On January 4, 2004, NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover Spirit tore into the thin martian atmosphere and came safely to rest on the flat plain of Gusev Crater. One Earth year later, both Spirit and its twin, Opportunity (which landed on Meridiani Planum January 25), are still exploring the Red Planet — “in great shape for their age,” according to Jim Erickson, the rovers’ project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

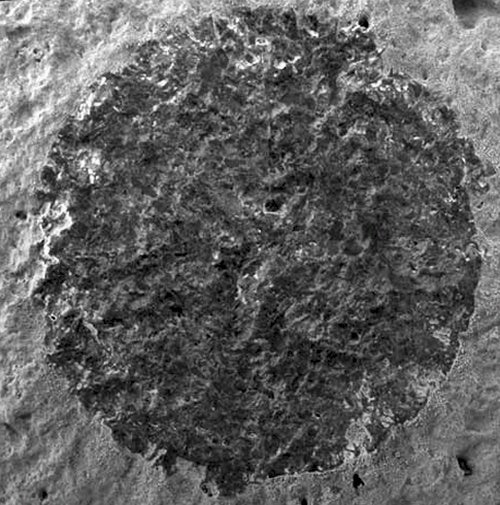

At a JPL ceremony commemorating the anniversary of the landings, rover project scientist Steve Squyres of Cornell University announced Spirit has found a rock, dubbed Wishstone, in the Columbia Hills with an unusual texture and chemistry.

“The weird stuff, though,” Squyres says, “is when you look at the chemistry.” Wishstone proved highly enriched in the element phosphorus when compared to the rocks of Gusev’s plains and even the rocks seen elsewhere in the Columbia Hills. “This rock is chock-full of phosphorus,” says Squyres.

Where did it come from? Squyres won’t rule out the idea that the grains came from a phosphate-rich rock broken up by the violent event. But “the other possibility is that this is a phosphate deposited from water.” If that’s what happened, he says, “it speaks of a water chemistry dramatically different from what we saw just 500 meters [a quarter-mile] away” on the West Spur of the Hills. He adds that another phosphate-rich rock, dubbed Champagne, has been found: “As we look at a family of these rocks, we’ll be able to test hypotheses for how they formed.”

Mission scientists are driving Spirit up to the crest of Cumberland Ridge to a spot called Larry’s Lookout, where they hope to look down into a valley on the eastern side of the Hills and perhaps spot bedrock. Where Spirit goes after that will depend on what it finds.

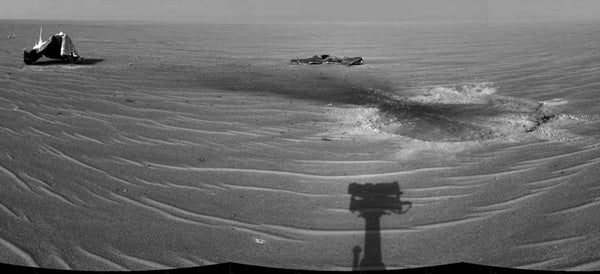

On the other side of Mars, Opportunity is examining the remains of the heat shield that protected it during entry. Engineers are hoping to study the debris to refine heat-shield designs for future missions.

As to what lies ahead for Opportunity, Squyres says the next objective is Vostok, a circular feature about 70 yards in diameter. It lies about 0.75 mile (1.2 kilometers) south of the heat shield, on the way toward enigmatic features scientists call the Etched Terrain.

Vostok’s nature isn’t clear, Squyres explains. “It’s sort of crater-like in appearance, but it’s funny looking.” On the way, Squyres says, Opportunity will visit several small craters, both as navigation checkpoints and to see what they show of the local rock layers.

After Vostok, Squyres says, “we going to head south toward the Etched Terrain — and more discoveries.”