As Moscow’s clocks tick past midnight to welcome Wednesday, June 5, the world heralds a new hero: a man who already is a national icon in Russia and his homeland Turkmenistan. Six decades after Yuri Gagarin first conquered space, Oleg Kononenko — a quiet, unassuming mechanical engineer, avid reader, and volleyball player — becomes the first person to log 1,000 days off planet Earth.

“I sometimes go back in time and analyze the steps and actions I took,” he once said in an interview. “And I realize that the vector was always pointed towards space.”

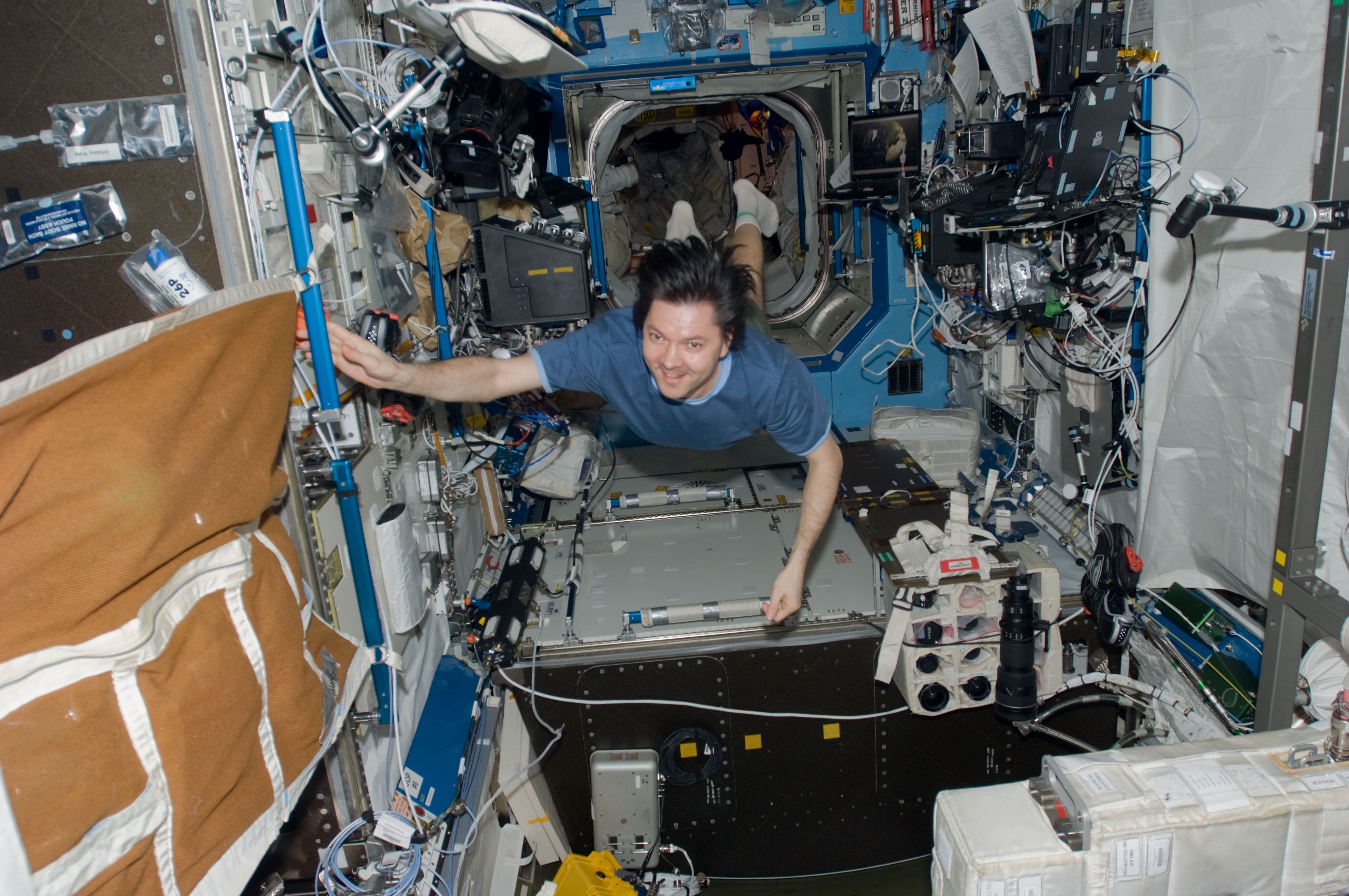

Spread over 16 years and five International Space Station (ISS) expeditions, Kononenko’s feat equates to 33 months, or 1.6 percent of his life — he was born in June 1964. He’s orbited Earth 16,000 times and flown 420 million miles (675 million kilometers) — enough “space mileage” for hundreds of round trips to the Moon, a voyage to Mars, or even a one-way ticket to Jupiter.

Kononenko’s “kilo-versary” places humanity in ample stead to explore deep space. Since April 2008, he’s shared the ISS with 55 individuals from 13 nations, including the first astronauts from South Korea, Denmark, Türkiye, and Belarus. He flew twice with Gennady Padalka, the Russian cosmonaut who first held the world record for the longest space-time with 878 days — which Kononenko broke February 4 of this year.

A little background on Oleg Kononenko

Kononenko had a highly eventful career as a mechanical engineer with an aviation specialty and as a cosmonaut since 1996. He had a full home life as well, a husband to Tatyana Mikhailovna Kononenko and a father to two children. His family understood his dedication and passion when he commanded four Soyuz missions, spent three Christmases and New Years in orbit, and celebrated four off-planet birthdays. They continue supporting him as he completes a monumental milestone not only for himself but for humanity.

Humanity’s adventure in space began with several cosmonauts. After Gagarin’s 108-minute, single-orbit flight in April 1961, Gherman Titov spent a day in space in August 1961, Andriyan Nikolayev logged nearly four days (94 hours) in August 1962 and Valery Bykovsky’s five days in June 1963 remains the longest solo mission in history.

Three years later the United States took the lead in space exploration. In August 1965, Gemini 5’s Gordon Cooper and Charles “Pete” Conrad flew a week-long endurance mission to test whether a lunar mission was possible — which they wryly dubbed “8 Days or Bust.”

The nearly eight-day record fell to Gemini 7’s crewmembers Frank Borman and Jim Lovell in December 1965. Their 14-day mission — grimy, cramped, and decidedly unglamorous — proved that humans could survive a round-trip flight to the Moon. Afterward, Lovell flew three more times, accruing 29 days in space by 1970; he was Earth’s most experienced astronaut from 1966 to 1973.

Meanwhile, in June 1970 cosmonauts Nikolayev and Vitali Sevastyanov smashed Gemini 7’s record with a 17-day orbital stay on Soyuz 9. A year later, Georgi Dobrovolski, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev spent 23 days aboard the Salyut 1 (the world’s first space station) but tragically died when a malfunction led to premature depressurization of their Soyuz 11 capsule during re-entry.

The competition heats up

In June 1973, Conrad eclipsed Lovell’s record aboard NASA’s Skylab — America’s first space station — amassing a 49-day career total throughout his four missions. In September of that same year, Alan Bean advanced the lead to 69 days. And Gerald “Jerry” Carr, Edward Gibson, and William Pogue finished Skylab’s last mission, Skylab 4, in February 1974 after 84 days.

The advantage then returned — and remained — with Russian endurance missions. Six flights to their Salyut 6 space station passed 96 days in March 1978 (Soyuz 26), 139 days in November 1978 (Soyuz 29), 175 days in August 1979 (Soyuz 32), and 184 days by October 1980 (Soyuz 35).

Salyut 7 facilitated new records of 211 days in December 1982 with its first crew arriving on the Soyuz T5, and of 237 days when Leonid Kizim, Vladimir Soloviev, and Olef Atkov ended their space mission on Oct. 2, 1984.A few years later, Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov spent a continuous year from December 1987 to December 1988 (365 days, 22 hours) off Earth on the Soviet space station Mir.

But humanity’s longest-ever mission was volunteered for and flown by a physician, Valeri Polyakov. Initially planned for 18 months from November 1993 to May 1995, a combination of launch delays, technical woes, and schedule conflicts truncated it to 16 months, then 14 months. It eventually launched in January 1994, where Polyakov flew 437 days, 17 hours and 58 minutes, circled Earth 6,927 times, and traveled 183 million miles (295 million kilometers).

Despite a decline in his mood early in the flight, Polyakov’s blues stabilized and he exhibited no cognitive or performance shortfalls. He returned home in March 1995 and walked unaided from the Soyuz capsule to prove that humans could one day work on Mars after a multi-month weightless transit to the red planet.

Female astronauts just want to have fun

Today, women represent 12 percent of all astronauts, but of course, this number was nearly non-existent just 60 years ago. Russia’s Valentina Tereshkova, a factory worker picked by Soviet propagandists to cynically one-up the United States, was the first female space traveler. However, despite her headline-breaking mission of nearly three days and completing 48 orbits in June 1963, two decades elapsed before another woman followed in her footsteps.

The second female astronaut was Svetlana Savitskaya, whose flights to Salyut 7 in August 1982 and July 1984 made her the first female to fly twice, walk in space, and perform an extravehicular activity, and pushed her space-time tally to 19 days. On the other hand, America had a larger corps of women astronauts and quickly utilized its numerical advantage. By November 1993, Shannon Lucid amassed 34 space-days, longer than any woman at the time.

Dovetailed into the latter half of Polyakov’s mission, the first long-term female cosmonaut arrived aboard Mir. In October 1994, Yelena Kondakova boarded Mir and when she returned home 169 days later with Polyakov, they set two empirical records: Polyakov for the longest spaceflight by a man and Kondakova for the longest spaceflight by a woman.

But while Polyakov’s record still stands, Kondakova’s fell in September 1996 when Lucid wrapped up a 188-day Mir stay and a career spanning 223 days. Her achievement lasted more than a decade. In June 2007, Sunita Williams broke Lucid’s single-flight record on a 194-day ISS mission. And in November 2007, Peggy Whitson eclipsed Lucid’s total, returning home in April 2008 after 376 days — the first woman to accrue a year in space.

Collecting time in space

Back in August 1980, after Leonid Popov and Valeri Ryumin spent 184 days in space, Ryumin took it a step further and extended the record for most logged space-time by a male space traveler with 371 days over four missions (two short-term and two long-term).

Aboard the Mir space station in July 1986, Kizim became the first person to surpass a full year (374 days) throughout his career. And Yuri Romanenko’s 326-day mission on Soyuz TM-2 allowed him to accrue 400 days in November 1987; whiling away the quiet hours on Mir by playing guitar and singing salubrious love songs. And in April 1991, during another Mir stay, Manarov passed 500 days in space (a total of 541 days) for the first time.

In September 2017, Whitson completed another ISS mission, lasting 9½ months. During that epic voyage, she passed 400 cumulative days in space in December 2016, then 500 in March 2017 and 600 in June 2017. She also commanded a privately financed AxiomSpace mission in May 2023, pushing her personal tally to 675 days (22 months), with over 10,500 orbits and 283 million miles (455 million kilometers) flown.

Despite having twice as much space-time as any other woman, one of Whitson’s records fell in February 2020 when Christina Koch finished a 328-day ISS stay, the longest-ever spaceflight by a female. Koch flew 5,200 orbits and 139 million miles (223 million kilometers). “Records are meant to be broken,” Whitson wrote in a congratulatory note to Koch. “It’s a sign of progress.”

Russia’s Sergei Avdeyev first accrued 700 days in July 1997, then Sergei Krikalev exceeded 800 days in October 2005. Now, Oleg Kononenko has passed 900 days this past February on the 26th. He will reach 1,000 days on Wednesday, June 5th. By the time he returns home on 24 September, he will amass 1,111 days — over 17,300 orbits and 466 million miles (750 million kilometers) — across his stellar career.

To explore the solar system and someday lay human footprints on the Moon and Mars demands more than just longevity. Knowledge from Kononenko’s career will furnish new insights into keeping astronauts healthy, mitigating radiation hazards, and understanding how humans function under conditions of extreme isolation and profound stress.

And Kononenko is certainly a man with an eye on what comes next. “I am a person who does not analyze the past,” he said. “I live in the present. And a little bit in the future.”