Before Clyde Tombaugh’s incredible find in 1930, our solar system was neatly divided into two regions. There were the terrestrial planets like Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, and then there were the gas giants of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. After Neptune, at about 30 astronomical units (1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance), the planets abruptly ended.

Then Pluto came along. It was alone and different — too small to fit the typical planet categories and slowly advancing in an oddball orbit. Scientists don’t like oddballs. Following his find, Tombaugh himself spent years at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, making sure there was nothing else as bright as Pluto out there undiscovered.

But decades later, Pluto was still raising a few astronomers’ suspicions that a third realm might lurk unseen at our solar system frontier. The then ninth planet’s oversized moon, Charon, implied that the system formed when two Plutos collided — an occurrence only likely if many more small planets also shared a similar orbit. And Neptune’s large, icy moon, Triton, similarly only made sense as a captured Pluto.

This prompted Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado and the current head of NASA’s New Horizons mission, to publish a bold suggestion in 1991. At some point, Stern said, there had to have been an unseen third realm of planets past Neptune that was home to 1,000 Plutos. Just like Jupiter and the asteroid belt, Neptune’s heft would have scattered many of these relics before a large planet could form.

And yet, fainter and fainter surveys of the outer solar system had come up empty-handed.

Finally, more than 50 years after Tombaugh added the ninth planet, technology allowed the next leap. Enter CCD cameras.

Astronomers David Jewitt and Jane Luu were early adopters of these light sensors now common to modern cameras. Astronomers already had shown there was nothing out there up to 100 times fainter than Pluto. The pair attached a large (for the era) CCD to a 2.2-meter telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii and probed deeper than ever before into this proposed third realm. Jewitt and Luu were just one of several teams using a survey technique also employed by Tombaugh to push even fainter.

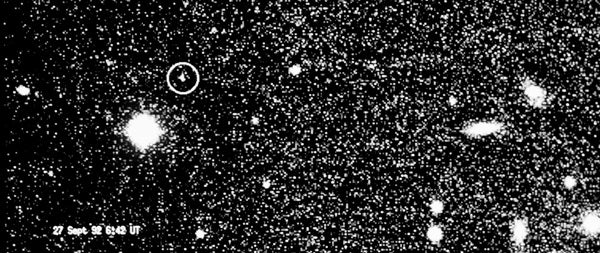

The pair hit pay dirt four years into their efforts. Pluto 2.0 came in the form of a 100-mile-wide (160 kilometers) world named 1992 QB1. Smiley, as they came to call it, was waiting 745 million miles (1.2 billion km) past Neptune, and astronomers hadn’t seen it before because it was thousands of times fainter than Pluto.

“Some solutions are compatible with membership in the supposed Kuiper Belt,” said the Minor Planet Center email announcing the possible find.

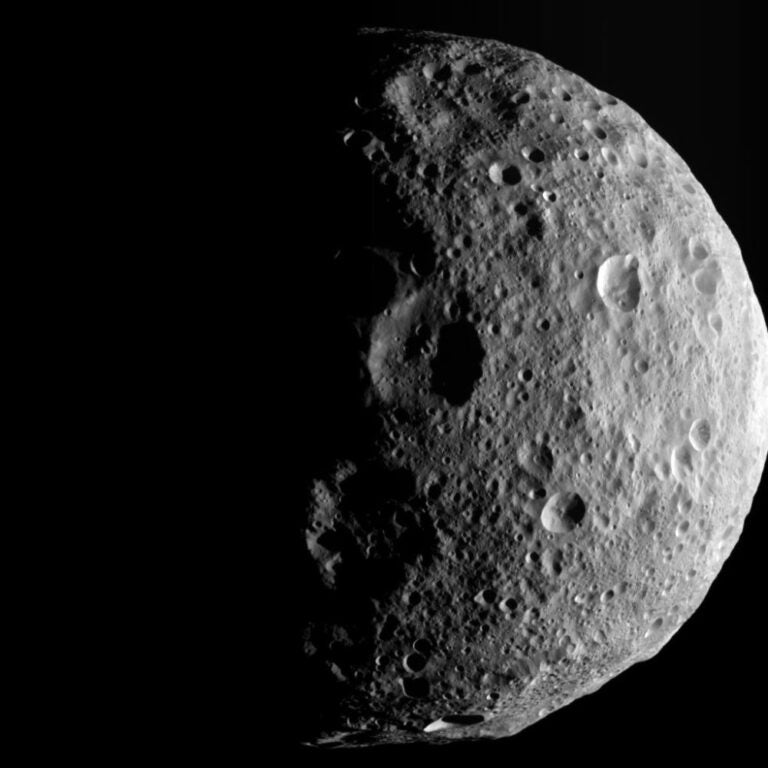

And even as Luu and Jewitt worked to refine an orbit for their new icy dwarf planet, it became clear that the floodgates had opened. The pair found another within six months, then two more. Soon, other teams were turning up even larger Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs). Today, there are 1,000 known KBOs larger than 60 miles (100km) in diameter.

Astronomers now know that Pluto was no freak, but merely the biggest and brightest example of this third planetary zone. This region includes hundreds of millions of comets and at least at one point, hundreds or even thousands of Plutos.

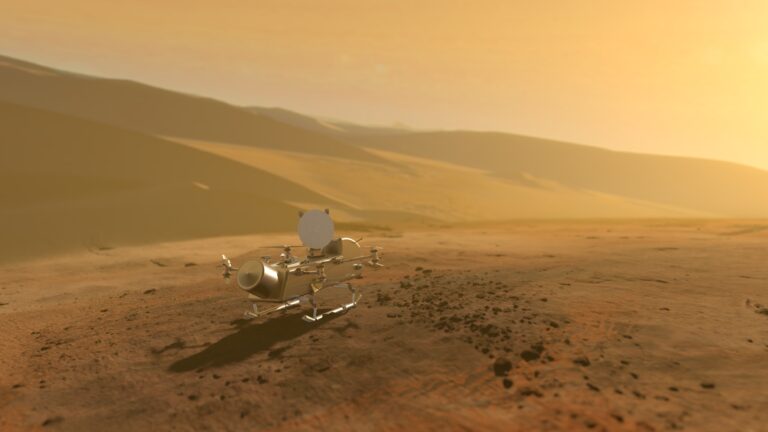

In one month, New Horizons will become the first spacecraft to visit a KBO. And, if NASA elects to continue funding for the mission into the coming years, astronomers will get a look at Pluto’s icy brethren as well.

Eric Betz is an associate editor if Astronomy. He’s on Twitter:@ericbetz.