity on tethers will lower the rover directly to the martian surface.

The portion of the crater where Curiosity will land has an alluvial fan likely formed by water-carried sediments. The layers at the base of the mountain contain clays and sulfates, both known to form in water.

“One fascination with Gale is that it’s a huge crater sitting in a low-elevation position on Mars, and we all know that water runs downhill,” said John Grotzinger from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “In terms of the total vertical profile exposed and the low elevation, Gale offers attractions similar to Mars’ famous Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the solar system.”

Curiosity will go beyond the “follow-the-water” strategy of recent Mars exploration. The rover’s science payload can identify other ingredients of life, such as the carbon-based building blocks of biology called organic compounds. Long-term preservation of organic compounds requires special conditions. Certain minerals, including some Curiosity may find in the clay and sulfate-rich layers near the bottom of Gale’s mountain, are good at latching onto organic compounds and protecting them from oxidation.

“Gale gives us attractive possibilities for finding organics, but that is still a long shot,” said Michael Meyer from NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at agency headquarters. “What adds to Gale’s appeal is that, organics or not, the site holds a diversity of features and layers for investigating changing environmental conditions, some of which could inform a broader understanding of habitability on ancient Mars.”