Early on July 31, 1999, human eyes fastened with rapt eagerness on the Moon’s south pole as a spacecraft plunged to its demise in a breathtaking bid to uncover whispers of water on a parched world. Although Lunar Prospector was quickly snuffed out in a shadowy crater, it ignited a search for the building blocks of life on our celestial neighbor for years to come.

Its 18-month voyage to Earth’s only satellite uncovered a place with the potential to host colossal reservoirs of water ice at its poles, hinted at an iron-rich core, and pinpointed a measly magnetic field. “A voyage to rediscover the Moon,” was how NASA commentator George Diller described it as Lunar Prospector launched into the darkness above Cape Canaveral, Florida, atop an Athena II rocket at 9:28 P.M. EST on Jan. 6, 1998.

Diller was right. Over two decades since the last man left his bootprints in lunar dust, the Moon’s uniqueness was amply recognized, but its geological lifelessness was very much taken for granted. Yet as the Apollo astronauts forever altered the Moon’s image, Lunar Prospector would do so again.

Mission blueprints

Lunar Prospector rose from the drawing board of NASA’s low-cost Discovery Program, a campaign to explore space with missions priced at less than $150 million — a fraction of multi-billion-dollar flagship ventures like the Viking Mars landers, the Galileo Jupiter orbiter, and Voyager’s half-century-and-counting grand tour of the outer solar system. The final price tag for Lunar Prospector came in at a comfortable $62.8 million.

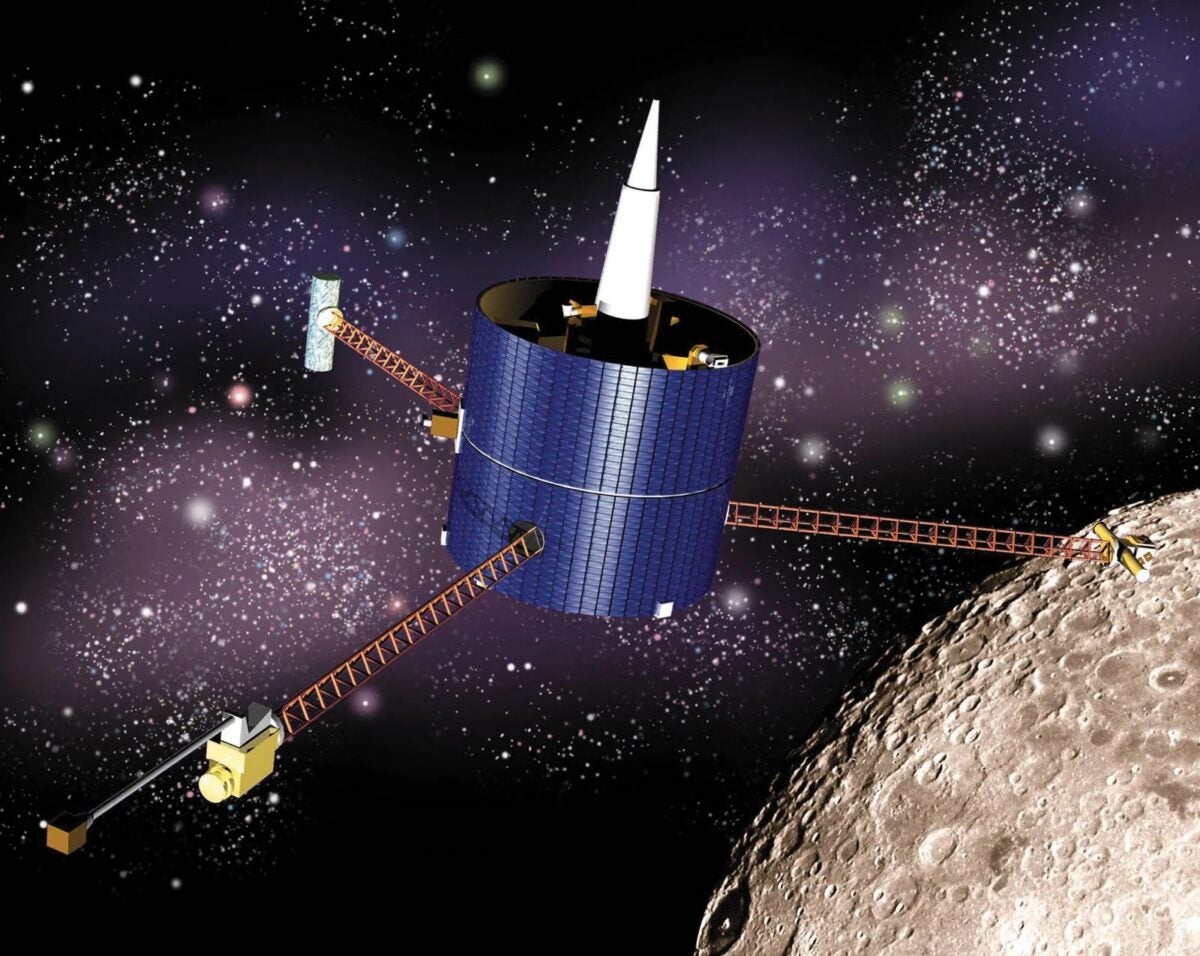

Entering development in 1995, the project targeted a 1997 launch for a polar-orbiting lunar mission to map the Moon’s surface composition, assess possible water-ice deposits, and characterize its magnetic and gravitational fields. Built by Lockheed Martin, the drum-shaped probe bristled with three equidistantly spaced instrument booms, each measuring 8 feet (2.5 meters) in length.

Six instruments — an electron reflectometer, magnetometer, gamma-ray spectrometer, neutron spectrometer, alpha-particle spectrometer, and Doppler gravity experiment — would globally scour a world whose 14.6 million square miles (38 million square kilometers) equate to a total land area slightly less than Asia.

Before Lunar Prospector, less than 25 percent of the Moon had been mapped in detail. And key questions about its origin and evolution were a blank slate.

But hopes of a mid-1997 launch evaporated due to developmental issues. Further technical maladies with the Athena II rocket pushed the launch into January 1998.

After takeoff, Lunar Prospector took 105 hours — about four and a half days — to travel the 240,000 miles (370,000 km) between Earth and the Moon. It slipped into an initial “capture” orbit on Jan. 11. It then gradually shaved its orbital period from 11.6 hours to just under 2 (118 minutes, to be exact) before entering into a polar “mapping” orbit that carried it just 62 miles (100 km) above the rugged lunar terrain.

A year of discoveries — and surprises — had begun.

Identifying H2O

By March 1998, Lunar Prospector had already tentatively identified water ice in permanently shadowed craters near the north and south poles. It did so by revealing substantial hydrogen, assumed to be locked within water. The water signature was some 15 percent stronger at the north pole than the south. Hydrogen concentrations at the poles were also three times higher than the lunar average.

Early calculations estimated that about 300 million metric tons of water ice was locked in rock at the poles, but were later modified in September of that year down to 6 billion metric tons, buried in highly concentrated deposits beneath 18 inches (45 centimeters) of lunar regolith.

The floors of permanently shadowed craters never face the Sun and remain dark in some cases for more than 2 billion years. They tend to lie at high latitudes where the Moon’s axis is almost perpendicular to the direction of sunlight.

One such crater, named Shoemaker, is 51 miles (32 km) wide and resides east of the lunar south pole at 88.1° south latitude. Its antiquity is manifested in a heavily worn rim and dozens of tiny craters that scar its interior walls. Eternally dark, conditions at its floor never creep higher than -343 degrees Fahrenheit (-173 degrees Celsius).

Shoemaker at its deepest is 1.5 miles (2.5 km), enough to pile three skyscrapers the height of Dubai’s Burj Khalifa on top of one another. At these depths, so-called cold traps form on its ink-dark floor, where water molecules from comets or other impactors accrue and remain indefinitely.

With substantial hydrogen and water ice at both poles, the evidence was persuasive that the Moon could support human colonies. “The data do not tell us definitively the form of the water ice,” said Lunar Prospector Principal Investigator Alan Binder. “However, if the main source is cometary impacts … our explanation is that we have areas at both poles with layers of near-pure water ice.”

A deep dive

Lunar Prospector completed its baseline year-long mission in January 1999 and was then extended by m months. Its orbit was lowered to 25 miles (40 km) above the surface to gather higher-resolution data, and it was later lowered again to 9.3 miles (15 km).

As its mission drew to a close, a novel plan was crafted in which NASA would crash the probe into a permanently shadowed crater to test hypotheses that water ice indeed lay under the surface. When the probe crashed, researchers reasoned, buried water ice might be blasted into space and visible in the resulting plume. Shoemaker proved an ideal candidate: Its rim was tall enough to be permanently shadowed but low enough for Lunar Prospector to chart an approach and impact trajectory, hitting the crater’s floor with near-bull’s-eye precision.

The mission’s end and destination carried added poignancy, for aboard Lunar Prospector were the ashes of geologist Eugene Shoemaker, the crater’s namesake.

Although the odds of punching a hole deep enough into Shoemaker’s floor to release a plume rich with water ice were gauged at no better than 10 percent, the daring dive still captivated an earthly audience and seized international headlines.

At 4:52 A.M. EDT on July 31, 1999, Lunar Prospector hit the crater at 3,800 mph (6,100 km/h), garnering the briefest of flashes that was visible from Earth. Sadly, no water was detected, possibly because the probe missed its intended target point, impacted a rock, or simply hit a patch of dry soil.

Despite the lack of results, it did not deter scientists from trying again. In October 2009, the Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) hit Cabeus, a south pole crater, this time successfully revealing water-ice grains in the ejected material. Later, data from NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) aboard India’s Chandrayaan-1 probe confirmed water-ice patches are present in many permanently shadowed craters. And in late 2024, NASA’s PRIME mission will drill for ice at Shackleton Crater, which lies near Shoemaker at the lunar south pole.

This renewed interest in our closest celestial companion owes much to Lunar Prospector. Its short but eventful life teased us with the lure of water on a world previously written off as lifeless. And the Moon’s grip on humanity continues to resonate a quarter-century later as we prepare for our next grand adventure: returning to the lunar surface to stay.