Black holes are the darlings of science and science fiction. They were conceptualized as early as 1783 by English natural philosopher John Michell, who proposed “dark stars.” He envisioned stars whose gravity was so strong that they collapsed on themselves and nothing, not even light, could escape.

But the ironclad evidence for black holes was a long time coming. The first suspected black hole was Cygnus X-1, a system involving what was believed to be a black hole as a member of an x-ray binary system. Famously, in 1974, leading black hole theorists Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne playfully made a bet, Hawking betting against its confirmation as a black hole and Thorne for it. The evidence was a long time coming: finally, in 1990, Cygnus X-1 was confirmed as a black hole and Thorne won the bet.

The 1990s transformed into a boon for black hole discoveries. It soon became clear that several types of black holes exist, or must exist. The most abundant type must be stellar black holes, like Cygnus X-1, that form from the deaths of massive stars. These stellar black holes must exist in the millions even in our Milky Way Galaxy, but they are very hard to find. Detecting them involves favorable circumstances and their involvement with other, luminous objects, as in a binary system. We still know of only a couple dozen in our own galaxy.

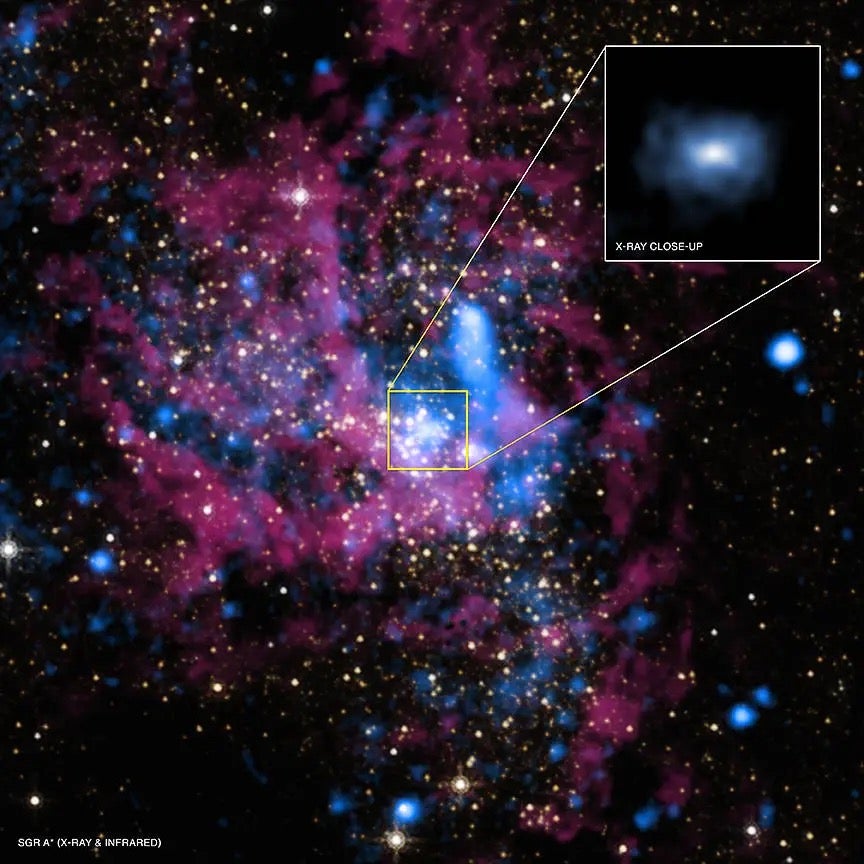

Soon, however, commenced an explosion of discoveries of another abundant type: supermassive black holes. These form at the centers of most galaxies, and they range from millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. The Hubble Space Telescope uncovered evidence of countless supermassive black holes, and we know that one, Sagittarius A*, exists in the center of our own Milky Way.

Based on their understanding of the early cosmos, astronomers also believe that primordial black holes emerged soon after the Big Bang, some 13.8 billion years ago. These are tiny black holes that may have been the size of an atom. The smallest primordial black holes have doubtless evaporated, but larger ones may still exist.

And in recent times evidence has emerged for a fourth class, so-called intermediate-mass black holes. These objects range from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of solar masses, and evidence for a small number of these objects is emerging. They may form in unusual cosmic areas, such as environments crowded with stars, from mergers of stellar black holes, or from some other phenomena.

Early on, the idea of a black hole captured the imaginations of writers. As regions of space with such strong gravity that nothing can escape, not even light, they are irresistible as objects of speculation: What would exist within a black hole? What would happen if a spacecraft approached a black hole? And perhaps the ultimate question, could a person survive traveling into a black hole?

The question becomes even more intriguing with the allied concept of a wormhole, a mathematical possibility that has not yet been proven to exist. The idea is that some black holes could be connected in space and time, leading to the idea of a wormhole – a tunnel, if you will – that hypothetically could make traveling across very large distances possible. And other types of wormholes, these space-time tunnels, could exist, unrelated to black holes.

But mathematical possibilities and logistical realities in the cosmos are often two different things. Put simply, the idea of surviving a black hole is quite naïve. Mind you, the gravitational forces when one would enter the event horizon, the boundary of a black hole, are quite different depending on the type. A stellar black hole would pull you into a kilometers-long string of protons as you approached it, thereby making the question of survival irrelevant. But the gravitational forces at the event horizon of a supermassive black hole are much less. You might enter a supermassive black hole without even knowing it.

That’s not the end of the story. Within any black hole is the central point, the singularity, which has infinite gravity and where mass is compressed into an infinitely small point. There, it is game over. There’s no surviving.

And therefore the idea of traveling through time and space, via black hole or wormhole, don’t really register in reality. “Whenever one tries to make a time machine,” wrote Hawking, “and no matter what kind of device one uses in one’s attempt (a wormhole, a spinning cylinder, a “cosmic string,” or whatever), just before one’s device becomes a time machine, a beam of vacuum fluctuations will circulate through the device and destroy it.”

So much as we love to read about black holes in science and science fiction, and imagine superpowers to use them as gateways to travel the cosmos, the hard reality says that we could do no such thing, and that falling into one would result in a very brief final chapter to anyone’s existence.

Editor’s note: This article was first published in 2023 and has been updated with NASA’s new visualization.