In November 2022, a Chinese Long March 5B rocket reentered the atmosphere with no ability to control where it fell. As a precaution, France, Spain, and Monaco closed some of their airspace along the booster’s possible path.

As it happened, the rocket reentered over the Pacific Ocean, not Europe. But the airspace closures still resulted in 645 planes being delayed by an average of nearly half an hour. The unexpected diversions also led to congestion in the skies above nations who chose not to close their airspace.

Although the impacts were relatively minor, the risk of occurrences like it continue to grow as both space and air traffic increase. And while the odds of an out-of-control rocket colliding with an aircraft are low, the outcome could be catastrophic.

In a study published in Scientific Reports on Jan. 23, Ewan Wright, a doctoral student at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and his colleagues calculated the likelihood of space debris from rocket launches falling into crowded airspace, which could cause delays or even crashes and casualties.

Is the sky falling?

Wright and his colleagues focused on reentering rocket bodies. Despite the growing trend of reusable boosters pioneered by SpaceX, most rockets still use expendable stages that fall back to Earth immediately after they have lofted their payloads. And many upper rocket stages are abandoned in orbit and could reenter at a later date. (As of March 2025, over 2,000 rocket bodies are still in Earth orbit, according to the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office.)

RELATED: What is space junk and why is it a problem?

While some space objects burn up completely in the atmosphere, because of their large size, rocket bodies are much likelier to break up into debris that survives reentry and falls back to Earth.

Even the smallest of objects can create problems for an aircraft. An object falling from space roughly the weight of a paperclip (about 0.04 ounce or a gram) could cause damage to an airplane if it strikes its windshield or is sucked into an engine. A piece of debris over 0.3 ounce (9 g) could punch a hole in the body of a plane, and an item less than a pound could cause a catastrophic crash.

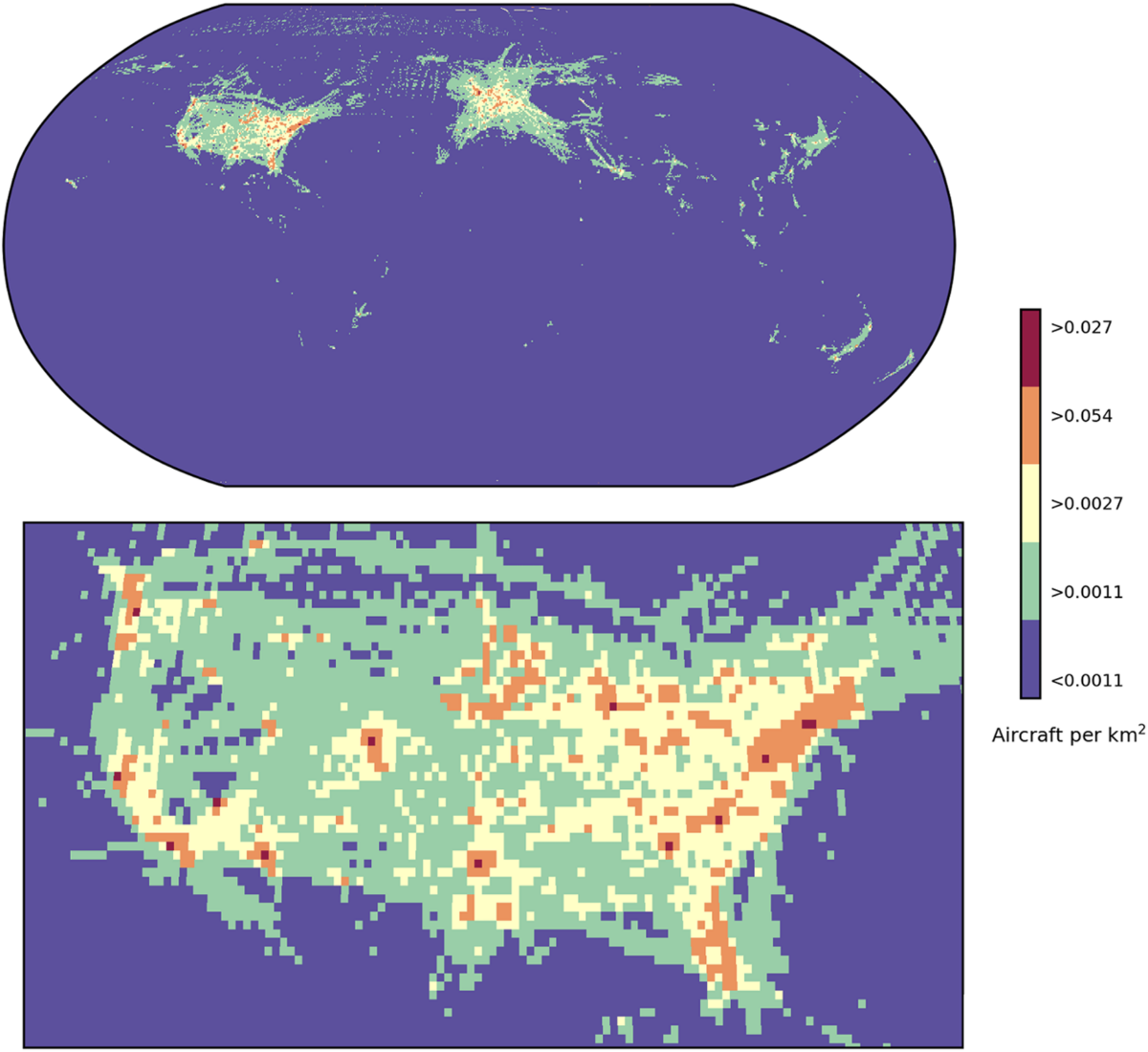

To calculate the odds of such a disaster, the authors analyzed where rockets are most likely to reenter based on historical data of their orbits over the past decade. Then they weighed that information against how crowded Earth’s skies are based on 2023 tracking data from aircraft transponders.

The odds of a collision are still low. Considering the effective exposed area of an airplane (which is larger than the plane itself because of its speed), the study estimates that the likelihood of debris colliding with a plane is roughly 1 in 430,000 each year. However, the authors say that is a conservative estimate, as it doesn’t take into account that rocket bodies break up into many other pieces as they reenter.

Knock-on impacts

As the Long March 5B reentry shows, even predictions of debris can lead to airspace closures and delays, dealing economic costs to airlines and passengers. Under international law, the nation that launched the rocket could be liable for those costs.

To understand how air traffic operations could be disrupted, the team studied the odds of a rocket falling into crowded airspace. They found that the likelihood of an uncontrolled reentry near one of the most crowded major international hubs like Atlanta, New York, or London is about 0.08 percent annually. But when considering busy areas around other major airports and in crowded airways worldwide — such as parts of the northeastern U.S., northern Europe, and around major cities in Asia — the annual probability of rocket debris falling into a heavily trafficked region is 26 percent.

It does not help that uncontrolled debris is difficult to predict in advance. The U.S. Federal Aviation Commission noted in a 2023 report that even within 60 minutes of reentry, the potential area where debris could fall still spans 1,240 miles (2,000 km).

National and international organizations have sounded the alarm on uncontrolled rocket reentries and proposed policies to reduce safety risks. But, the authors note, there is very little enforcement to prevent such incidences from occurring.