I had come to Caltech fresh from graduate school to take a postdoctoral position that paid $22,000 a year. With over half of that destined for rent, the numbers added up to “poor,” but we convinced ourselves we wouldn’t be there for long. I’d spend a year helping get ready for the launch of our space telescope, then a year or two getting some science done. From there, it would hopefully be on to the closest thing to immortality academia has to offer — the track to tenure.

Five months later, the world watched in disbelief when Challenger exploded shortly after launch.

It was over four years before Discovery finally carried the Large Space Telescope, newly renamed Hubble, into orbit. A lot had happened in the meantime, but on that morning in April 1990, it was “attaboys” all around.

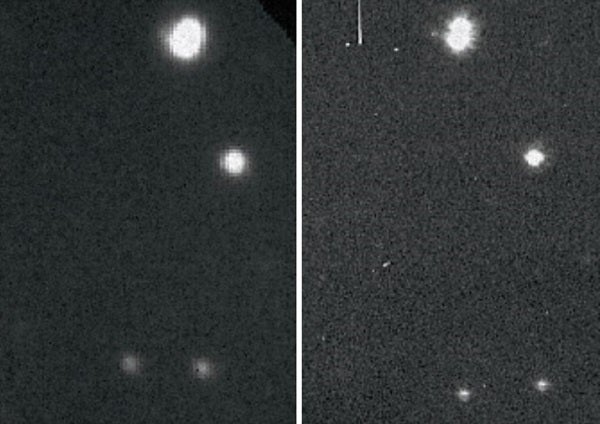

The thing is, all it takes to topple a huge pile of “attaboys” is a single “aw s—.” So it was a month later as Bob Light and I sat at computer screens in front of NASA Select television cameras, staring in confusion at the very first image from Hubble. Jim Westphal, the principal investigator on the Wide Field and Planetary Camera, was standing behind us talking to the cameras.

The script had called for a quick show. The Hubble image would be spectacular in comparison to a groundbased image of the same field. Glasses would be raised in triumphant toast and those of us fortunate to be in the right place at the right time would ride off into a sunset filled with wonder. But to quote the poet Robert Burns, “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men …” The newly launched miracle of science and engineering had the most basic, no-one-could-ever-miss-it problem a telescope mirror could have.

Lots of people independently recognized what was going on, but on my personal timeline, the first was Roger Lynds. Roger was known as a bit of an eccentric. At WFPC team meetings, Roger tended to walk around rather than sit, and you could always tell when he was thinking because he would rub his bald head. The more agitated he was about something, the more vigorous the self-administered cranial massage. After the debacle of first light, Roger was staring at the screen and polishing his crown with wild abandon. Then he made a pronouncement.

“Damned thing’s got spherical aberration!”

It would turn out that the $3 billion problem with Hubble came down to a submillimeter paint chip that nobody bothered to look for because they needed an answer right now. Rushing the process is rarely a good idea.

Most readers probably look back on 1990 as the nowseldom-discussed prelude to Hubble’s phoenixlike rise from the ashes. Hubble went on to deliver on all of its original promise and more. But in the moment, lacking a crystal ball, astronomers greeted the news by throwing themselves off of observatory catwalks, figuratively if not literally.

I was part of Hubble’s ultimate triumph as well. Maybe I’ll return to it in three years with the 30th anniversary of the first Servicing Mission. But for now, hopefully this handful of words will offer the reader some small glimpse into what it felt like to a young postdoc who had hitched his wagon to a wild and uncertain horse.

There’s also a cautionary tale hiding in this bit of admittedly romanticized remembrance. If the space biz taught me anything, it is that worldshaking events are usually the ones you should have seen coming, but didn’t. Forgetting that physics doesn’t give a rodent’s posterior about schedule, budget, or politics is an invitation for Murphy’s law to come out and play.

Now, with Hubble nearing the end of its life, it’s the James Webb Space Telescope proclaiming, “Damn the torpedoes and full speed ahead!” Having blown through its original $1 billion price tag and 2007 launch date, some “lovingly” refer to the $10 billion Webb as “The Telescope That Ate Astronomy.” A friend who works on the project recently confided in me about what he sees as “big scaries,” but went on to say that so much is riding on Webb’s success that “it is unthinkable that it won’t work.”

I shudder at that. Orbiting at L2, this time there will be no do-overs. I have tremendous respect for the people working on Webb, but physics can be a perverse comedian, and “it has to work” is probably its favorite straight line.

Oh well. You pays yer money and you takes yer chances. For now, I vicariously share the excitement of the young astronomers who are waiting and hoping for a ride like the one I was privileged to take. Fingers crossed!