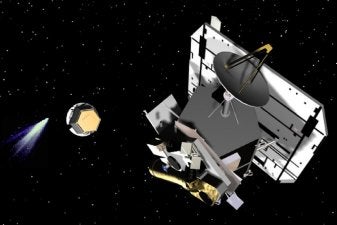

NASA has given a team of scientists from the University of Maryland the green light to fly the Deep Impact spacecraft to Comet Hartley 2 on a two-part extended mission know as EPOXI. The spacecraft will fly by Earth on New Year’s Eve at the beginning of a more than two-and-a-half-year journey to Hartley 2.

The EPOXI mission is actually two new missions in one. During the first 6 months of the journey to Hartley 2, the Extrasolar Planet Observations and Characterization (EPOCh) mission will use the larger of the two telescopes on the Deep Impact spacecraft to search for Earth-sized planets around five stars selected as likely candidates for such planets. Upon arriving at the comet, the Deep Impact Extended Investigation (DIXI) will conduct an extended flyby of Hartley 2 using all three of the spacecraft’s instruments, two telescopes with digital color cameras and an infrared spectrometer.

“It’s exciting that we can send the Deep Impact spacecraft on a new mission that combines two totally independent science investigations, both of which can help us better understand how solar systems form and evolve,” says Deep Impact leader and University of Maryland astronomer Michael A’Hearn, principal investigator for both the overall EPOXI mission and its DIXI component.

On July 4th 2005, Deep Impact made history and worldwide headlines when it smashed a probe into Comet Tempel. The mission yielded a wealth of new cometary information, but the data on Tempel 1 was, in many cases, startlingly different of that from comet missions Deep Space 1 and Stardust. As a result, rather than revealing the true nature of comets, the sometimes conflicting data from these three missions has left scientists questioning most of what they thought they knew about these fascinating, and potentially dangerous, objects; and longing for new data from other comets.

“One of the great surprises of comet explorations has been the wide diversity among the different cometary surfaces imaged to date,” says A’Hearn. “We want a close look at Hartley 2 to see if the surprises of Tempel 1 are more common than we thought, or if Tempel 1 really is unusual.”

After the completion of Deep Impact, the mission team knew they had a still healthy and flight-proven spacecraft that was capable of traveling to a never-before-visited comet at a fraction of the cost of a newly built and launched mission. In 2006 the team began the proposal process that eventually became EPOXI.

When the Deep Impact/EPOXI spacecraft passes by Earth on December 31, 2007, it will use the pull of our planet’s gravity to direct and speed itself toward Comet Hartley 2. In doing this, the spacecraft is aimed toward an encounter with Comet Hartley 2 at a time when tracking stations in two different locations on Earth can “see” the spacecraft to receive data from it and send commands to it. In late December 2007, the spacecraft’s instruments will be recalibrated using the Moon as a target.

Hartley 2 was not the original destination of the new mission. It was selected in October following the surprising realization that despite tremendous efforts by many observatories and observers, the scientists could not reliably identify their first choice, Comet Boethin, and its orbit in time to plan the mission flyby of Earth. The team then recommended to NASA that it be allowed to fly to the backup target, Comet Hartley 2.

“Hartley 2 is scientifically just as interesting as Comet Boethin since both have relatively small, active nuclei,” says A’Hearn. “As we have worked the details of the Comet Hartley 2 encounter, we are confident that the observations will turn out to be even better than Boethin.”

The first part of the Deep Impact extended mission, the search for alien worlds, will begin in late January as the spacecraft cruises toward Hartley 2. More than 200 alien (extrasolar) planets have been discovered to date. Most of these are detected indirectly, by the gravitational pull they exert on their parent star. Directly observing extrasolar planets by detecting the light reflected from them is very difficult, because a star’s brilliance obscures light coming from any planets orbiting it.

However, sometimes the orbit of an extrasolar world is aligned so that it eclipses its star as seen from Earth. In these rare cases, light from that planet can be seen directly.

“When the planet appears next to its star, your telescope captures their combined light. When the planet passes behind its star, your telescope only sees light from the star. By subtracting light from just the star from the combined light, you are left with light from the planet,” says Goddard scientist Drake Deming, who heads EPOCh and is deputy principal investigator for EPOXI. “We can analyze this light to discover what the atmospheres of these planets are like.”

Planets as small as three Earth masses can be detected in this way. EPOCh will also observe the Earth in visible and infrared wavelengths to allow comparisons with future discoveries of Earth-like planets around other stars.

The mission will observe five nearby stars with “transiting extrasolar planets,” so named because the planet transits, or passes in front of, its star. The planets were discovered earlier and are giant planets with massive atmospheres, like Jupiter in our solar system. They orbit their stars much closer than Earth does the Sun, so they are hot and belong to the class of extrasolar planets nicknamed “Hot Jupiters.”

However, these giant planets may not be alone. If there are other worlds around these stars, they might also transit the star and be discovered by the spacecraft. Even if they don’t transit, Deep Impact could find them indirectly. Their gravity will pull on the transit planets, altering their orbits and the timing of their transits.

“Since Deep Impact will be able to stare at these stars for long periods, we can observe multiple transits and compare the timing to see if there are any hidden worlds,” says Deming.

In June of 2008, the extended mission will end its EPOCh portion and transition to a long, quiet journey to Comet Hartley 2. The total trip, measured from its December 31, 2007 flyby of Earth to its closest encounter with the comet on October 11, 2010, will be roughly 1.6 billion miles or some 18 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. It will take the spacecraft three trips around the Sun before it can intercept the comet, which at that time will be at a distance of some 12.4 million miles from Earth.

At the nearest point of its flyby of Hartley 2, the spacecraft will be some 550 miles from the comet. Deep Impact does not have another probe, so Hartley 2 will not get hit, but the close-up view will allow the spacecraft’s two telescopes to closely observe surface features of the comet while its infrared spectrometer maps the composition of any outbursts of gas from the surface.