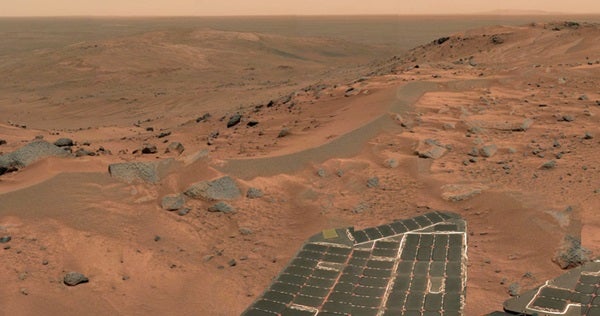

Mars rover Spirit has ended its year-long ascent up Husband Hill, and, like any tourist, is pausing to take in the view. Mission scientists are acquiring images for a full 360° panorama that , for the first time, will include terrain on the far side of the Columbia Hills.

Chris Leger, a rover planner at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, says seeing the first summit images “was every bit as exhilarating as getting to the top of any mountain I’ve climbed on Earth.”

The summit is 269 feet (82 meters) above the surrounding plain of Gusev Crater, and Spirit now sits at an elevation 348 feet (106m) higher than its landing site. “That’s no Mt. Everest, but it’s a heck of a climb for our little rover,” says Steve Squyres, principal investigator for the rovers’ science instruments. “When we first touched down at Gusev Crater on January 4, 2004, the Columbia Hills looked impossibly far away.”

Spirit and its twin rover, Opportunity, were designed to operate for a minimum of 3 months. They passed that point in April 2004 and are now 16 months “beyond warranty.” In that time, the rovers have inspected dozens of rocks and soil targets in a pursuit for geological evidence of water in the martian past.

“The mission has far exceeded our wildest dreams,” Mars Exploration Rover program scientist Curt Niebur tells Astronomy.

Opportunity, which is exploring a region called Meridiani Planum on the opposite side of Mars, quickly found evidence a salty sea once existed at its landing site. But Spirit saw only chemical traces of water until it drove 2 miles (3 kilometers) cross-country and trekked into the Columbia Hills.

Spirit landed in Gusev Crater, a geographic bowl about 95 miles (150 km) across. Scientists targeted Gusev because its terrain suggests the crater once held a lake, but on the plains, volcanic deposits have covered any geological evidence of an ancient lakebed. A meteorite impact may have elevated the Columbia Hills, exposing the older rock layers that bear witness to water’s physical and chemical action.

“This climb was motivated by science,” Squyres says. “Every time Spirit has gained altitude, we’ve found different rock types.”

Five months after setting down on Mars, Spirit reached the hills’ base. It immediately began finding rocks with wetter histories. “It wasn’t until we got to Husband Hill that we were able to see rock outcrops that really opened our eyes to what Mars was like billions of years ago,” Niebur explains.

“What we want to do is figure out which layers were on top of which other layers,” says Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator for the rovers. “Understanding the sequence of layers is equivalent to having a deep drill core from … beneath the plains.”

“Earthlike climates persisted for a very long time,” says Niebur. What’s more, “We’re seeing a recurring earthlike climate on Mars deep in the past” — more than 2.5 billion years ago.

Spirit’s high-altitude vantage point on Husband Hill offers views of possible routes south into what appear to be layered outcrops. The peak is the tallest of the Columbia Hills, which lie east of Spirit’s landing site. NASA has proposed naming the range in tribute to the space shuttle Columbia’s last crew. The tallest of the hills commemorates Rick Husband, Columbia’s commander.

Dust accumulation on the rovers’ power-generating solar panels was expected to limit their lifetime on Mars, but the Red Planet has been kind. Summertime winds have repeatedly whisked the panels clean. Spirit has driven a total of 3 miles (4.8 km), while Opportunity’s odometer reads 3.56 miles (5.7 km).

How much longer will they last? “That’s the question we ask ourselves every day,” Niebur says. “Every day is a gift the excellent engineers at JPL have provided us.”