“Planck has been a wonderful mission; spacecraft and instruments have been performing outstandingly well, creating a treasure-trove of scientific data for us to work with,” said Jan Tauber from ESA.

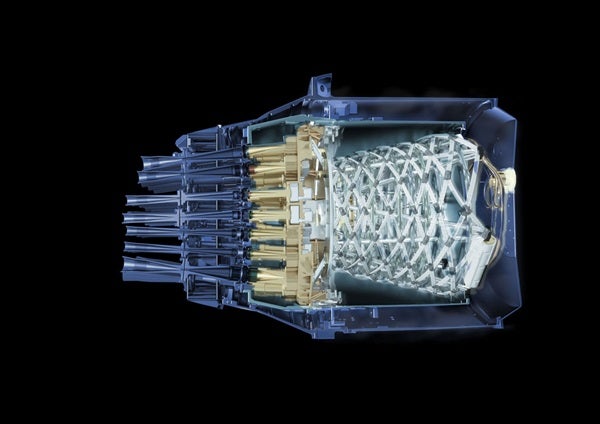

Less than half a million years after the universe was created in the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago, the fireball cooled to temperatures of about 7200° Fahrenheit (4000° Celsius), filling the sky with bright, visible light. As the universe has expanded, that light has faded and moved to microwave wavelengths. By studying patterns imprinted in that light today, scientists hope to understand the Big Bang and the very early universe, long before galaxies and stars first formed. Plank has been measuring these patterns by surveying the whole sky with its HFI and its Low Frequency Instrument (LFI). Combined, they give Plank unparalleled wavelength coverage and the ability to resolve faint details.

Launched in May 2009, the minimum requirement for success was for the spacecraft to complete two whole surveys of the sky.

In the end, Planck worked perfectly for 30 months, about twice the span originally required, and completed five full-sky surveys with both instruments. “This gives us even better data than we were expecting from the mission,” said Jean-Loup Puget from the Université Paris Sud, Orsay, France.

Able to work at slightly higher temperatures than HFI, the LFI will continue surveying the sky for a large part of 2012, providing calibration data to improve the quality of the final results.

Planck sees not only the primordial microwaves from the Big Bang, but also the emission from cold dust throughout the universe.

Initial results from Planck were announced last year. These include a catalog of galaxy clusters in the distant universe, many of which had not been seen before and included some gigantic “superclusters” — probably merging clusters.

Another highlight from the initial results was the best measurement yet of an infrared background covering the sky, produced by stars forming in the early universe. This showed how some of the first galaxies were producing a thousand times more stars every year than our galaxy does today.

More results from Planck will be announced next month, but the first results on the Big Bang and very early universe will not come for another year. Extremely careful and painstaking analysis of the data is needed to remove all of the contaminating foreground emission and tease out the faintest, most subtle signals in the remnant emission.

The results are widely anticipated because, despite two previous space missions to map this emission, there are still many competing ideas about what happened during the Big Bang.

“Planck’s data will kill off whole families of models; we just don’t know which ones yet,” said Puget.

The Big Bang data will be released in two stages, the first 15.5 months’ worth in early 2013, and then the full data release from the entire mission a year after that.

“We’re very pleased with how Planck has performed, well beyond expectations,” said Alvaro Giménez from ESA. “In reality though, we’re only halfway through the mission: There’s a lot still to be done to analyze the data and come up with the exciting scientific results that everyone’s anxiously expecting.”