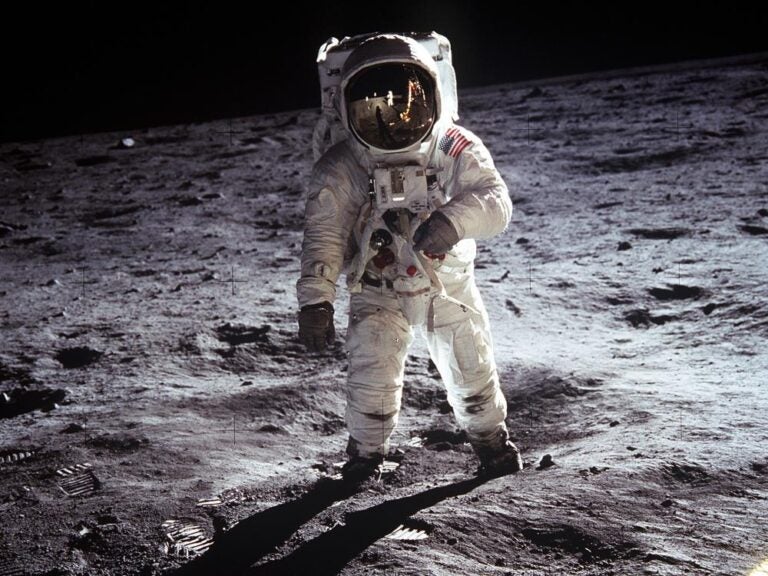

At the dawn of the space age, test pilots like these were snatching records from each other left and right, risking their lives to push aviation to speeds and heights unimaginable just 50 years earlier. And when the American space program was ready to start sending humans beyond the boundary of space, they trusted test pilots with the first pioneering missions into the final frontier.

These test pilots were said to embody “the right stuff,” as laid out in American journalist Tom Wolfe’s book of the same name. According to Wolfe, astronauts and test pilots at the beginning of the space race didn’t talk about fear or courage.

“Any fool can put his hide on the line and throw away his life in the process,” Wolfe wrote in the series of Rolling Stone articles he’d eventually base his book on. “The idea is to be able to put your hide on the line — and then to have the moxie, the reflexes, the talent, the experience, to pull it back in at the last yawning moment — and then be able to go out again the next day and do it all over again — and, in its best expression, to be able to do it in some higher cause, in some calling that means something.”

By the end of next year, these first private astronauts should begin launching into space on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule, the first-ever privately-owned spacecraft capable of reaching orbit. Meanwhile, an ever-growing list of other spaceflight companies are lining up to offer their own tourist trips to space.

Like the early wealthy adventurers who supported aviation in its infancy by buying pleasure rides in airplanes, these paying astronauts will help fund the technology to eventually make humanity a fully spacefaring species.

The requirements for spaceflight have changed, but early adopters should still expect to have plenty of “moxie,” even if they don’t have to worry as much about talent and reflexes. Private astronauts will also need to meet some basic medical requirements, which will vary depending on their space travel method of choice.

And while passengers on private spacecraft aren’t federally required to pass physicals, they are recommended by the FAA. The agency also says that paying ticket holders will also need to be trained in how to respond to emergencies, in case there’s a fire onboard or the cabin loses pressure. Spaceflight companies will also be required to get the “informed consent” of their customers.

“It’s somewhat akin to going to a doctor’s office,” Kelvin Coleman, the Federal Aviation Administration’s Deputy Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation, told Astronomy in 2019. “The doctor informs you of all the known risks associated with the particular procedure or operation, and once the patient has been informed of that, some documentation is signed and then the procedure proceeds. We ensure that consultation is made, and that documentation is in place before those space flight participants and crew members can fly.”

Regardless of the FAA’s light hand, anyone traveling to space is going to face certain physical challenges. The microgravity they encounter will physiologically change the human body, as NASA’s research has shown repeatedly over the years.

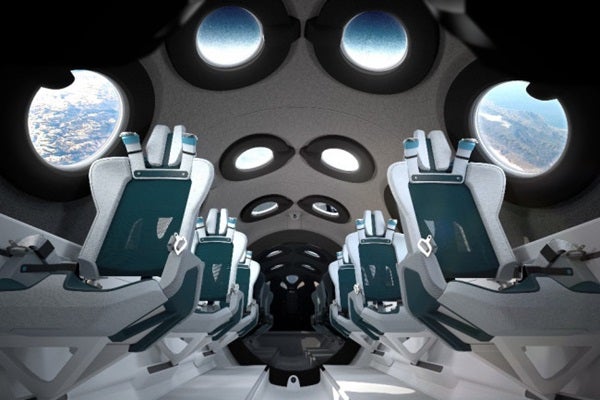

Space planes

Like Yeager’s legendary first supersonic flight, a new generation of test pilots — this time employed by the private spaceflight companies — are taking to the skies. At Virgin Galactic, a handful of pilots have now earned their commercial astronaut wings. But the effort hasn’t been without risk. In 2014, the VSS Enterprise crashed in the California desert, killing copilot Michael Alsbury and injuring pilot Peter Siebold.

In the past two years, however, the company has managed to fly two successful suborbital space flights. It also plans to conduct two additional test flight — gaining FAA certification in the process — before it puts Virgin Group founder Richard Branson into space early next year. After that, private space tourists on the waitlist will purchase their tickets for around $250,000 a pop.

And the company is optimistic about things to come over the next decade. Though Virgin Galactic only has one spaceport for now, the company says it will soon be making daily spaceflights from multiple sites, chiefly Spaceport America in New Mexico, according to reporting by CNBC. That kind of action would quickly involve sending thousands of tourists into space in coming years. And many of the first would be celebrities that are currently on the waitlist, including Tom Hanks, Leonardo DiCaprio, Angelina Jolie, Brad Pitt, Lady Gaga, and Justin Bieber.

Virgin Galactic itself lists relatively few requirements for astronauts on its website. And rather than issue firm regulations on private spaceflight, the FAA has largely taken a wait-and-see approach in hopes of not hampering the nascent industry’s progress.

So, instead of saying who can and can’t be a private astronaut, the FAA says it will let the private spaceflight industry regulate itself until something happens that necessitates a stricter approach. However, the FAA’s registrations do prohibit anyone under the age of 18 from flying. Virgin Galactic, meanwhile, has suggested its future astronauts run the gamut in age, ranging from teenagers to people in their 90s.

Before flying to the edge of space for the first time, these Virgin astronauts will get three days of prep and training at Spaceport America. Virgin Galactic says its training process will ensure every paying ticket holder can handle the trip, both mentally and physically. The training will also teach inflight safety.

“We will prepare every astronaut thoroughly, through a program of medical check-ups and tailored training,” the company says on its site.

Commercial rocket rides

In 1961, Navy test pilot Alan Shepard became the first American to fly to space. The entire journey was relatively brief and he never reached orbit. But his Mercury-Redstone capsule stayed in space for some 15-minutes before coming back to Earth.

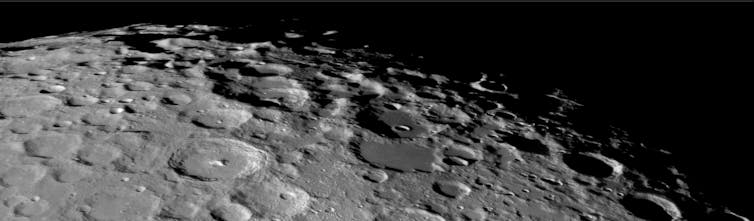

Now, as we usher in the dawn of the commercial Space Age, the modern day equivalent of Mercury-Redstone has already been built and tested by Jeff Bezos’ rocket company, Blue Origin. But instead of one cramped astronaut stuck without a view of the stars, Blue Origin’s suborbital capsule features room for six — and everyone gets a seat next to an oversized window. The cabin offers some 10 times more room than Shepard was provided.

Blue Origin’s New Shepard space capsule, named for Alan Shepard, has now gone through a battery of tests, successfully launching and landing a total of seven times. And soon the company plans to start offering trips to space aboard its suborbital rocket. New Shepard can launch its passengers to a height of roughly 62 miles (100 kilometers) above Earth’s surface, above the so-called Kármán line, which many define as the boundary of space. Earlier this year, Axios reported that Blue Origin could carry passengers as soon as this year. But COVID-19 has caused delays throughout the space industry.

Paying for a ticket to space might lead some to consider private astronauts “beneath” traditional NASA astronauts. But in reality, even some Americans viewed the earliest NASA astronauts as little more than trained monkeys, especially after the space agency chose chimps to pilot its earliest rockets. That view was never very accurate, though. The Mercury astronauts — not entirely unlike today’s soon-to-be pioneering private astronauts — faced the dangerous realities of flying in a relatively new and unproven spacecraft. Private astronauts might not have expert-level training, but they are still knowingly taking a risk.

For instance, even one of NASA’s earliest space chimps, Ham, had to show he had the right stuff after his Mercury capsule partially lost air pressure. This caused his ship to travel far higher and faster than NASA intended. Yet, despite the drama, Ham still managed to pull the lever he was trained to pull.

Trips to the Space Station

For their part, SpaceX, Blue Origin’s direct rival, is on track to start launching tourists to the International Space Station (ISS) in late 2021. SpaceX had two successful crew launches this year using its Crew Dragon spacecraft, and the capsule now has NASA’s certification to regularly ferry astronauts. But instead of handling all the tourism themselves, SpaceX is partnering with another spaceflight company, Axiom Space, to book Crew Dragon’s first private flights.

Ultimately, Axiom Space plans to build the world’s first commercial orbiting space station. But for now, they’ve booked three paying astronauts on a Crew Dragon flight to the ISS next fall. If it goes well, Axiom plans to send up to three paying crews to the ISS per year.

Booking a trip with Axiom reportedly costs upwards of $55 million, but that pricetag includes training, life support and medical support, provisions, and operations and mission management. Their training isn’t some token effort, either. Axiom supplies customers with a whopping 15 weeks of NASA-certified training designed to turn wannabe space tourists into astronauts. That pales in comparison to the years of work a NASA astronaut has to put in before venturing to space, but it’s exponentially more work than simply sitting through a safety presentation by an airline flight attendant.

So, who has the “right stuff” for private spaceflight? For now, at least, the answer is limited to those with plenty of money and reasonable health. However, these early space tourists are sure to be taking on some manner of personal risk.

But exactly how much risk? Only time will tell.