The mission’s 16th flyby of the giant moon Titan occurs July 2, two years after the spacecraft’s first detailed glimpse of the giant moon. Aside from the smog-shrouded moon’s inherent interest to scientists, Titan is the only moon with enough mass to significantly alter Cassini’s trajectory, which makes the complex 4-year tour possible. Of the 44 Titan flybys planned for the probe, 13 occur in 2006.

When the spacecraft passes Titan on July 2, the moon is in an unusual position relative to the incoming solar wind (an interplanetary flow of charged particles), the Sun, and Saturn. For this reason, Cassini’s magnetospheric instruments will control the spacecraft’s targeting up to closest approach — one of only two flybys where this occurs. Cassini passes within 1,188 miles (1,911 kilometers) of Titan then. After closest approach, another set of instruments will probe Titan’s atmosphere in the infrared.

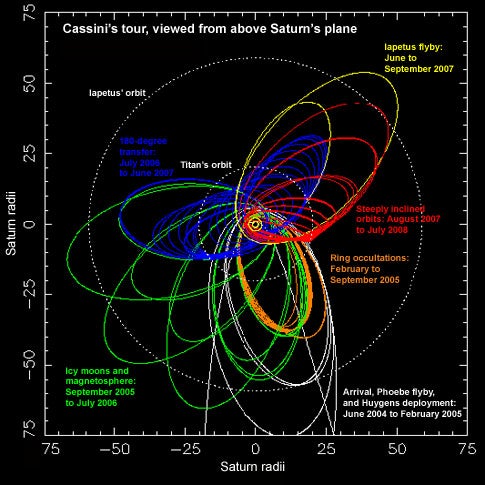

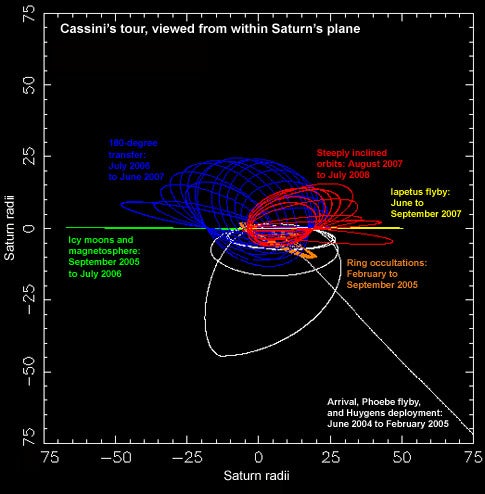

Cassini passes from south to north through the ring plane July 26, then crosses it in the opposite direction August 15. Two weeks later, on August 28, the craft will reach its greatest distance from Saturn (1.8 billion miles [2.9 billion km]) and begin its 28th orbit around the ringed planet.

From September 10 through 16, Cassini will view no less than six occultations of the Sun or Earth by Saturn or its rings. These long-duration events will yield information on the D and C rings unattainable at any other time in the tour. On September 17, Cassini whisks past Titan by just 620 miles (1,000 km).

October and November: October opens and closes with two more 620-mile-distant Titan flybys (October 9 and 25). Cassini comes within 76,000 miles (123,000 km) of Saturn’s moon Telesto on the 25th.

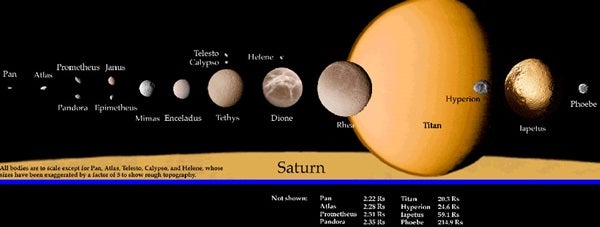

On November 9, Cassini speeds past the water-spewing moon Enceladus. Plumes of water and ice vent from fissures near the moon’s south pole, but this flyby gives the probe only a distant view from 77,700 miles (125,000 km) away.

December: Cassini’s December 12 close Titan flyby begins what mission controllers call “the 180° transfer.” Previous Titan passes have raised the inclination of Cassini’s orbit so it crosses Saturn’s equatorial plane at a steeper angle. This change enabled the probe’s “occultation season” and provided a better view of the rings. But now, controllers will use Titan’s gravity to relocate the farthest point in the spacecraft’s orbit. With each orbit, Cassini will delve deeply into Saturn’s magnetotail, the region of the planet’s magnetosphere stretched far behind Saturn by the solar wind. Cassini closes out the year with another Titan flyby December 28.

The big events for 2007 include another alteration to Cassini’s orbit. This time, the most distant part of the probe’s orbit will be rotated toward the Sun to allow observations of Saturn’s atmosphere at both great distance and at a low Sun-Saturn-Cassini angle. It seems counterintuitive to push the probe farther from Saturn, but scientists want to view the entire planet at once using Cassini’s narrow-angle camera. Cassini will be at its slowest orbital speeds around Saturn as it makes these observations. We can expect to see the mission’s most detailed movies of Saturn’s storms and cloud belts.

The push away from Saturn also affords Cassini another close flyby of the two-toned moon Iapetus. The craft will sweep within 620 miles (1,000 km) of the moon September 10. Iapetus ranks among the system’s oddest moons — dark on one hemisphere, bright on the other. Scientists suspect organic material splattered off neighboring moon Phoebe may explain the dark hemisphere, which leads Iapetus in its orbit. Again, Cassini’s relatively slow encounter speed ensures it will gather volumes of data on this curious satellite.

On October 2, just weeks before Cassini begins its 51st orbit, a close Titan flyby marks the start of another orbital change. This begins a series of 10 flybys designed to raise Cassini’s orbit to extreme inclinations.

Cassini’s closest satellite encounter of 2007 belongs to Epimetheus, one of two Saturn moons that swap orbits. The probe sweeps within 4,000 miles [6,000 km] of Epimetheus December 3.

In this last year of Cassini’s primary mission, Titan flybys continue ramping up the spacecraft’s orbital inclination to more than 75° relative to Saturn’s equatorial plane. From this perspective, Cassini will provide views of the ringed planet from nearly straight above Saturn’s poles. As if ending with a flourish, Cassini dives within 620 miles (1,000 km) of the active moon Enceladus March 12. The spacecraft’s primary mission ends July 1, after 4 years and 74 orbits around Saturn.

Informal planning for an extended mission has been going on since Cassini first arrived at Saturn. If the spacecraft stays healthy, it should have fuel and power enough for another year or more of exploration. Controllers might undertake riskier ring passages or closer moon flybys if given the chance. But it’s too early to predict whether NASA’s budget will be strained too tightly to fund extra time at the ringed planet.