During the Cold War, the U.S. and USSR raced to be first to send robotic and human explorers to the Moon, traversing lunar terrain and returning samples to Earth. These exploits and their scientific returns were crucial to unlocking the history of the Moon — and by extension, the history of our solar system.

But after these initial forays, exploration of our natural satellite hit the doldrums. Following the USSR’s Luna 24 sample-return mission in 1976, the Moon’s surface remained undisturbed by visitors for decades, save for the occasional impact.

Finally, the 1990s saw a revival in robotic lunar exploration as the U.S. and Europe carried out flybys and Japan deployed its first lunar orbiter. This movement gained steam in the 2000s as China and India launched their first robotic missions to the Moon. And in 2013, China’s Chang’e 3 touched down on the Moon — the first soft lunar landing in 37 years.

Today, a new golden age of lunar exploration is in full swing. Although the return of humans to the Moon on crewed Artemis landings remains years away, robotic explorers are already pushing ahead, exploring new regions and deepening our understanding of this ancient, airless world. The rate of scientific return is only set to increase as companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin show promise in expanding access and driving down costs using reusable rockets.

As a result, the Moon is no longer the domain of the two traditional space superpowers; instead, Luna has become a scientific target studied by many nations and private companies.

Robotic landers lead the way

NASA’s Artemis program has evolved into an effort of staggering complexity. (See “How Artemis will land humans on the Moon” for more.) Technological and funding issues cloud exactly when new human footprints appear on the Moon and NASA’s optimistic lunar exploration timetables frequently become fiction. Realistically, the Artemis 3 mission will land a crew on the Moon no earlier than 2028 — if NASA doesn’t settle for a flyby — and the agency will have spent $93 billion to do so.

Robotic explorers are crucial to the Artemis program’s goals, serving as technology testbeds and scouting possible landing sites for resources. To give those efforts a boost, NASA has fundamentally changed its approach to lunar robotic exploration and now relies on commercial services to deliver science experiments to the Moon.

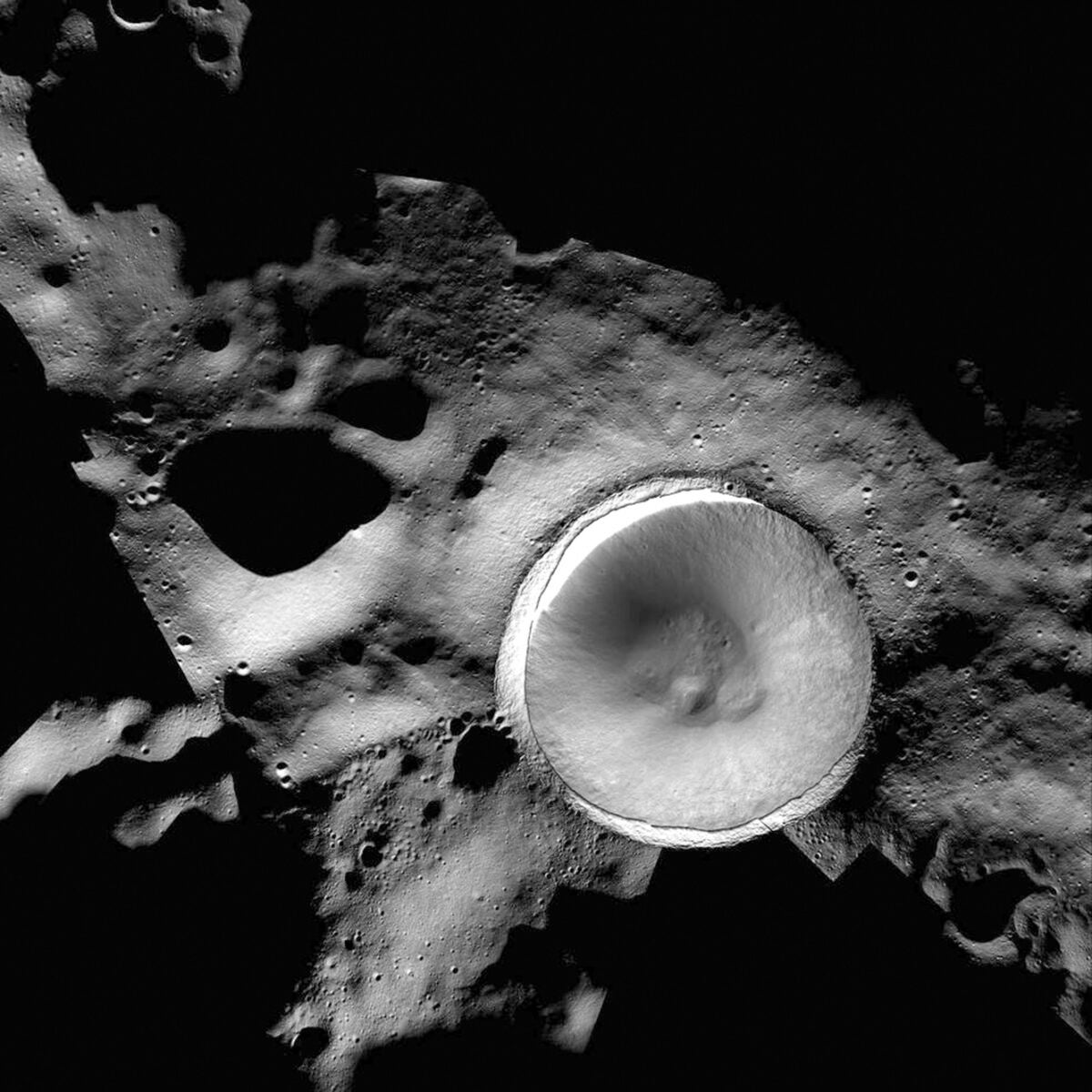

In 2020, NASA initiated the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) project to encourage affordable and rapid delivery of science payloads to the Moon. With the first wave of contracts, startups like Astrobiotics, Firefly Aerospace, and Intuitive Machines took their place alongside established aerospace industry giants. By late 2024, eight CLPS missions had flown or were in advanced development. Of those, three targeted the Moon’s nearside, three targeted the little-explored farside, and three aimed for the region near the lunar south pole. The south pole is a key region of interest: Due to the Sun’s low angle on the horizon, many of its craters have areas that lie permanently in shadow and harbor water ice that could be used by crews living in future Moon habitats.

The initial commercial lunar missions have reminded us that the Moon remains a harsh mistress. Three of the first eight uncrewed landings in NASA’s CLPS program have either failed to complete their missions or been canceled just as the mission was ready to fly.

Astrobiotic’s Peregrine Mission One was the first CLPS payload to fly in January 2024, but a catastrophic fuel leak hours after launch doomed the mission and the spacecraft fell back to Earth after 10 days in space.

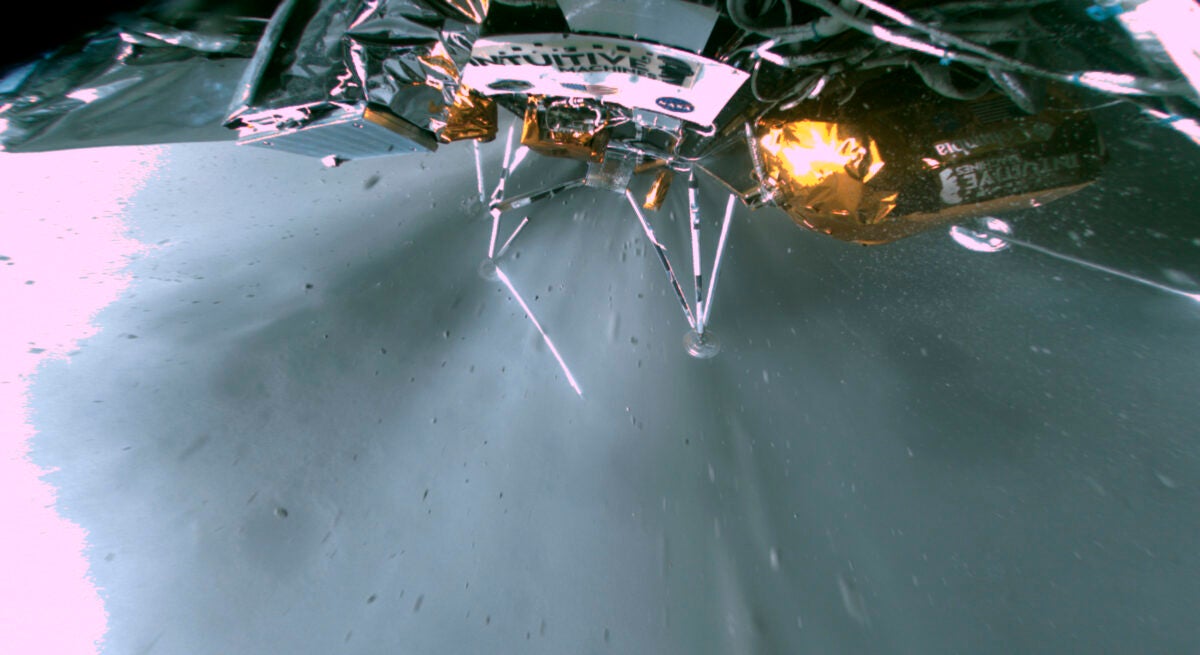

The second CLPS mission in February 2024 was a partial success. The Intuitive Machines IM-1 mission Nova-C lander, nicknamed Odysseus, landed in the crater Malapert A near the lunar south pole, but skidded across the surface as it touched down, snapping a landing leg. The craft came to rest tipped at a 30° angle, but was able to return a limited amount of data before losing power.

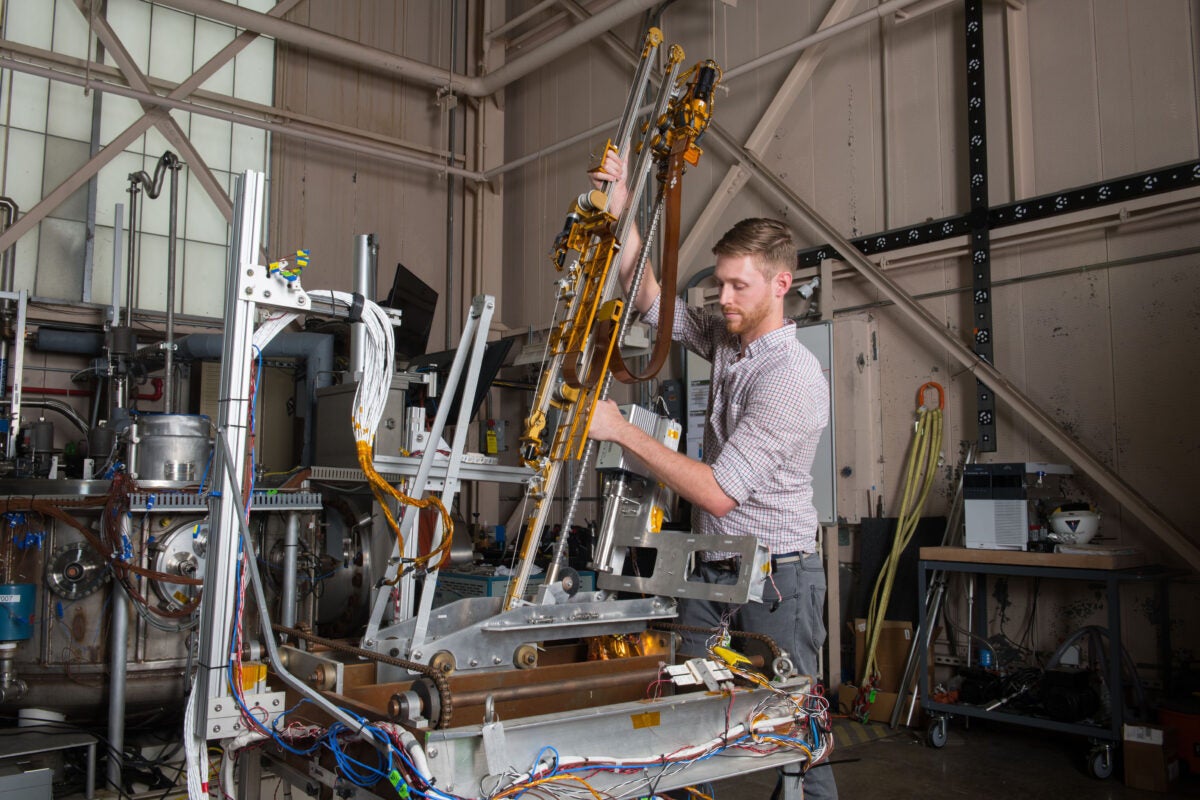

Intuitive Machine’s next mission, IM-2, will land the Polar Resources Ice Mining Experiment (PRIME-1) near Shackleton Crater. The mission is set for an early 2025 launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9, a proven rocket that will launch many CLPS payloads. A drill attached to the lander will bore into the lunar soil and search for evidence of water ice. Sharing a ride aboard IM-2 will be a collection of rovers. These include Japan’s palm-sized Yaoki; the Lunar Outpost Mobile Autonomous Prospecting Platform (MAPP), which will hopefully travel up to 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) with a tiny AstroAnt mini-rover riding piggyback; and the Micro-Nova rover, which is designed to hop around permanently shadowed crater floors.

Also scheduled for early 2025 is the Firefly Aerospace Blue Ghost mission, which will land near Mons Latreille on Mare Crisium, delivering 10 experiments.

Later in 2025, Intuitive Machines’ IM-3 will attempt to land near the enigmatic swirl-shaped feature Reiner Gamma on Oceanus Procellarum. The origin of such lunar swirls remains a mystery, but possible explanations include past or present magnetic anomalies. IM-3 will carry instruments to study the magnetic and electric fields near Reiner Gamma, and will also deploy another MAPP rover.

Unfortunately, in July 2024, NASA cancelled the 2025 flight of the already completed Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER). Instead, the agency plans to land VIPER’s former ride, the Astrobiotic Griffin lander, with no science payload at all.

The CLPS program will progress in 2026 with the Draper SERIES-2 lander targeting the Schrödinger Basin on the Moon’s farside. The Farside Seismic Suite will investigate seismic activity using instruments adapted from the 2018 Mars Insight mission that detected 1,300 marsquakes. The mission will also deploy two small relay satellites to allow the farside lander to communicate with Earth. The second 2026 CLPS payload will be the Firefly Aerospace Blue Ghost 2, which will land a radio astronomy experiment on the radio-quiet farside of the Moon. The mission will also deliver the European Space Agency’s Lunar Pathfinder relay satellite into lunar orbit.

The Moon goes global

In addition to the NASA-subsidized commercialization of the Moon, lunar exploration has become a truly international endeavor. As of late 2024, the international fraternity of lunar efforts includes Russia, the U.S., Japan, the European Space Agency (representing 22 European countries), China, India, Luxembourg, Israel, South Korea, Italy, United Arab Emirates, Mexico, and Pakistan.

In 2025, Canada’s Jeremy Hansen will fly on Artemis 2, becoming the first non-American to go to the Moon. Two astronauts from the European Space Agency (ESA) and two from Japan will be chosen for lunar flights, possibly as early as Artemis 4 or 5. And in an agreement with the UAE, the first Emirati to travel to the Moon will fly aboard an Artemis mission early in the next decade.

China has made amazing strides in robotic lunar exploration. In 2013, it became the third nation to deploy a lunar rover with the Chang’e 3 mission. Chang’e 4 in 2018 became the first spacecraft to make a soft landing on the Moon’s farside. And with Chang’e 5 in 2020 and Chang’e 6 in May 2024, China returned samples from the near and far sides of the Moon, respectively, with the latter feat being another world first.

Historically, when China announces ambitious space plans, they become reality. There is no reason to doubt China’s stated intention to land astronauts on the Moon in the 2030s.

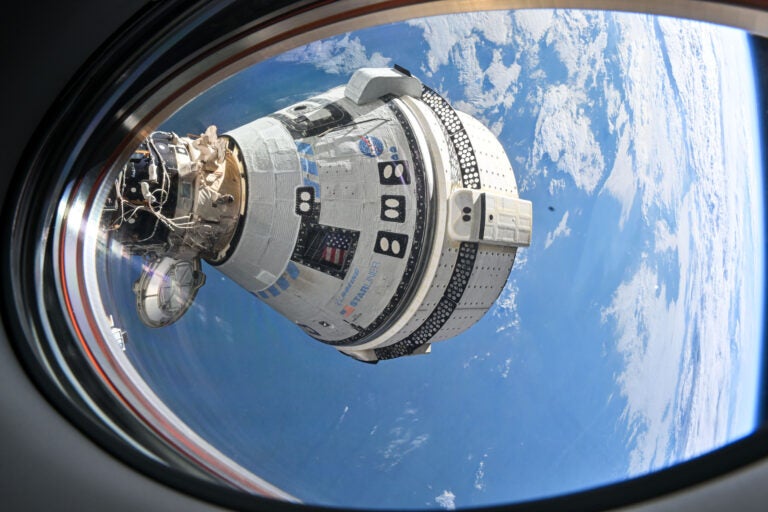

Current plans call for an uncrewed 57,000-pound (26,000 kilograms) Lanyue (Embrace the Moon) lander to be sent to lunar orbit by a Long March 10 rocket. The crewed Mengzhou (Dream Vessel), also launched by a Long March 10, will rendezvous with the Lanyue and the astronauts will descend to the surface in the lander. A rover with a 6-mile (10 km) range will allow extended exploration. After leaving the Moon, the crew will return to Earth aboard Mengzhou. Subsequent Chinese plans include establishing a basic Moon base by 2035, expanding to a lunar station by 2045 in partnership with 10 other nations.

India is now a spacefaring power and also has ambitious lunar plans. India’s 2008 Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter provided convincing evidence of water ice on the Moon. A lunar landing attempt in 2019 failed, but in August 2023, the Vikram lander successfully touched down and deployed the Pragyan rover near the Moon’s south pole. The achievement marked India as the fourth nation to land on the Moon. India’s plans for a crewed lunar landing in the 2040s are in their early stages, but India possesses the technology to accomplish that goal.

Japan became the fifth country to land on the Moon when its Small Lander for Investigating the Moon (SLIM) made a precision landing near Theophilus Crater in January 2024. Unfortunately, the lander came to rest nearly upside down, limiting the amount of power supplied by its solar cells. Two small rovers were successfully deployed, and SLIM remained in contact with Earth for two months (four lunar days).

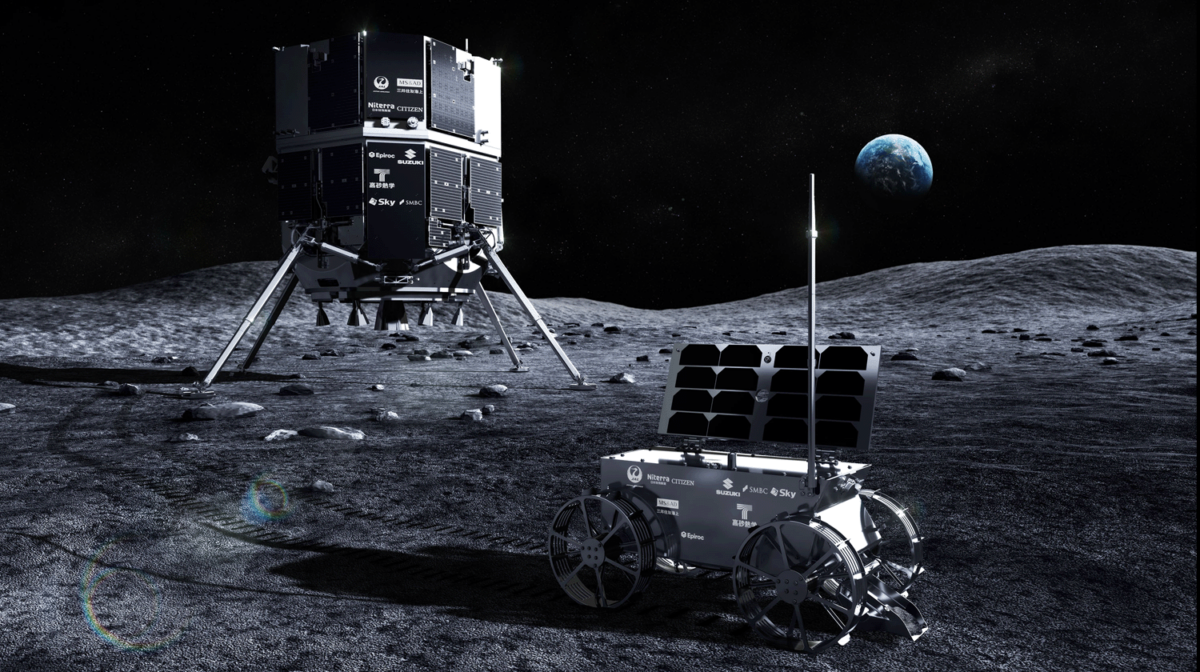

The Japanese company ispace is preparing its Hakuto-R Mission 2 carrying the Resilience lander and Micro Rover for an early 2025 launch. Additionally, Japan is partnering with India for the joint Lunar Polar Exploration (LUPEX) project. Japan will provide a Mitsubishi H3 rocket to propel the Chandrayaan-4 lander to the Moon in 2026 where it will deploy a 770-pound (350 kg) rover carrying NASA and ESA instruments to search for ice at the lunar south pole. After the cancellation of NASA’s VIPER rover, LUPEX is the next opportunity to use a rover-mounted surface drill and spectrometer to search for ice in the Moon’s shadowed south polar region.

Risk and reward

Not every mission on this new lunar frontier is a success. The Israeli Beresheet (In the Beginning) lander — attempting the first lunar landing by a private company — suffered an engine problem and crashed in April 2019. (Undeterred, Beresheet 2 is scheduled for flight in 2025.)

In December 2022, Japan’s Hakuto-R Mission 1 lander crashed on the Moon when a software fault resulted in the craft hovering 3 miles (5 km) above the surface until it ran out of fuel.

And the Russian Luna 25 lander — attempting to pick up the torch from 1976’s Luna 24 — impacted the Moon in August 2023 when an orbit-lowering burn lasted longer than commanded.

Both the successes and failures recall President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 declaration that we accept challenges like going to the Moon “not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.” The ongoing surge of interest in lunar exploration represents a new global wave of energy and skill — and scientists and space aficionados the world over will be its beneficiaries.