Baikonur awoke to a cool dawn on Nov. 20, 1998, the ubiquitous murk of a dour winter’s sky and the sober tan landscape of the featureless Kazakh steppe hardly conducive to a fine day.

Yet on that frigid Friday, a quarter-century ago, all eyes in this desolate corner of Central Asia lay upon a 17-story Proton-K rocket, lonely and gaunt atop Baikonur’s Site 81 launch pad. Minds from a dozen nations willed it to fly well. And hearts ached for success as a new age began: the age of the International Space Station (ISS).

At 11:40 a.m. local time, the ethereal calm was abruptly broken by a harsh staccato crackle and gout of blood-orange flame as the mighty Proton came alive, pummelling the Earth with 2.3 million pounds (1 million kilograms) of ground-shaking fury. It rose ponderously through a smudge of grey smoke of its own making, shattering the lens of a launch pad camera as it went. Nine minutes later, the beast pushed its school-bus-sized cargo into space.

That cargo was Zarya (Russian for ‘dawn’), also known as the Funktsionalno-gruzovoy blok (‘FGB’ in Cyrillic, translatable to ‘functional cargo block’), the first structural piece of the ISS. It furnished the nascent station with electricity, storage, propulsion and guidance. Forty-one feet (12.5 metres) long and spanning 13.5 feet (4 metres) at its broadest point, Zarya tipped the scales at 42,600 pounds (19,300 kilograms). Its twin solar arrays sprouted like glistening wings to a length of 35 feet (11 metres).

The ISS was first proposed in 1984

But Russia was not originally part of the ISS. When President Ronald Reagan announced plans for a space station in January 1984, built by the United States and its allies in Europe, Japan and Canada, he wanted the facility (named ‘Freedom’) built within a decade. But costs rocketed and with each redesign the dollar-guzzling Freedom grew smaller, less capable and fell further behind schedule. In June 1993, it came close to cancellation.

Later that year, Russia came aboard as a new partner, her decades of building space stations furnishing a much-needed shot in the arm. It put her scientific know-how to good use in the unsteady times after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and ensured her technological capabilities were not sold to rogue states like Iran or North Korea.

And this partnership has endured to this day, though not without incident. Relations have soured in the last decade, following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Bellicose rhetoric from both sides has threatened outright withdrawal from the ISS, a dire eventuality which so far has not come to pass.

Although built by Russia as part of its ISS contribution, Zarya is owned by the United States and nestles at the junction between the station’s Russian and U.S. halves. At its aft end is the Russian Operational Segment, a cluster of five pressurised modules boasting living quarters, an airlock, a cargo staging area, a science lab and a docking hub. And at Zarya’s forward end is the U.S. Operational Segment, with U.S., European and Japanese labs, a Canadian robotic arm, three connecting nodes with sleep stations, hygiene and gym facilities and a dome-like cupola, affording 360-degree panoramic views of the Earth.

Anchored by a 310-foot-long (94-metre) truss, a colossal metallic backbone housing solar arrays, batteries and radiators, the ISS pressurised interior of 16 modules boasts a habitable volume of 13,696 cubic feet (388 cubic metres), equal to a six-bedroom home.

As the initial cornerstone of this Earth-circling Great Pyramid of our age, Zarya today is a narrow, cluttered place: internally, it presents itself as a locker-studded passageway, devoted to storage. Its 9,130-and-counting days spent so far in space have seen it orbit the home planet over 146,000 times, once every 93 minutes.

Related: How to see the ISS from your backyard

269 people have called ISS home

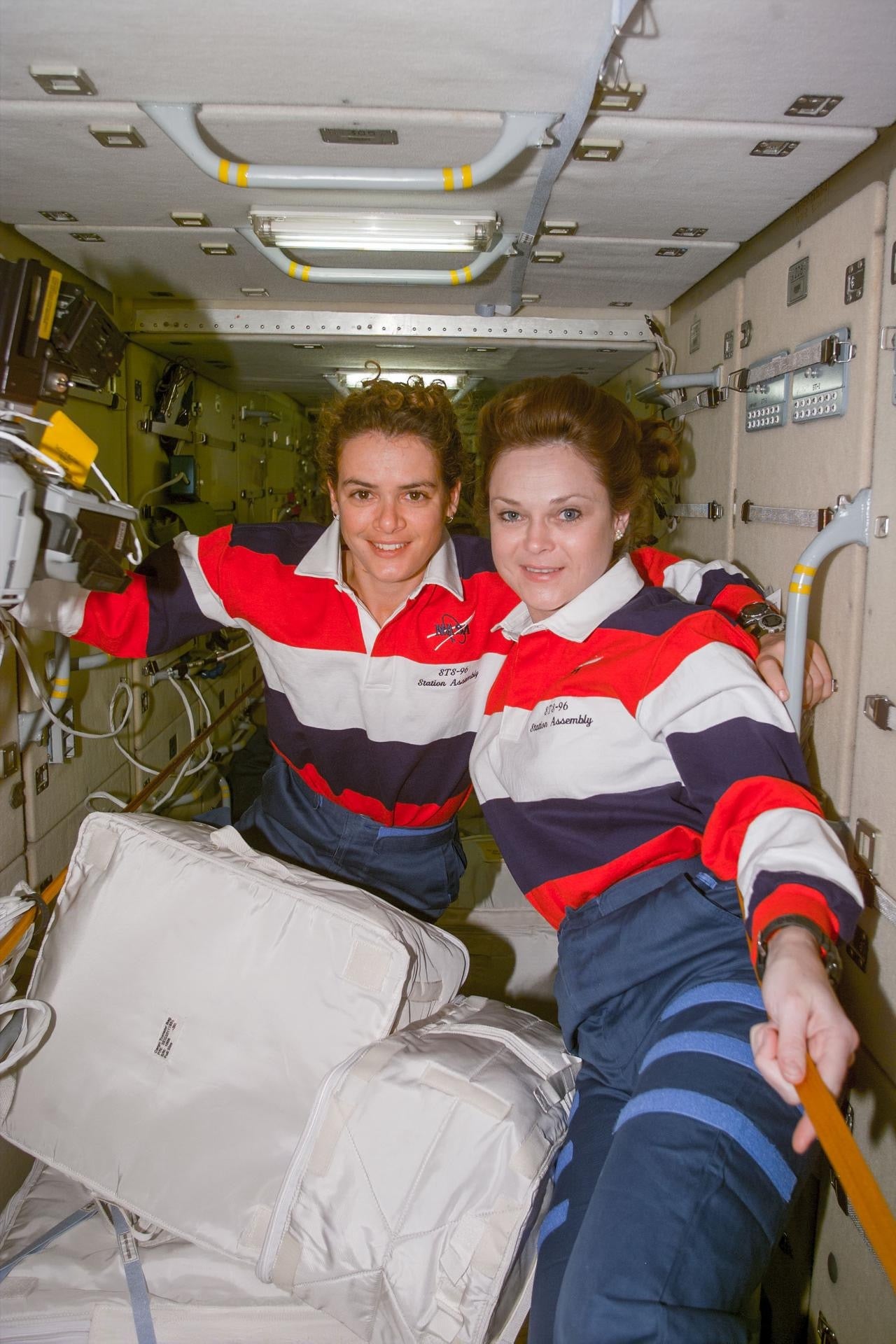

Across that quarter-century bundle of years, 269 people from 21 nations called this place home for periods as short as a week to as long as 371 days, including the first national space travellers from South Africa, Brazil, Sweden, Malaysia, South Korea, Denmark and the United Arab Emirates. Their ages ran from twentysomethings Mark Shuttleworth and So-yeon Yi to septuagenarian Larry Connor, their professions from fighter pilots to physicists, doctors to film producers, entrepreneurs to actors. But all shared a common raison d’être: to explore and live on an unknown frontier.

The station’s human presence has lasted semi-continuously since Space Shuttle Endeavour visited in December 1998 to attach the U.S.-built Unity node to Zarya. Occupation has been continuous since November 2000, when Expedition 1’s Bill Shepherd, Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev arrived aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft for a five-month stay.

For over two decades, 59 visiting crews and 70 overlapping long-duration expeditions have arrived and departed on 67 Soyuz ships, 37 Shuttle missions and ten SpaceX Dragon flights. Food, clothes, hygiene items, experiments, hardware, tools and supplies have been trucked to the station by a regular cadence of 150 (and counting) supply ships from Russia, Europe, Japan and NASA’s commercial partners, Northrop Grumman and SpaceX.

Crews have set many empirical records, including the greatest time spent in space across multiple missions by a man (Gennadi Padalka, 878 days) and a woman (Peggy Whitson, 675 days). Others include the longest spacewalk (eight hours and 56 minutes, set in March 2001), the longest single mission by a woman (328 days, set in February 2020) and the first all-female spacewalk (set in October 2019).

Cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko’s marriage was solemnised aboard the ISS and astronauts Mike Fincke and Randy Bresnik learned they had become dads whilst living there. National elections were voted upon, marathons were run on the station’s treadmill and long-distance chess contests were played out between astronauts and Mission Control.

As the station’s permanent staff expanded from two or three people earlier this century to a regular rhythm of six from May 2009 and seven since November 2020, there has been a corresponding increase of time available for world-class science, technology demonstrations and educational outreach.

Over the years, the ISS grew from the size of a school bus to a football field. From its orbital perch at 250 miles (400 kilometres), the station brims with hundreds of continuously humming experiments in biology, physics, Earth observations, materials science and technology. It is laying the groundwork for a long-term presence on the Moon and voyages to Mars, through 3D-printing, growing fresh foods and testing advanced life-support systems and inflatable habitats like the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM).

The future of the station

Current plans call for the ISS to be retired and deorbited after 2030, burning up in the atmosphere, its surviving fragments destined for a watery grave in the Pacific Ocean. However, the aging station’s last handful of years remain bright. Houston-based AxiomSpace is developing a suite of research, habitation and entertainment modules for attachment to the ISS for commercial and private use after 2025.

And the international partners’ work continues unabated, as Europe upgrades the information technology capacity of its Columbus lab and Japan pledges up to half the operational time in its Kibo lab to commercial, educational and public entities. As for the United States, since 2005 its Destiny lab has been a U.S. National Laboratory, facilitating over 600 investigations, 70 percent of which originated from private-sector organizations.

But the station’s mainstay has always been international collaboration, as partnerships forged between one-time belligerents continue (albeit shakily in some cases) to stand the test of time. If the ISS is remembered a century from now, it will surely earn repute and perhaps a measure of nostalgia for its role in bringing together disparate peoples, cultures and ideas for the greater good of exploration.