Named Gravity Recovery And Interior Laboratory (GRAIL), the spacecraft are scheduled to be placed in orbit beginning at 4:21 p.m. EST for GRAIL-A on December 31 and 5:05 p.m. EST for GRAIL-B the next day.

“Our team may not get to partake in a traditional New Year’s celebration, but I expect seeing our two spacecraft safely in lunar orbit should give us all the excitement and feeling of euphoria anyone in this line of work would ever need,” said David Lehman from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

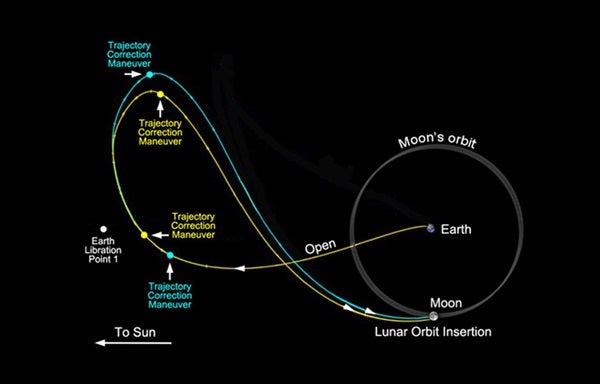

The distance from Earth to the Moon is approximately 250,000 miles (400,000 kilometers). NASA’s Apollo crews took about three days to travel to the Moon. Launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station September 10, 2011, the GRAIL spacecraft are taking about 30 times that long and covering more than 2.5 million miles (4 million km) to get there.

This low-energy, long-duration trajectory has given mission planners and controllers more time to assess the spacecraft’s health. The path also allowed a vital component of the spacecraft’s single science instrument, the Ultra Stable Oscillator, to be continuously powered for several months. That let it reach a stable operating temperature long before science measurements from lunar orbit are to begin.

“This mission will rewrite the textbooks on the evolution of the Moon,” said Maria Zuber from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “Our two spacecraft are operating so well during their journey that we have performed a full test of our science instrument and confirmed the performance required to meet our science objectives.”

As of December 28, GRAIL-A was 65,860 miles (106,000 km) from the Moon and closing in at a speed of 745 mph (1,200 km/h). GRAIL-B was 79,540 miles (128,000 km) from the Moon and closing in at a speed of 763 mph (1,228 km/h).

During their final approaches to the Moon, both orbiters will move toward it from the south, flying nearly directly over the lunar south pole.

The lunar orbit insertion burn for GRAIL-A will take approximately 40 minutes and change the spacecraft’s velocity by about 427 mph (688 km/h). GRAIL-B’s insertion burn 25 hours later will last about 39 minutes and is expected to change the probe’s velocity by 430 mph (691 km/h).

The insertion maneuvers will place each orbiter into a near-polar elliptical orbit with a period of 11.5 hours. Over the following weeks, the GRAIL team will execute a series of burns with each spacecraft to reduce their orbital period from 11.5 hours down to about two hours. At the start of the science phase in March 2012, the two GRAILs will be in a near-polar, near-circular orbit with an altitude of about 34 miles (55 km).

When science collection begins, the spacecraft will transmit radio signals precisely defining the distance between them as they orbit the Moon. As they fly over areas of greater and lesser gravity, caused both by visible features such as mountains and craters and by masses hidden beneath the lunar surface, they will move slightly toward and away from each other. An instrument aboard each spacecraft will measure the changes in their relative velocity precisely, and scientists will translate this information into a high-resolution map of the Moon’s gravitational field. The data will allow mission scientists to understand what goes on below the surface. This information will increase our knowledge of how Earth and its rocky neighbors in the inner solar system developed into the diverse worlds we see today.

Named Gravity Recovery And Interior Laboratory (GRAIL), the spacecraft are scheduled to be placed in orbit beginning at 4:21 p.m. EST for GRAIL-A on December 31 and 5:05 p.m. EST for GRAIL-B the next day.

“Our team may not get to partake in a traditional New Year’s celebration, but I expect seeing our two spacecraft safely in lunar orbit should give us all the excitement and feeling of euphoria anyone in this line of work would ever need,” said David Lehman from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

The distance from Earth to the Moon is approximately 250,000 miles (400,000 kilometers). NASA’s Apollo crews took about three days to travel to the Moon. Launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station September 10, 2011, the GRAIL spacecraft are taking about 30 times that long and covering more than 2.5 million miles (4 million km) to get there.

This low-energy, long-duration trajectory has given mission planners and controllers more time to assess the spacecraft’s health. The path also allowed a vital component of the spacecraft’s single science instrument, the Ultra Stable Oscillator, to be continuously powered for several months. That let it reach a stable operating temperature long before science measurements from lunar orbit are to begin.

“This mission will rewrite the textbooks on the evolution of the Moon,” said Maria Zuber from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “Our two spacecraft are operating so well during their journey that we have performed a full test of our science instrument and confirmed the performance required to meet our science objectives.”

As of December 28, GRAIL-A was 65,860 miles (106,000 km) from the Moon and closing in at a speed of 745 mph (1,200 km/h). GRAIL-B was 79,540 miles (128,000 km) from the Moon and closing in at a speed of 763 mph (1,228 km/h).

During their final approaches to the Moon, both orbiters will move toward it from the south, flying nearly directly over the lunar south pole.

The lunar orbit insertion burn for GRAIL-A will take approximately 40 minutes and change the spacecraft’s velocity by about 427 mph (688 km/h). GRAIL-B’s insertion burn 25 hours later will last about 39 minutes and is expected to change the probe’s velocity by 430 mph (691 km/h).

The insertion maneuvers will place each orbiter into a near-polar elliptical orbit with a period of 11.5 hours. Over the following weeks, the GRAIL team will execute a series of burns with each spacecraft to reduce their orbital period from 11.5 hours down to about two hours. At the start of the science phase in March 2012, the two GRAILs will be in a near-polar, near-circular orbit with an altitude of about 34 miles (55 km).

When science collection begins, the spacecraft will transmit radio signals precisely defining the distance between them as they orbit the Moon. As they fly over areas of greater and lesser gravity, caused both by visible features such as mountains and craters and by masses hidden beneath the lunar surface, they will move slightly toward and away from each other. An instrument aboard each spacecraft will measure the changes in their relative velocity precisely, and scientists will translate this information into a high-resolution map of the Moon’s gravitational field. The data will allow mission scientists to understand what goes on below the surface. This information will increase our knowledge of how Earth and its rocky neighbors in the inner solar system developed into the diverse worlds we see today.