A report published Tuesday raises serious questions about NASA’s ability to effectively function as the nation’s preeminent space agency.

The 218-page document, assembled by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) at the behest of Congress, warns that NASA is prioritizing short-term missions and commercial contracts over the people and technology that make its out-of-this-world activities possible.

Per the report, the space agency’s emphasis on near-term victories and overreliance on private contractors — whether by choice or under external pressures, including budgetary — comes at the price of degraded infrastructure and exodus of talented personnel.

“NASA should rebalance its priorities and increase investments in its facilities, expert workforce, and development of cutting-edge technology, even if it means forestalling initiation of new missions,” the NASEM said.

NASEM operates under a congressional charter and comprises private and nonprofit institutions that provide independent analysis on public policy decisions. The academies release decadal reports for both astronomy and planetary science, effectively giving NASA and Congress a roadmap for funding over the next ten years. The studies take years to put together and are highly influential within the astronomy and space communities.

Tuesday’s publication, titled NASA at a Crossroads, is a bit of an outlier. The report was requested by Congress in 2022 amid growing pressure from China, which in June became the first nation to return samples from the Moon.

NASEM members met with experts, visited NASA centers, sent requests for information, and reviewed agency documents to inform their conclusions. The outlook, the organization says, may be bleak.

The state of NASA

The NASEM report paints the picture of an agency in turmoil from top to bottom.

“During its inspection tours, the committee saw some of the worst facilities many of its members have ever seen.”

— NASEM report

Internal and external pressure from NASA and its benefactors has placed it in a bit of a tight spot. Agency senior center managers told researchers they would prefer to spend additional funding on new missions rather than facility maintenance or personnel training. But per the U.S. Committee on Human Spaceflight, NASA annually spends about $3 billion on missions it cannot afford.

“Each dollar of mission support that previously had to sustain a dollar of mission activity now has to support $1.50 of mission activity, effectively a 50 percent increase,” the report says.

In short, the agency’s workload is expanding more rapidly than its mission budget — and that’s absorbing money that could be better spent elsewhere.

NASA infrastructure is essential to the agency’s mission and is used by other agencies and private partners. But “chronic insufficient funding” has resulted in about 83 percent of the agency’s facilities, many of which were built in the 1960s, exceeding their design life. These aging assets are difficult to maintain, soak up valuable personnel time, and make NASA less attractive to prospective talent.

“During its inspection tours, the committee saw some of the worst facilities many of its members have ever seen,” NASEM said.

For example, according to the report, NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) — a network of radio dishes around the globe that receive and transmit data from missions — is too degraded to support current and planned projects without disrupting others. DSN locations over the next decade will cost tens of millions to maintain, it predicts, while contending with a thin workforce and failing infrastructure. The DSN budget in 2022 was $200 million, down from $250 million in 2010.

NASA’s employee turnover rate is largely consistent with the commercial space industry, per the report. But agency employees cited lower salaries and greater private sector involvement as deterrents to working there. In addition, NASEM found that women and minorities are underrepresented, leaving plenty of talent untapped.

Researchers worry the prevalence of certain commercial contracts, such as fixed-price or milestone-based, could make matters even worse by turning NASA engineers into contract monitors. These agreements stifle agency personnel by reducing hands-on work while opening the door for private companies to develop technology that, in the NASEM’s view, should be built in-house.

“Innovative, creative engineers don’t want to have a job that consists of overseeing other people’s work,” said ex-Lockheed Martin executive Norm Augustine, the lead author of the report, during a virtual briefing Tuesday afternoon.

A tight budget

NASA’s tendency to prioritize short-term missions over long-term success stems in part from a constrained budget environment.

Between 2014 and 2023, the agency’s funding actually increased by an average of more than 3 percent over the previous year. But over the past two decades, its purchasing power has essentially held flat while mission complexity has grown. During the peak of the Apollo program, NASEM estimates, purchasing power was about three times higher.

The 2023 debt ceiling agreement capped increases to federal non-defense discretionary funding for fiscal years 2024 and 2025, and NASA has felt the impact. Its 2024 budget left it with about half a billion less than it had in 2023. The 8.5 percent discrepancy between what the agency requested and what it received was the largest since 1992.

The funding cut gives NASA little wiggle room for certain missions such as Mars Sample Return, for which the agency has requested help from private industry to lower costs. Another high-profile program, the Chandra X-ray observatory, was placed on the chopping block, and several others have been delayed.

It could be a similar story in 2025. The White House’s 2025 NASA budget request, which seeks the same amount awarded in 2023, has been marked up by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, with the latter’s proposal reading much more favorable.

Under the House budget, NASA would receive $200 million less than requested, a slight increase over 2024 in real dollars but below the current rate of inflation.

The biggest loser would be the Science Mission Directorate, which would get $7.3 billion — the same as 2024’s allocation, which represented the first cut to NASA’s science budget in a decade. A coalition of scientific organizations and more than 40 members of Congress believe the agency needs closer to $9 billion to support its dozens of space science missions.

Mars Sample Return could also suffer despite the House requiring it to spend $450 million more than NASA requested.

That’s because it would provide less than half of that money, leaving NASA to scrounge up the rest by axing other planetary science projects. The House would require full funding for certain programs, so only a few — namely Discovery, New Frontiers, and fundamental research — would be candidates for cuts. Within those programs are the critical VERITAS mission to Venus and Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s moon Titan, both of which could be jeopardized.

Also at risk is the Artemis lunar program, the successor to Apollo. NASA asked to shift funding from flight-proven components to novel technology that will be used on future missions, including the return of Americans to the Moon during Artemis 3. But the House mandates that the former programs maintain their historical levels of funding.

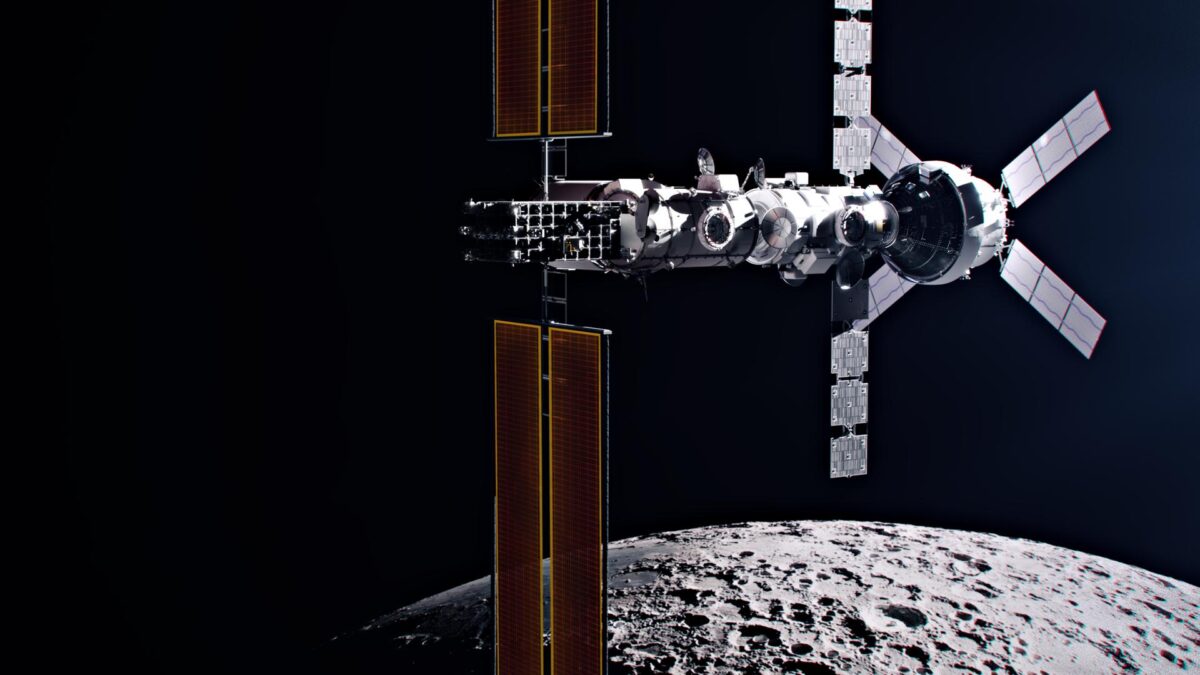

According to an analysis by Casey Dreier, head of policy at The Planetary Society, that creates a roughly “half-billion-dollar hole” for the Lunar Gateway space station. To fill it, NASA will need to either redirect funds from other programs or significantly cut Gateway funding.

The Artemis 2 and Artemis 3 missions have already been pushed to September 2025 and 2026, respectively, and NASA has hinted at delays to future missions. Earlier this year, it suddenly canceled development of the VIPER lunar rover due to budget uncertainty.

“Future funding is clouded by the ever-declining federal discretionary budget from which NASA support is provided,” the report says.

Things may improve in 2026 when spending caps are lifted. However, NASA within the last year and change has lowered its budget projection for 2030 from about $30 billion to $28 billion.

Instant gratification

NASA’s inefficiencies arise not just from its meager budget but also from how the agency uses it, the NASEM says.

The agency is often stretched thin by the sheer number of projects it pursues, causing setbacks to individual missions as in the case of Mars Sample Return or the James Webb Space Telescope.

Further, according to the report, many NASA leaders dismiss the need for long-term internal strategy, citing immense influence from Congress on its annual projects and budget. In short, the perception within NASA is that doing so would waste resources.

“Even planning for the advancing Artemis program lacks certain action-specific details associated with an architecture that is more complex and interdependent than Apollo,” the NASEM said.

But the lack of foresight by leadership results in unrealistic initial cost estimates, creating a domino effect that forces underfunded missions to pull money from other programs. The NASEM characterizes NASA’s internal research and development program, for example, as underfunded.

“The inevitable consequence of such a strategy is to erode those essential capabilities that led to the organization’s greatness in the first place and that underpin its future potential,” the report reads. “The profound negative consequences of this are felt far beyond the specific projects producing the delays and unanticipated funding demands.”

The NASEM recommended a total overhaul of NASA’s long-term mission planning process, including required “need dates” for capability and component needs. It also suggested that as responsibility shifts from NASA centers to specialized mission directorates, the agency should make sure its checks and balances are providing enough oversight.

An eroding base

Because NASA puts so much energy into its missions, the agency has neglected the engine that drives them: personnel and infrastructure.

Since 2017, only two NASA congressional authorization acts — which allocate funds from the Treasury Department and establish new programs and policy focuses — have been made law. According to the report, “this inhibits the forecasting of workforce, infrastructure, and technology needs.”

“In this case, NASA is more of a contract monitor than a technical organization capable of taking humanity into the solar system.”

— NASEM report

On the infrastructure side, the NASEM recommended NASA work with Congress to create a revolving working capital fund (WCF) financed by the government and users of NASA facilities, similar to those for other federal departments. The agency could use the money to eliminate its maintenance backlog over the next decade and make continuous infrastructure enhancements.

Equally concerning is the agency’s workforce, which faces more competition for employment than ever before. Creating a commercial space ecosystem was a U.S. national policy goal for decades, and NASA has benefitted from working with private companies. These partnerships are necessary, the report argues, but verging on excessive.

Researchers contend that specialized, early phase mission work should be handled in-house, or NASA risks losing the talent that has propelled it thus far. Fixed-price or milestone-based contacts, such as the Artemis Human Landing System (HLS) agreements with SpaceX and Blue Origin, take agency personnel out of the picture. Many employees told researchers they would like more training or opportunities to hone their skills.

“In this case, NASA is more of a contract monitor than a technical organization capable of taking humanity into the solar system,” the NASEM said. “The concern is not only an erosion of ‘smart-buyer’ capability, but also of the capacity to invent and innovate.”

There is also the risk that a commercial provider exits the market or fails to deliver. A NASA inspector general report, for instance, blames contractor Boeing for certain delays associated with the Artemis program.

The NASEM directs NASA to invest in “early-stage, mission-critical technologies” that commercial firms have yet to crack, emphasize more hands-on work, and unearth new talent by targeting underrepresented demographics.

It could also seek to update the NASA Flexibility Act of 2004, which was implemented partially in response to the space shuttle Columbia accident and dictates what the agency can pay employees. By securing greater appointment and hiring authority, it could ease the burden of attracting and retaining talent.

Houston, do we have a problem?

NASA’s budget woes have been well documented. The NASEM report, however, raises new concerns about how the agency uses what little it receives.

It’s not all NASA’s fault — the agency’s effort to scale back Mars Sample Return, for example, faces opposition from the House. If NASA must divert funding from other projects to support that mission, the blame would land squarely on Congress.

But the report doesn’t spare the agency scrutiny of its own shortcomings. Although lawmakers control the budget, the neglect of long-term mission planning and inability to produce accurate cost and schedule estimates borders on ineptitude. Infrastructure and technology are dated. And private firms are snapping up talent faster than NASA can produce it.

Given the pressure the agency faces internally, from the government, and from its contractors, these issues are unlikely to resolve themselves without some serious effort. The hope is that the adoption of the Senate’s more favorable budget proposal, and the lifting of spending caps in 2026, could give it some much needed support. But NASA’s fortunes will also hinge on a reassessment of its priorities.