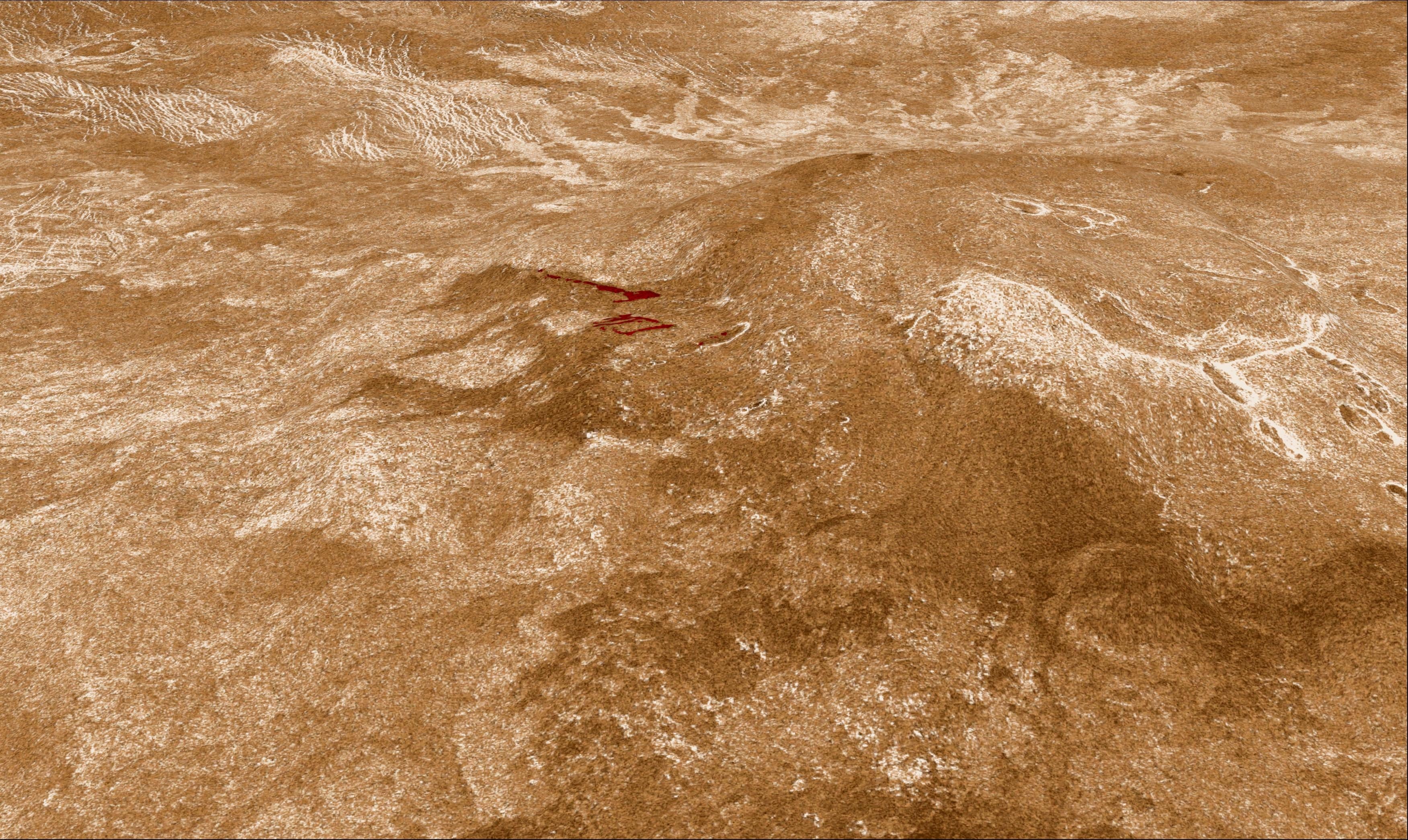

In a recent study, published in Nature Astronomy, a group of planetary scientists at Università degli Studi “G. d’Annunzio” in Pescara, Italy and Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza” in Rome, Italy, discovered geologically recent volcanic activity on Venus. The scientists combed through radar data collected by the first spacecraft to image the entire surface of Venus, Magellan, and compared data taken between 1990 and 1992 to confirm the presence of volcanism.

Essentially, these Magellan radar images revealed indications of lava flow reshaping the terrain at various sites on Venus. Scientists have been building an emerging picture of Venus as an active world, however, the tools needed are limited because Venus has only been studied by one spacecraft ever since Magellan dove into Venus’s atmosphere and went offline in 1994 — the evidence has only slowly accumulated using archival data.

The planetary scientists searched for radar backscatter (or, the reflection of more diffuse radar data traveling back to Magellan), to find areas of recent lava flows. Not only did they complete their goal of finding recent lava flows, but they may have discovered active volcanic activity.

(Watch below: This video highlights the areas of Sif Mons and Niobe Planitia on Venus where ongoing lava flows have been detected.)

“Interestingly, our analysis revealed significant increases in radar backscatter in two different areas: the western flank of Sif Mons, a broad shield volcano, and the western part of Niobe Planitia, a lowland area characterized by numerous shield volcanoes,” Davide Sulcanese of Università d’Annunzio, lead author of the study, says. “These changes are most likely due to new lava flows that occurred during the Magellan mission, providing evidence of ongoing volcanic activity on Venus.”

The Venus high-viscosity trap

The magma on Venus can also be basaltic, almost like Earth but not quite — Sulcanese says there are a number of differences between the magma on both planets. These differences are often driven by the lack of plate tectonics on Venus, resulting in more frequent volcanoes across the planet somewhat randomly. It also means many volcanoes are direct plumes from Venus’s mantle.

Where Venus is particularly dry, most water has been driven out of the planet, which also means the magma will be especially viscous. The volcanoes “tend to be more effusive than explosive, due to the low viscosity of basaltic lava and the lack of water in the magma.”

Related: Why did Venus turn inside out? | New research explains what happened to all the water on Venus

Venus has several shield volcanoes that are larger (reaching hundreds of kilometers) but less steep than the volcanoes on Earth. The planet also has numerous sites with elliptical patterns surrounded by crown-like rough terrain, known as coronae. The coronae are likely formed from mantle plumes, and pancake domes (large volcanoes stretching out several kilometers and a few kilometers high). Once the magma erupts from these volcanoes, the lack of strong winds leads to low erosion rates — with many existing relatively intact from formation, save a slight breakdown from sulfuric acid over time.

The volcanoes have consequences for Venus’s thick, hazardous environment.

“Volcanic activity releases gasses into the atmosphere, contributing to the planet’s thick atmosphere and extreme greenhouse effect,” Sulcanese says. “The dense atmosphere, composed mainly of carbon dioxide with clouds of sulfuric acid, traps heat and leads to surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead.” Moreover, this resurfacing means Venus has a relatively low amount of craters, ensuring Venus stays hellish.

Further understanding of Venus’s volcanism could come soon. Later this decade or early next, NASA plans to launch two important missions to Venus, VERITAS and DAVINCI+. VERITAS will take a wealth of radar data, while DAVINCI+ with drop a probe down toward Venus to examine the planet in infrared bands.

“These missions will offer comprehensive data on Venus’s volcanic processes, enhancing our understanding of terrestrial planets formation and evolution,” Sulcanese says.

In the meantime, scientists will have to rely on archival data to make new discoveries about our tempestuous sister planet.