Earth’s Moon looms large in our future

There is a new space race, just as consequential as the 20th-century competition between the United States and the former Soviet Union, set in motion when that nation hurled Sputnik into orbit in 1957.

It’s been six decades since that polished artificial moon circled our planet. It weighed all of 184 pounds—and it beeped. Those transmissions sent technological, scientific, and political shock waves not only throughout the United States but around the globe.

Emerging out of the space race rivalry between the Americans and the Soviets was a new federal agency: NASA, established in 1958 to develop the technological wherewithal to make new and unprecedented leaps in exploration and discovery.

The space race became a fierce, competitive contest. The starting gun had been fired, and the finish line was the Moon.

The result: America’s Apollo program. It was a grand team effort, tapping into the talents of 400,000 people who bonded together to make a vision come true. It was a unified undertaking, a melding of governmental, industrial, and academic talents, all absolutely necessary to accomplish what President John F. Kennedy challenged us to do: send our people safely to the Moon’s surface and back by the end of the 1960s.

Rocket forward 50 years

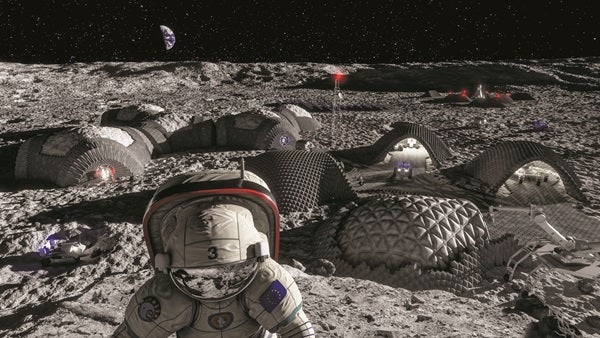

The Moon of tomorrow is being crafted today by visionary scientists, engineers, designers, and entrepreneurs from around the world, working together in a dynamic relationship. At the same time, governments, private industry, and regulatory agencies are seriously considering matters of off-planet politics, economics, and law—exchanges that are influencing the plans and aspirations for a human return to the Moon.

Thanks to the Apollo lunar landing program and ongoing surveys by robotic craft since then, we know our Moon to be a treasure trove of resources. Basic geologic prospecting still needs to go on. If shown to be rich in resources, the Moon can be brought into Earth’s economic sphere of influence. Given the Moon’s other assets—solar energy, extractable water, and especially the distinctive places on the lunar surface best suited for establishing a base of operations—discussions of the legal framework for divvying up the Moon are sure to become heated as for-profit enterprise and other forms of governance establish their lunar foothold.

As the Moon harbors very little atmosphere, it could become a hub for gathering solar energy, collecting and then beaming power from the lunar surface to Earth and other destinations in space. Some also consider the Moon a ready repository of helium-3 that could be harvested into a clean and efficient form of energy.

Astronomers have already blueprinted lunar-situated telescope farms and radio dishes, to be planted on the far side of the lunar surface, where such a facility would be shielded from Earth’s broadcasting pollution. Building a telescope on the Moon, using innovative techniques like 3D printing using lunar soil as the main material, would enable us to look more deeply into the universe.

There is rising worldwide interest in Moon exploration—it’s not just an American endeavor. Other nations, particularly China, are developing long-range lunar exploration plans. The European Space Agency (ESA) is poised to work with multiple nations to establish a “moon village,” an international collaboration among spacefaring nations resulting in a base for science, business, mining, and even tourism. Other countries, too, are crossing the intervening void between Earth and our neighbor, making plans to image, survey, land upon, and help sustain a lasting foothold on the Moon.

The Trump White House and Vice President Mike Pence are shaping a new U.S. space strategy, one that squarely puts American interest in the Moon first, together with a policy of using government and private skills together to eventually reach the “horizon goal” of sending humans to Mars.

As signed by President Trump, Space Policy Directive 1 underscores the need for reinvigorating America’s human space exploration program. That signature policy statement calls upon NASA to “lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities. Beginning with missions beyond low-Earth orbit, the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations.”

Indeed, affirming America’s back-to-the-Moon commitment is the bold goal announced by Pence in March 2019 of landing humans on the south pole of the Moon in the next five years.

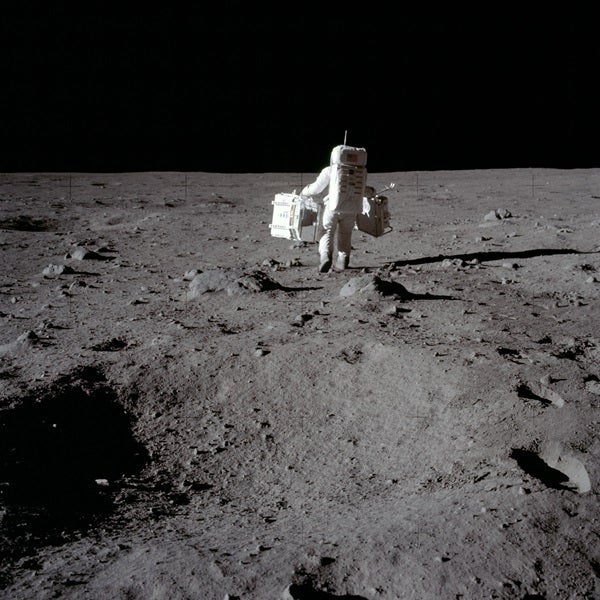

Fifty years ago on July 20, 1969, humankind made first footfall on another celestial body and into history. Mission Commander Neil Armstrong took this image of Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin, as he deployed scientific gear at Tranquility Base in our Moon’s Mare Tranquillitatis, or Sea of Tranquility.

All that said, whether the next wave of Moon interest can be sustained in “stay, survive, and thrive” mode remains to be seen. There are those who picture a future when the Moon tosses off an extra-added glow in the nighttime sky, when we on Earth will be able to behold visible lights shining out from a sparkling, sprawling lunar city as humanity acquires a long-lasting grip on our close-at-hand world.

Predicting what a permanent human presence on the Moon will look like is tricky.

Nevertheless, as reflected in a Chinese proverb, “The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.” On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made the first historical steps onto the lunar landscape … and there are many more to follow.

But now the question for America, with our aspirations of returning humans to the Moon, is whether we are destined this time to stay … or to stray from a constancy of purpose.

Space journalist Leonard David is the author of Moon Rush: The New Space Race, published by National Geographic in May 2019.