Therefore, forget about the Death Star, this amalgamation of blinking hardware floating in Earth’s orbit would be target numero uno. But would it be wise to pull the trigger?

It’s A Trap

Here’s the short answer: Orbital fireworks are not likely to begin anytime soon.

“Everybody assumes that if we get somebody that shoots at me in space, we’re going to shoot back in space. Well, that’s a horrible idea,” says Colonel Shawn Fairhurst, the deputy director of Strategic Plans, Programs, Requirements and Analysis at the Air Force Space Command.

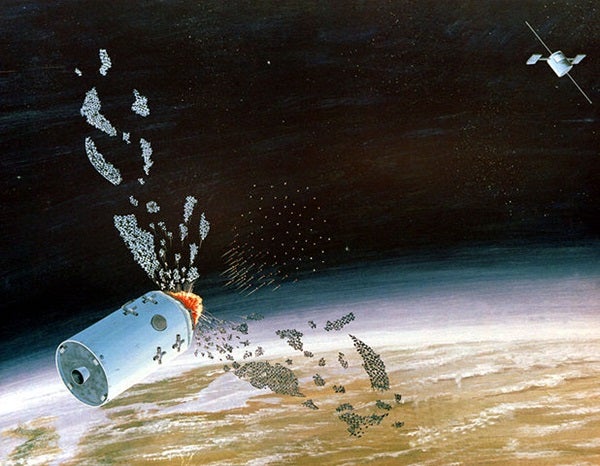

“When you blow something up on the ground, it falls back to the ground. If you blow something up in the air, the airplane comes back to the ground,” he says. “The problem is, when you blow something up in space, it creates debris that never comes down.”

We have little ability to control or defend against that debris, which means the potential for collateral damage is high. It doesn’t take much to shred metal when something is moving at 17,000 miles per hour, as objects in low Earth orbit are. A paint chip estimated to be the size of a grain of sand left a quarter-inch pit in a space shuttle window, and the panes must occasionally be replaced because of similar impacts. Something the size of a marble could be devastating to a satellite.

When the Chinese destroyed one of their own satellites with a missile in 2007, it created a cloud of debris, each piece with the potential to destroy satellites and cripple communication and financial networks. Even if an attack were targeted at one nation’s satellites, the fallout would be a roll of the dice—best to avoid the matter of blowing things up in space altogether.

The Air Force simply considers the risks involved with destroying something in orbit to be too high, according to Fairhurst. He says they’re focusing on making their satellites more maneuverable and redundant, which makes them less lucrative targets. The other priority is to prevent an enemy from ever launching a missile toward a satellite in the first place.“Instead of building giant satellites that are sitting ducks … can we look at breaking those things into smaller pieces so if you lose part of it the rest of the capabilities still go on?” he says. “If they see a threat, can they move out of the way?”

Other potential, less chaotic, satellite attacks include hacking, jamming a signal or blinding its sensors with lasers. Simply nudging a satellite out of orbit could be enough to disrupt it temporarily as well. All offer means of undermining the military’s abilities, and the Air Force worries that such tactics could play a role in future conflicts, Fairhurst says. While he stresses that a physical attack is not their goal, he says the Air Force is prepared to defend its assets.

We Come In Peace

“There’s this idea connected with space that it should be used for peaceful purposes,” says P.J. Blount, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Luxembourg and the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Space Law. “And that idea extends a heightened status to space for states not to engage in these types of activities.”

That peaceful designation for outer space is based on the 1967 “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies,” better known as the pithier “Outer Space Treaty.” It’s administered by the United Nations, and it states, among other things, that space is for peaceful uses only, and forbids placing weapons of mass destruction in orbit. It also forbids weapons of any sort on the moon. So far, the treaty has been upheld, in large part.

It doesn’t prevent the use of space for military activities, so things like spy satellites and the like are allowed, and it’s been generally accepted that defensive operations are allowed as well, Blount says. The treaty doesn’t lay down hard and fast rules either — it’s not clear what would happen should anyone violate it.

But, for all the posturing and the potential advantages of destroying one another’s satellite networks, it never happened.

“The United States and the USSR were adversaries and they worked together to ensure that conflict did not erupt in space,” Blount says.

Uncertain Future

Today, the landscape has changed. Orbits around the Earth are getting more crowded. Smaller countries like Iran and North Korea have become players in the space race, and there are worries that they may not hesitate to bring war to outer space. North Korea, especially, does not rely on satellite networks the same way that we do, so they have far less to lose by taking them out.

And the balance of pros and cons could change even more as we begin to further expand the range of our activities in space. Colonies in orbit or on another planet, as well as mining operations in space, bring with them two of the most potent ingredients for war — territory and resources.

Creating laws that define right from wrong in space would help to alleviate future problems, but the three space superpowers — the U.S., Russia and China — seem hesitant to put any in the books. Though Russia and China have been pushing a treaty banning weapons in orbit or on celestial bodies, Blount says it’s more public relations act than honest effort. They know the treaty has little chance of being approved, he says, giving them the chance to continue developing space capabilities while appearing to work towards peace.

The U.S. has taken much the same approach. President Bush refused to negotiate any treaties, according to Blount, and efforts under president Obama didn’t get anywhere. Meanwhile, Congress recently advocated for a “Space Corps” within the Air Force — though the military branch did not support it — dedicated to defending U.S, interests in space. The Air Force sees its space spending increase by eight percent under the Trump administration’s latest budget proposal. The money is largely earmarked for research and development and includes more funds for a missile warning system and space forces.

“I think all three of these states see the ambiguity in the rules as more beneficial to them than definitions at this moment,” Blount says. “You see a lot of talk about wanting to de-weaponize space, but don’t see a lot of movement in defining the rules.”

The end result is a continued push by all three nations toward military preparedness in space. It’s true that a space war might be something no one wants. But then again, what is everyone preparing for?