Editor’s note: This article was first published March 29, 2024, and has been updated.

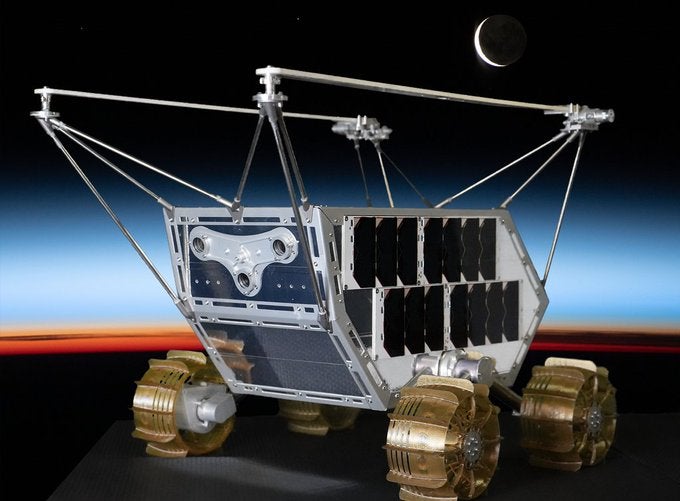

After becoming the first commercial operator to land a spacecraft on the Moon last year, Intuitive Machines is preparing its follow-up mission, IM-2, for launch later this week. Aboard the craft will be several NASA payloads, including a drill and mass spectrometer that will study the lunar South Pole region. There will also be a rover called the Mobile Autonomous Prospecting Platform (MAPP), built by Colorado company Lunar Outpost.

But three other projects from the MIT Media Lab will catch a ride to the Moon, too.

The MIT Media Lab is famous for its interdisciplinary approach to technology, melding technology and human culture — and the projects that its Space Exploration Initiative has built for IM-2 reflect that. Upon landing, a sci-fi inspired helper robot will crawl around the rover, checking its temperature. A camera mounted to the MAPP rover will take the first digital 3-D images of the Moon’s surface. And the Media Lab has also prepared a successor to Voyager 1’s Golden Record, which carried recordings of sounds from Earth; this smaller silicon version will bring a symbolic record of people’s thoughts about space exploration to the Moon.

“We work with students who are scientists, researchers, engineers, artists, musicians — kind of across the board, thinking more about bringing all of humanity and culture and everything into space so that it’s somewhere we want to live, and think about how we can bring those technologies back to Earth and benefit from them,” says Cody Paige, director of the Space Exploration Initiative.

The tiny but mighty AstroAnt

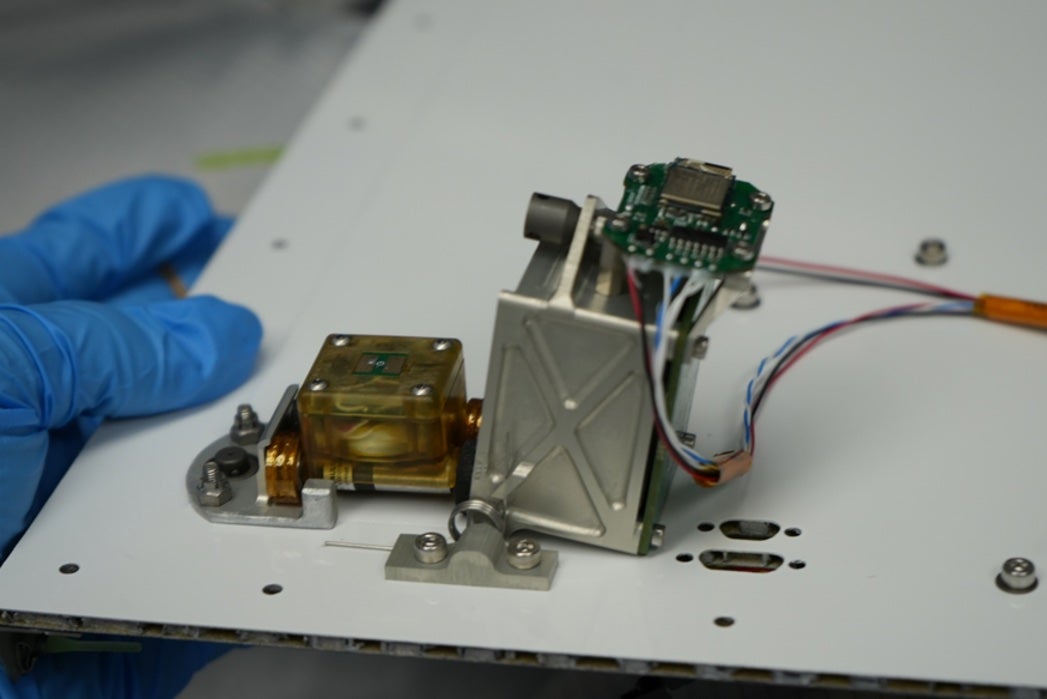

At just over an inch (3 cm) across, the AstroAnt is a robot small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. But it has a big mission — to monitor the health of the MAPP rover by taking its temperature.

The Moon is known for its extreme temperature swings from unbearable heat to freezing cold. Sunlit areas can reach 250 degrees Fahrenheit (121 degrees Celsius) near the lunar equator. But in places like crater floors near the Moon’s poles that are permanently in shadow, temperatures can drop to a frigid –410 F (–246 C).

“You want to make sure that all of your active heating or active cooling [systems on the rover] are working the way they’re supposed to and that you’re not getting hotspots, say, on the surface of the rover where you wouldn’t be expecting to have them,” says Paige.

AstroAnt won’t touch the lunar surface — instead, like R2-D2 in Star Wars, it will ride along on the larger vehicle and roam across it. The AstroAnt’s four wheels are magnetic, allowing it to stick to the top of the rover, where the MAPP’s radiator is located. The AstroAnt also has a small metal box, dubbed the “garage,” that acts as a charging station. The robot can run for a few hours before it needs to be recharged.

Monitoring a rover’s status with a miniature buddy has advantages, says Fangzheng Liu, AstroAnt’s project lead and research assistant at MIT’s Media Lab. “Because the robot is so tiny, they can get into very limited spaces that cannot be reached by, say, a human astronaut or some bulky robotic arms.”

The AstroAnt’s first venture into space is a technology demo, but future versions of the AstroAnt could feature with sensors or small hammers that could tell engineers back on Earth if the rover developed any cracks on its surface. Eventually, its builders envision sending sci-fi-esque swarms of AstroAnts to aid researchers in planetary and deep space exploration and be used on satellites and future space stations.

Mapping the Moon in 3-D

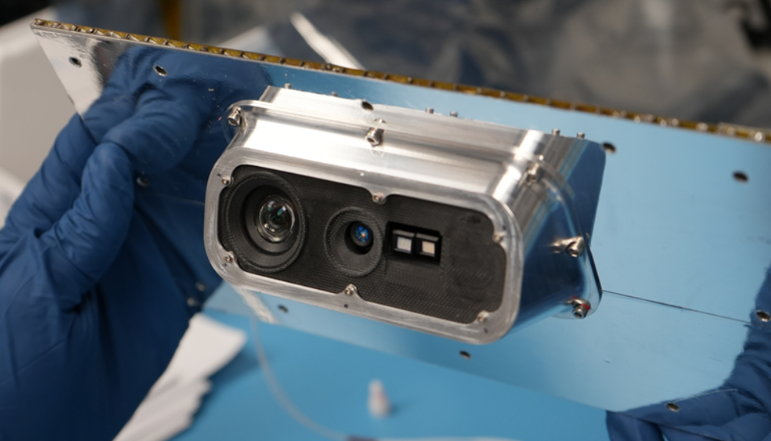

Another payload from the Space Exploration Initiative will feature a camera that will be the first digital 3-D camera on the surface of the Moon. Astronauts have previously taken 3-D stereo images on film — sometimes by simply snapping two photographs from slightly different positions. But this off-the-shelf camera — a version of Microsoft’s Xbox Kinect — can capture high-resolution depth data of its environment.

Scientists and engineers are particularly keen to obtain information of the terrain and geology of the lunar south pole region, where IM-2 is landing. Space programs around the world are targeting this region in large part because of the potential to find water ice in permanently shadowed craters.

The camera — which the team field tested on the remote Norwegian archipelago Svalbard — sits underneath the rover. The data it collects will help future missions and lunar landers to navigate the rugged terrain that they are expected to encounter at the Moon’s south pole.

“You’re slingshotting these landers around the Moon and having to land in that [precise] of a point is very difficult. But these types of cameras will help us get there,” says Paige.

These 3-D images could also one day be used to train future astronauts, like those in NASA’s Artemis program who will be traveling to the lunar south pole, adds Paige. “The data that we’ll be using from there will essentially be able to build out a virtual environment of the pathways and what that lunar rover is seeing,” says Paige.

Uniting humans on the Moon

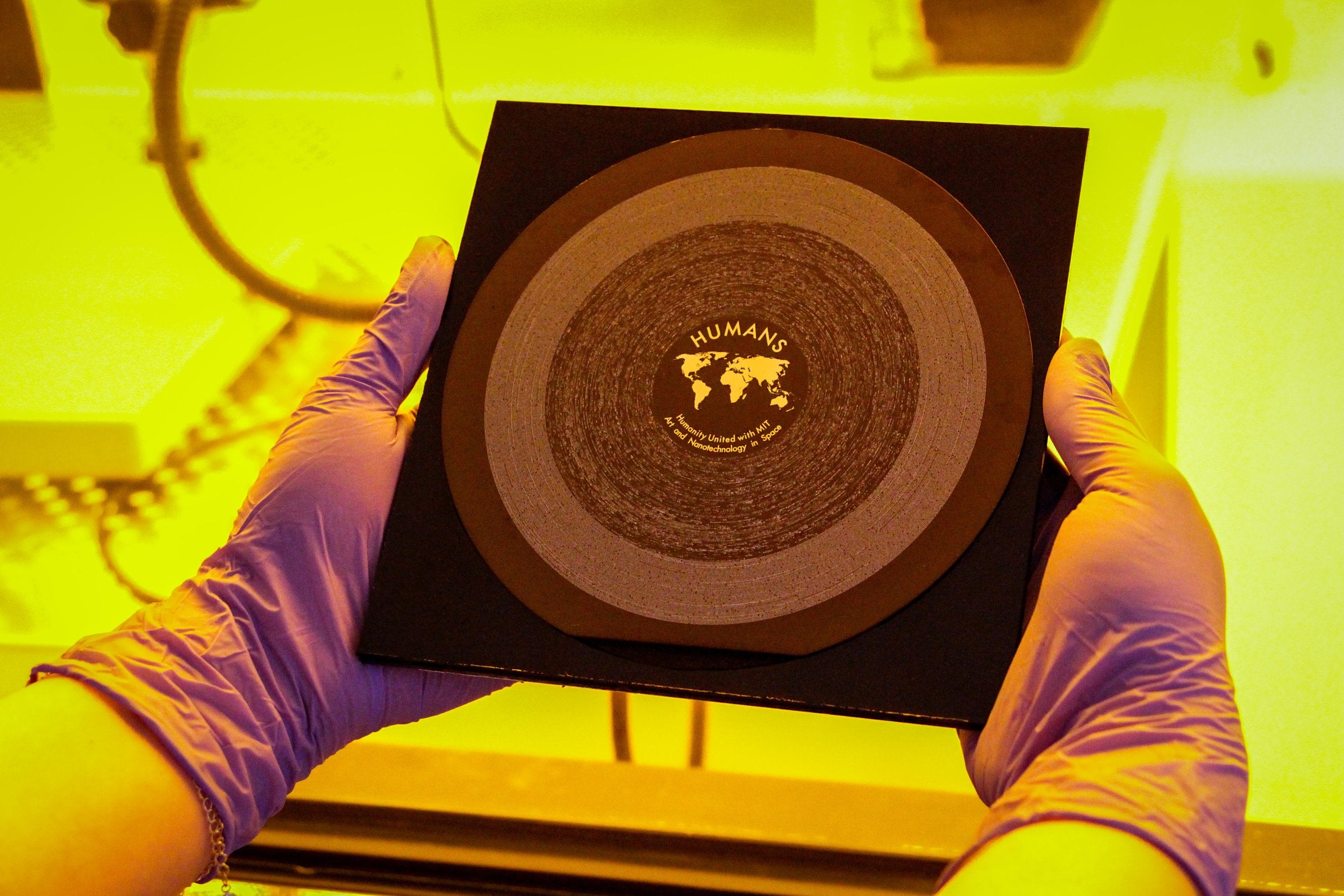

The Space Exploration Initiative’s final payload is inspired by Voyager 1’s Golden Record. Dubbed Humanity United with MIT Art and Nanotechnology in Space (HUMANS), it’s a 2-inch silicon record etched with the words or waveforms of 1,234 human voices in different languages, explaining what space means to them and to humanity. A larger 6-inch version of the disk exists on the International Space Station.

Of the three payloads, HUMANS has the least to do when it reaches the Moon, but it may leave the longest legacy. Long after the AstroAnt powers down and MAPP’s depth camera shuts off, the HUMANS record will lie in waiting, ready to relay the thoughts of the first generation of humans to establish an enduring presence on the Moon.