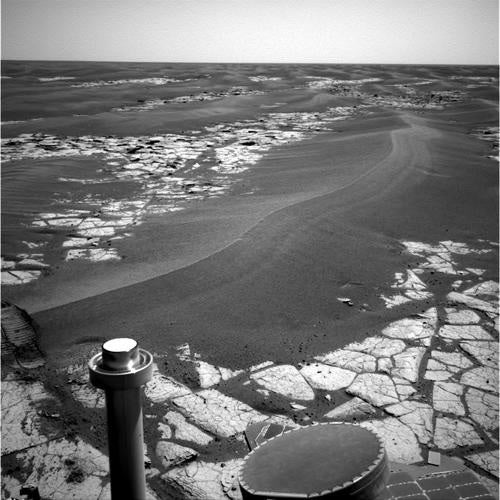

With temperatures plummeting on Mars, the twin rovers Spirit and Opportunity have been literally racing for survival. The heart of martian winter is less than 100 days away, and time is short for the intrepid robots to find safe havens. During winter, the rovers must be positioned on north-facing slopes for their solar panels to glean the most energy possible from the diminished winter sunlight.

The situation is most critical for Spirit, which lies 12° farther south than its near-equatorial sibling. Spirit now receives only enough solar power for daily drives of about an hour on flat terrain. But Spirit is not on flat ground. The rover has been scaling the Columbia Hills, hitting steep slopes and soft sand, since July 2004.

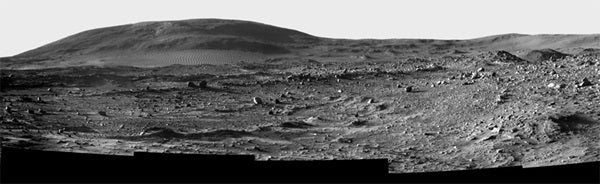

For the past several months, Spirit has been traversing a plateau called Home Plate. The site has signs of an explosive origin, like a volcano or impact. But despite Home Plate’s scientific value, engineers knew they must reposition the rover if it is going to survive winter. Operators mapped a route to a north-facing slope, but Spirit was unable to climb the terrain.

“There was a time when we were concerned [about reaching] a safe haven in time,” says John Callas, project manager for the Mars Exploration Rovers. But one of Spirit’s motors has now failed, leaving the right front wheel paralyzed. “When the wheel failed on us, the terrain turned out to be too difficult, so we had to choose a closer ridge,” he says. The rover retraced its steps and then headed toward the second site.

Both rovers are also showing signs of age. Each wheel motor has turned 13 million times, carrying the rovers 11 times as far as planned. The duo has returned 150,000 images, but there has been a price. Opportunity’s instrument arm has jammed in certain positions. Spirit’s rock grinder is worn out. And because of the failure of one of Spirit’s wheel motors, the rover must negotiate the rugged landscape while dragging the useless wheel, which is locked in position.

Scientists hope the rovers will be able to continue extensive research. Callas says Spirit is scheduled for “a very ambitious winter campaign,” including taking detailed panoramas using all 13 imaging filters. Spirit is also slated to brush away layers of soil and measure the material’s properties at different depths. In addition, the rovers will study winter clouds and their surroundings’ thermal properties.

Callas likens Spirit’s stationary science to the winter activities of American pioneers: “After harvest, they’d settle down to catch up on fixing furniture and quilting. Spirit’s winter campaign gives us an opportunity to catch up on all the science we’ve been putting off.” If the rovers can survive a second winter, their rich scientific return may continue for months or years.