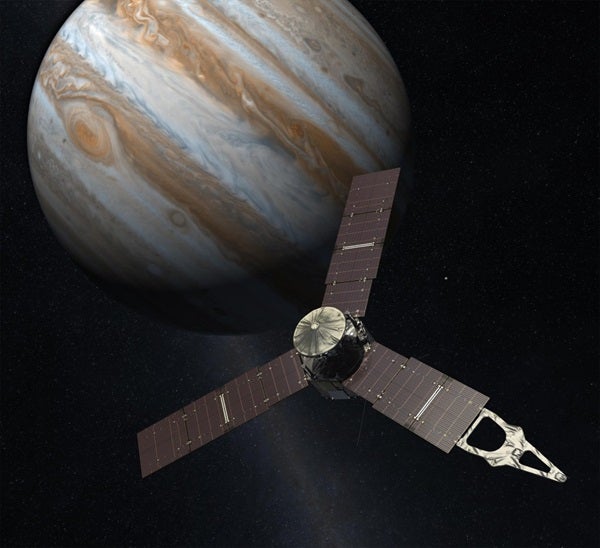

NASA’s Juno mission will arrive at Jupiter on the Fourth of July, after traveling some 1.7 billion miles through the solar system, and prepare to insert itself into orbit around the gas giant.

If everything goes smoothly, it will orbit the planet pole-to-pole 37 times, gathering data on Jupiter’s composition, magnetic field, core, poles and much more. And then, with its mission over, it will point itself at the planet and dive to a fiery death within the churning maelstrom that is Jupiter’s upper atmosphere.

Unlike some of its space-exploring brethren, the Juno probe is not meant to wander ever further into interstellar space, or lie dormant on the surface of a distant planet, generating data years after its mission is over. Instead, Juno takes a more rock n’ roll approach to life, living fast and hard and burning out before it has a chance to fade away.

This is the end

Juno’s life is set to end on February 20, 2018, just over a year and a half from now. Jupiter’s massive gravitational pull is too strong for the craft to overcome with its limited fuel supplies, says Scott Bolton, the principal investigator for the mission. Instead, its boosters will set a course allowing its orbit to rapidly decay over the span of five and a half days, setting it on a collision course with the planet.

Once there, according to Bolton, the drag from the atmosphere will cause the craft to heat up and eventually burn away. Juno will continue to send data as long as it can, much like the recent Venus probe, but once it enters the atmosphere, the drag will likely tumble the craft enough that the high-gain antenna will no longer point toward Earth, rendering the spacecraft mute.

Allow no contamination

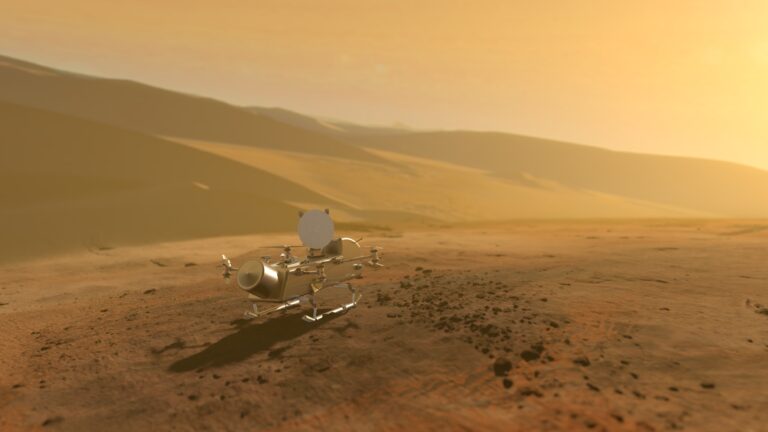

Sending Juno on a suicide mission also eliminates the probability, however slim, that it could crash into one of Jupiter’s moons and contaminate the environment with microbes Earth. Some extremophile organisms are capable of surviving in space for extended periods of time, and the investigators can’t be sure that some didn’t hitch a ride on the spacecraft. Introducing them to a foreign planet could theoretically have catastrophic consequences for any life that might be there — especially on Jupiter’s moon Europa. The icy moon is one of the best candidates in the solar system to search for life, because it’s likely home to vast, hidden oceans.

NASA takes significant precautions to avoid contaminating other planets — the Mars rover team last year was debated whether to study water flows on the planet’s surface, given the possibility of introducing Earth microbes to the environment.

Spacecraft are usually prepared in a sterile environment, but researchers can never be totally sure that there are no microbial hitchhikers present. The dual questions of what to do should we discover life on another planet and whether we should colonize other planets is hotly debated and deeply convoluted, and NASA is doing its best to avoid any harmful contact.

That’s why NASA has decided to let their $1.1 billion spacecraft crash and burn.

This post originally appeared on Discover Magazine