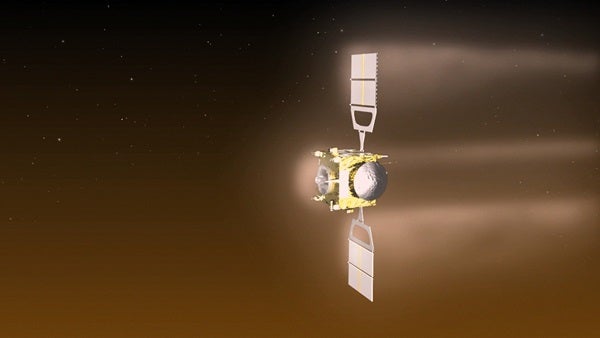

The polar atmosphere of Venus is thinner than expected. How do we know? Because the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Venus Express has actually been there. Instead of looking from orbit, Venus Express has flown through the upper reaches of the planet’s poisonous atmosphere.

Venus Express went diving into the alien atmosphere during a series of low passes in July-August 2008, October 2009, and February and April 2010. The aim was to measure the density of the upper polar atmosphere, an experiment that had never been attempted before at Venus.

The campaign has returned 10 measurements so far and shown that the atmosphere high above the poles is a surprising 60 percent thinner than predicted. This could indicate that unanticipated natural processes are at work in the atmosphere. Ingo Mueller-Wodarg from Imperial College, London, and his team are currently investigating.

The density is critical information for mission controllers, who are investigating the possibility of driving the spacecraft even lower into the atmosphere in order to change its orbit and extend the lifetime of the mission.

“It would be dangerous to send the spacecraft deep into the atmosphere before we understand the density,” said Pascal Rosenblatt from the Royal Observatory in Belgium.

The fact that Venus Express can make these measurements at all is remarkable. The spacecraft was not designed for it and so does not have instruments capable of directly sampling the atmosphere. Instead, radio tracking stations on Earth watch for the drag on the spacecraft as it dips into the atmosphere and is decelerated by the venusian equivalent of air resistance.

In addition, operators at ESA’s European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, turned one solar wing edge-on and the other face-on so that air resistance would twist the spacecraft.

Venus’ atmosphere extends from the surface up to an altitude of around 155 miles (250 kilometers). During April, Venus Express briefly skimmed down to 110 miles (175 km) above the planetary surface.

As well as the surprisingly low density overall, the twisting of the spacecraft has also registered a sharp density change from the day to the night side of the planet. Next week, Venus Express will go diving again, this time to within 100 miles (165 km) of the surface.

These measurements may also be used eventually to help make changes to the orbit of Venus Express, halving the time it takes to circle the planet and providing new opportunities for additional scientific measurements.

The current elliptical orbit takes 24 hours to complete and loops from 155 miles (250 km) to 41,000 miles (66,000 km). When Venus Express is far from the planet, it is pulled off course slightly by the Sun’s gravity. So, every 40-50 days, its engines must be fired to compensate. The fuel to do this will run out in 2015 unless the orbit can be lowered using the drag of Venus’ atmosphere to slow the spacecraft. It is a delicate, potentially dangerous operation and cannot be rushed.

“The timetable is still open because a number of studies have yet to be completed,” said Hakan Svedhem from ESA’s Venus Express. “If our experiments show we can carry out these maneuvers safely, then we may be able to lower the orbit in early 2012.”