Last week’s passing of Frank Borman, who led humanity’s first circumnavigation of the Moon, reduces the surviving number of Apollo lunar voyagers to eight.

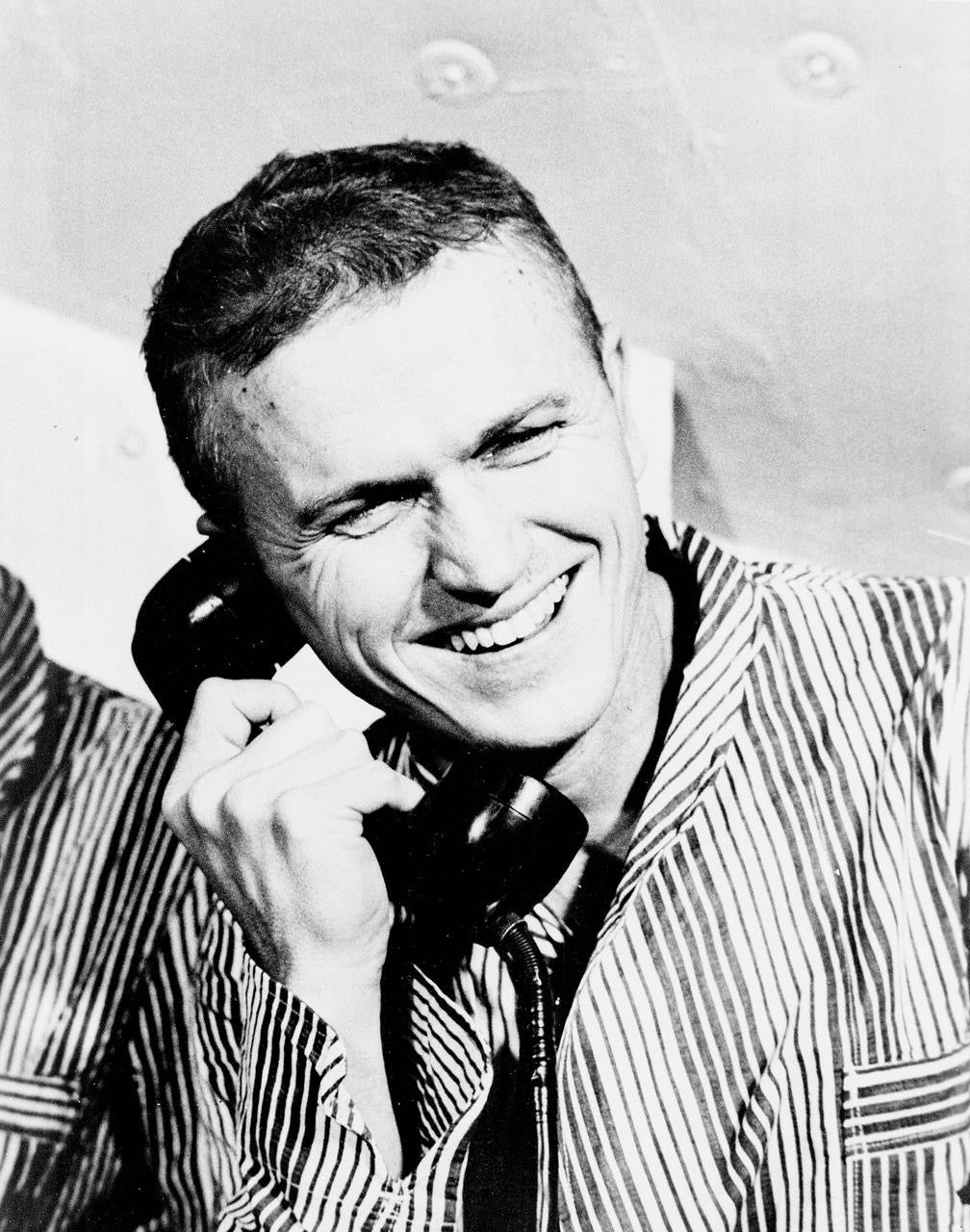

Aged 95, Borman was the oldest living space traveler, an uncomplicated military man of grit, tenacity and unswerving devotion to the mantra of duty, honor and country espoused by his beloved West Point.

Nicknamed “Squarehead” at school, “an unflattering reference to the general contours of my cranial structure,” Borman wrote, this unwanted epithet returned to haunt him decades later, atop towering Tucson billboards. Welcome Home, Squarehead, they crowed, as this stern, chisel-jawed Air Force fighter pilot paraded his boyhood hometown as Arizona’s first astronaut.

Frank Frederick Borman II, a descendent of Hanoverian immigrants from Germany, was born in Gary, Indiana, on March 14, 1928, the son of an automobile mechanic father and a mother who traced her roots to the well-heeled English town of Bath. Borman’s sinus problems led his parents to uproot from Indiana’s cool, damp climate and relocate westward.

In the “unspoiled, spacious beauty” of Arizona’s second city, the boy shined. Inheriting from Edwin and Marjorie Borman a steely work ethic and love of the outdoors, often bringing home toads, gophers, a Gila monster and — to his father’s horror — a huge tarantula.

That yearning for adventure was overwhelmed, aged five, by aviation, when Edwin took his son on a barnstorming ride in a decrepit World War I biplane. “I was captivated,” Borman wrote, “by the feel of the wind and the sense of freedom that flight creates so magically.”

Each Sunday, he flew rubber-band-propelled model airplanes. At 15, with cash earned sweeping shop floors, bagging groceries and pumping gas, he took flying lessons. A lifelong love affair with the sky was born.

Another love affair bloomed with Susan Bugbee, a “blond, beautiful and brainy” surgeon’s daughter. Married in 1950, they had two sons, Fred and Edwin.

Borman entered the Military Academy at West Point, graduating eighth in his class, then joined the Air Force. After serving as an instructor pilot, he earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from Caltech, then held an assistant professorship in thermodynamics and fluid mechanics at West Point. He completed test pilot school alongside future astronauts Mike Collins and Jim Irwin.

Frank Borman joined NASA in 1962

Selected in September 1962 into NASA’s second astronaut class — the “new nine,” whose roster included Neil Armstrong and Ed White — his 3,600 hours in jets set him apart from his peers. Chief Astronaut Deke Slayton felt the decisive, no-nonsense Borman “was tenacious enough” for long-duration spaceflight. After backing up Gemini 4 in June 1965, he was appointed to command Gemini 7 with Jim Lovell as his pilot.

Their flight sought to prove that men could survive two weeks in space, the time needed to travel to the Moon and back. But Gemini 7 changed direction when misfortune hit a preceding mission. Gemini 6 astronauts Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford were to rendezvous with an unmanned Agena target vehicle. But the Agena exploded shortly after liftoff in October 1965, eliminating their rendezvous target and scratching their mission.

Plans were formulated to fly Borman and Lovell in December as Gemini 6’s new target, the first time two U.S. manned spacecraft flew together. An early plan called for the pilots to spacewalk from ship to ship: Stafford returning home with Borman on Gemini 7, Lovell with Schirra on Gemini 6.

But Borman, possessed of an unshakable focus on the mission, regarded such capers with disdain. A spacewalk might make headlines, he opined, “but one little slip could lose the farm.”

Gemini 7 rose from Pad 19 at Florida’s Cape Kennedy at 2:30 P.M. EST on December 4, 1965, its Titan II rocket inserting Borman and Lovell into a 186-mile (300 kilometers) orbit. They performed 20 experiments, executed station-keeping tests with the Titan’s second stage and wore comfortable ‘soft’ space suits. They even sang Top 40 hits to pass the time.

But comfort proved a scarce commodity. Cabin temperatures grew insufferably warm and they endured stuffy noses and burning eyes. Then, a urine bag burst in Borman’s hand.

“Before or after?” asked flight surgeon Chuck Berry.

“After,” replied a dejected Borman.

Berry winced. “Sorry about that, chief.”

But the rendezvous with Gemini 6 proved the mission’s high-watermark. On December 15, Schirra and Stafford approached within 130 feet (40 meters) of Gemini 7 — and came as near as 1 foot (30 centimeters) at one point — to station-keep for five hours and three orbits. Air Force diehard Borman proudly displayed a “Beat Army” card at his window to taunt naval aviator Schirra.

206 orbits of Earth

Gemini 7 splashed down in the Atlantic at 9:05 A.M. EST on December 18 after 13 days, 18 hours, 35 minutes, and 206 orbits. It remained the longest human spaceflight until June 1970 and America’s longest non-space station mission for a quarter-century, finally overtaken by space shuttle Columbia in July 1992.

Borman was next named to Apollo 3, testing the Command and Service Module (CSM) and Lunar Module (LM) in a highly elliptical orbit, voyaging to an altitude of 4,000 miles (6,400 km), farther from Earth than ever before. Borman, Mike Collins and Bill Anders should have flown the mighty Saturn V rocket in fall 1967. But with appalling suddenness, tragedy struck.

On January 27, 1967, Apollo 1 astronauts Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee died when a flash fire swept through their spacecraft during a ground test. Borman, usually a teetotaler, admitted that he “went out and got bombed” after the disaster. “We ended up throwing glasses,” he said, “like a scene out of an old World War I movie.”

More trouble lay ahead. Collins was grounded by a spinal problem and his place on the crew was taken by Jim Lovell. Meanwhile, CIA reports hinted that Russia was planning a manned lunar flyby. In August 1968, NASA tapped Borman’s mission (now renamed Apollo 8) to fly 240,000 miles (370,000 km) to the Moon and back.

It was an audacious plan, but one that NASA hoped would bring President John F. Kennedy’s pledge of American boots on the lunar surface before the decade’s end tantalizingly closer.

Borman, Lovell and Anders departed Cape Kennedy’s Pad 39A at 7:51 A.M. EST on Dec. 21, 1968. Riding the 363-foot-tall (111 m) Saturn V, the most powerful rocket ever built, they left planet Earth under 7.7 million pounds (3.5 million kilograms) of thrust, with an explosive equivalent “about equal,” Borman said, “to a small atom bomb.”

Three hours later, the Saturn V’s S-IVB third stage ignited for the Translunar Injection (TLI) burn to set Apollo 8 on course for the Moon. It accelerated the spacecraft to over 23,000 miles (37,000 km) per hour to escape Earth’s gravitational influence. The three men were traveling faster than any humans ever before.

Despite a bout of space sickness suffered by Borman, the outbound journey was uneventful and early on Christmas Eve, Apollo 8 slipped silently into a circular orbit just 69 miles (110 km) above the Moon’s ubiquitous grey surface. During 10 orbits over 20 hours, they witnessed the first “Earthrise” from lunar distance and read from the Biblical story of Creation to a spellbound world.

First Anders, then Lovell, intoned the verses as the home planet hung like a blue-and-white marble in the ethereal blackness. Then Borman closed with: “Good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you… all of you on the good Earth.”

Returning to Earth and a Pacific Ocean splashdown on December 27 triggered a bout of seasickness in Borman. Lovell and Anders showed no mercy. “What do you expect,” they teased, “from a West Point ground-pounder?”

That ground-pounder later joined Eastern Airlines, rising to become chairman of the board. In retirement, Borman purchased a cattle ranch in Montana’s Bighorn Mountains and after John Glenn’s death in December 2016 was the oldest living space traveler, a title now held by Jim Lovell.

Yet even in later life, Borman regarded the Moon with awestruck wonder. “I can’t believe I was really there,” he told NASA’s Oral History Project. “But most often, I find I just revel in the beautiful Moon.”

And Borman’s name, figuratively and literally, remains there. In the deep south of the Moon’s farside, within an impact feature named Apollo, lies a 30-mile-wide (50 km) crater. Sharp-edged, with a rough, generally flat interior, the crater bears the name Borman, honoring a man who led our first faltering steps out of Earth’s protective embrace and into the universe around us.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Gemini 7 made 206 orbits of the Moon.