A European spacecraft zipped by both Earth and the Moon last week. In the early 2030s, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission will be the first European probe to orbit Jupiter. But first, it had to to carry out a key maneuver to help set up its eventual encounter with the giant planet.

JUICE flew past the Moon at 22:16 BST on August 19. It then zipped by Earth on August 20 at 22:57 BST.

It’s now 16 months since JUICE launched from Europe’s spaceport in French Guiana. Its flyby of Earth and the Moon made JUICE the first ever spacecraft to attempt a lunar-Earth gravity assist maneuver, or LEGA.

During the ambitious sequence of maneuvers, JUICE exploited the gravitational attraction of both the Earth and the Moon to alter its trajectory and emerge at the end of the sequence on a new course that will set up a third planetary encounter with Venus in August 2025.

At Venus, JUICE will undergo a slingshot maneuver back to Earth (twice) and finally on to Jupiter where it will enter into orbit in July 2031 to start a three-and-a-half-year mission to explore the giant planet’s icy moons, Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa – together with the volcanic satellite Io, these are known as the Galilean moons, after the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei.

Such a scenic route offers unique opportunities for close-up views of distant worlds as well as for calibrating instruments that will be mapping out Jupiter’s environment and studying the three moons where – scientists believe – alien life could be discovered in their sub-surface oceans. Measurements indicate that Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto all have liquid water beneath their outer shells and scientists believe it’s possible alien life could have developed there.

Pragmatic decision

The first LEGA maneuver is the only way by which the spacecraft will be able to carry its 617 pounds (280 kilograms) of scientific instruments to Jupiter with enough propellant left to enter orbit around the planet and execute its exciting mission.

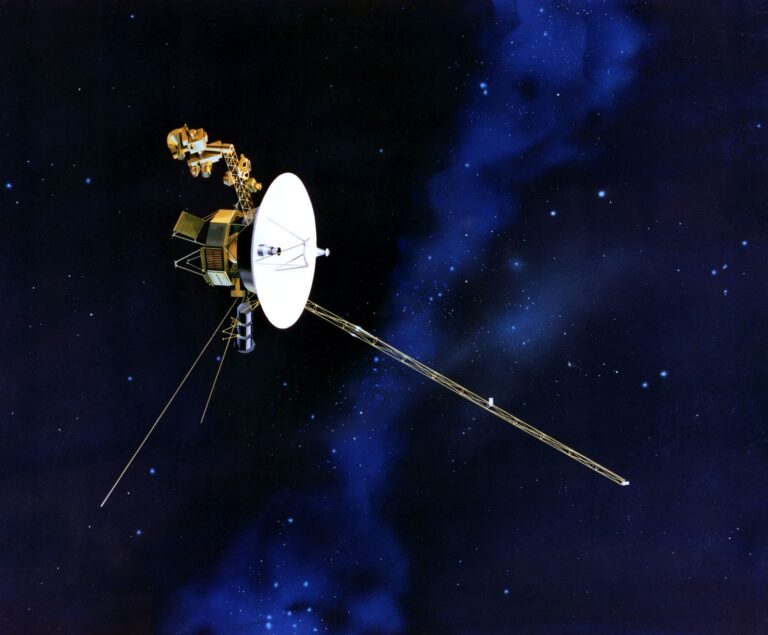

The fuel savings are so vast that gravity assist maneuvers have been used since the dawn of space exploration, enabling missions such as Voyager 1 and 2. These spacecraft were launched in 1977 to study the outer planets, but have since traveled into interstellar space – the space between individual stars. These spacecraft are now the furthest human-made objects from Earth and have completely revolutionized our understanding of the solar system.

What makes the LEGA of August 19 and 20 so special is that never before has there been a need to implement two gravity assists within the short timespan of a single day.

But on August 19, the Moon happened to be in the perfect spot for altering the trajectory of JUICE in such a way that its subsequent Earth flyby was as efficient as possible in catapulting the spacecraft towards Venus.

This has the advantage of ultimately reducing the total time the spacecraft would need to reach Jupiter (still no less than eight years). However, it also comes with more severe trajectory and operations requirements that will test the most skilled and experienced mission operators on Earth.

Flying by a planet or moon is no easy feat. Mission designers and spacecraft operators must meticulously plan the timing, distance and flight direction for each of the planetary encounters. The spacecraft must then follow each of these instructions on an accurate and timely basis.

This is complicated by limited knowledge of the spacecraft position and velocity in three-dimensional space (usually with an accuracy of a few miles and a few inches per second, respectively) as well as by sophisticated, yet imperfect, models of the space environment that hinder our ability to accurately predict the orbit of a spacecraft beyond a few days.

But if deviations from the nominal flight path are seen to become too large, the spacecraft engines are switched on to reduce the error as much as possible. Make a mistake or let the error grow too much, and your mission can be lost in space.

The margin for error is even smaller when flying by two planetary objects in a rapid sequence, as JUICE did. With less than 24 hours between the Moon and Earth flybys, there was very little time to react to problems. That is why mission planners at the European Space Agency (ESA) have a network of ground stations around the world that use giant telecommunications dishes to communicate with spacecraft. They constantly monitored, measured, estimated, and corrected the trajectory as much as they could for the two days on either side of the close encounters.

During this time frame, international teams of spacecraft operators worked around the clock to analyze the data beamed down by the spacecraft and keep it on course with tiny adjustments.

There are ten science instruments on the spacecraft, alongside navigation equipment, that collected data during the Earth and Moon close encounters to verify that the trajectory was on track.

Data from JUICE will be returned to Earth via two antennas on the spacecraft of different sizes. But JUICE will need to point very accurately back to Earth to deliver the vital science and navigation data.

The maneuvers enabled Juice’s encounter with Jupiter in 2031 and the beginning of its mission of exploration. There’s the exciting prospect of observing icy moons that are considered some of the most promising places in the solar system to look for extra-terrestrial life. This could shed further light on conditions under the outer ice shell and how hospitable they might be to living organisms.

The spacecraft will also be gathering data on Jupiter itself, which is the solar system’s biggest planet and holds many secrets that are yet to be unlocked. The pay-off from the Earth-Moon flyby on August 19 and 20 was huge, setting up a new frontier in the exploration of planets and their moons.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.