Edwin Hubble revolutionized astronomy in 1923 when he discovered that the “Andromeda Nebula” was actually a distant island galaxy full of stars, gas, and dust. That breakthrough helped set the cosmic distance scale and the overall nature of the cosmos. But fewer astronomy enthusiasts know that a decade before Hubble’s discovery, a little-known astronomer at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, discovered the expanding universe.

Indiana youth

Vesto Melvin Slipher was born on a farm in Mulberry, Indiana, on November 11, 1875. Invariably known as “V.M. Slipher,” he had an unspectacular childhood in the American Midwest, with few details of his youth ever recorded. Certainly growing up on a farm kept Slipher in robust shape. Many years later, astronomers remarked on his ability to climb mountain peaks, staying well ahead of those who were much younger. Slipher had a brother, eight years his junior, Earl C. Slipher, who would also grow up to be an astronomer and work at Lowell Observatory.

But during Slipher’s youth, this was all a distant future dream. Slipher graduated from high school, taught briefly at a country school, and then enrolled at Indiana University in Bloomington. One of his professors was Wilbur Cogshall, who had worked as an astronomer at Lowell in 1896 and 1897. Another professor was John Miller, an astronomer who later became director of Sproul Observatory in Pennsylvania. It was Miller who turned Slipher’s interests toward the heavens and Cogshall who introduced him to the idea of moving west to work at an observatory.

Called to the West

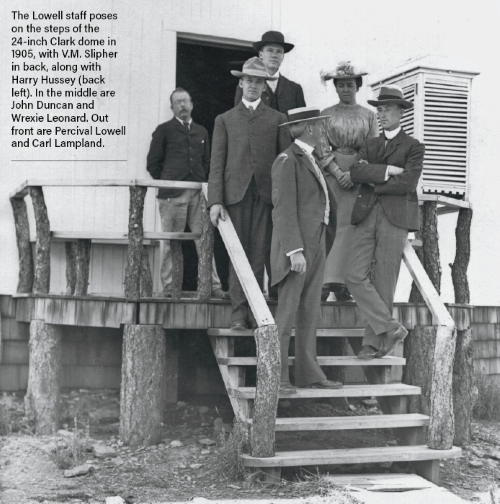

At the time, Lowell Observatory was a fledgling institution less than a decade old, overseen by its founder, the wealthy Boston adventurer-scientist Percival Lowell.

At first, Lowell was reluctant to seek Slipher’s help, but Cogshall persuaded him to bring on the young astronomer. The year was 1901, and as far as Lowell was concerned, the association would be temporary. In the end, however, Slipher would stay at the observatory for 53 years. In 1915, he became assistant director, and when Lowell died the following year, Slipher became acting director and then director by 1926. He served as the observatory’s chief until retiring in 1954 at age 79.

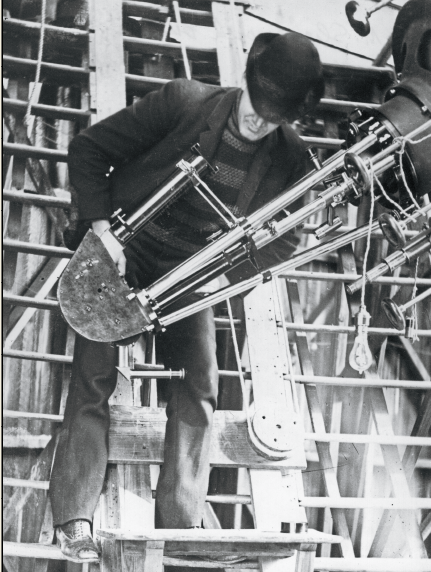

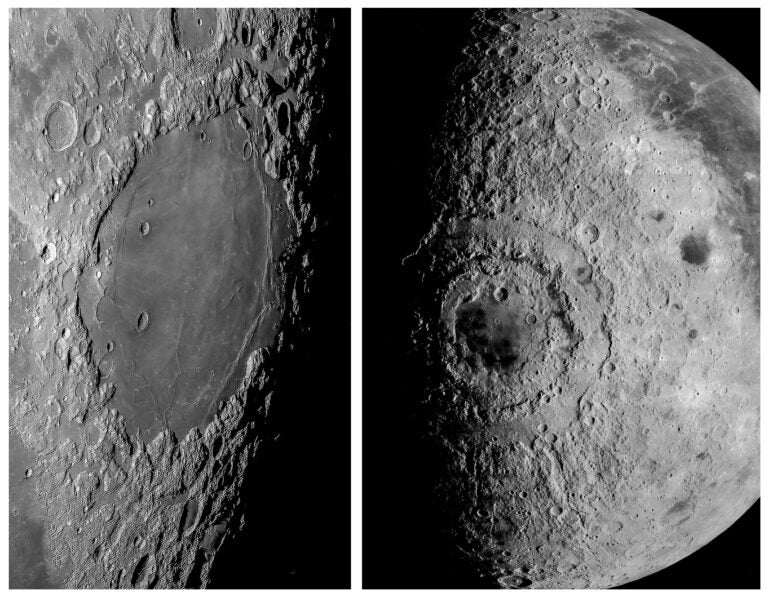

Slipher began to use this spectrograph exhaustively. He studied planetary atmospheres, such as that of Mars, and examined the rotation period of Venus. He also studied the spectra of the giant outer planets Uranus and Neptune. Attempting to determine the rotation periods and detection of various substances — such as chlorophyll on Mars — took up much of his research.

Moreover, in December 1912, Slipher used the spectrograph to discover the presence of dust — or “pulverulent matter,” as he termed it — between the stars of the famous Pleiades Cluster. Proving that the dust near the star Merope in this cluster was shining only by reflected light demonstrated the existence of stuff between the stars; that stuff came to be called the interstellar medium.

The breakthrough

The discovery of matter among the stars of the Pleiades was a big one. This put Slipher on the map, with a legitimate claim to a major discovery in astrophysics. He then turned toward solving the biggest mystery of the age, the nature of so-called spiral nebulae. These numerous, faint, diffuse objects had remained mysterious for a century and a half. The German natural philosopher Immanuel Kant had suggested they were separate, large “island universes” of matter as early as 1755. But the evidence of their nature was slow in coming. Some thought they were within the Milky Way, embryonic planetary systems in their early stages of formation.

In 1909, Slipher began recording spectra of spiral nebulae, urged on by Lowell, who thought they might show spectral similarities to our solar system. This task was difficult, however, because these objects were faint. Nonetheless, Slipher consulted with astronomers at other observatories and experimented with equipment, including faster lenses and observing techniques that might minimize the difficulty.

In the fall of 1912, Slipher recorded a plate of the “Andromeda Nebula” that he felt was sufficiently good to obtain its radial velocity. No radial velocities of nebulae were known at that time. He recorded better plates in November and December 1912, and still a better result on the nights of December 29, 30, and 31, and into the predawn hours of New Year’s Day 1913. He measured the plates over the first half of January, finding that the nebula was moving three times faster than any previously known object in the universe.

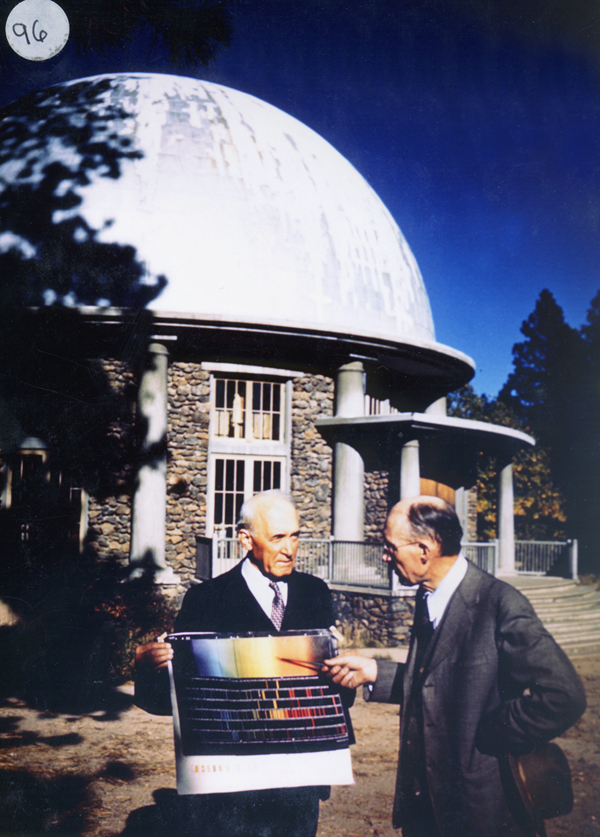

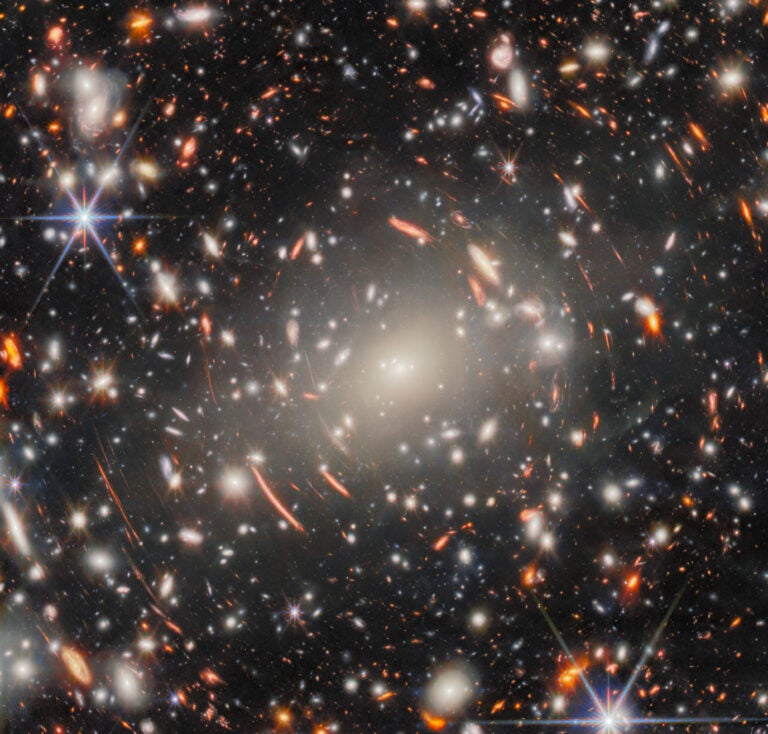

Slipher next went after what we now call the Sombrero Galaxy (M104) in Virgo. He found its spectral lines shifted far toward the red, indicating that it is receding from Earth at 620 miles per second (1,000 km per second). By the 1914 American Astronomical Society meeting in Evanston, Illinois, Slipher was able to announce results for 15 spirals. Nearly all were receding at high velocities. Three years later, Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter theorized that the universe is expanding. It was Slipher’s observations of the so-called spiral nebulae that established this fact.

Slipher’s varied work

In addition to discovering that the spiral nebulae were receding at great velocities, Slipher found that radial motions existed within the spiral nebulae themselves. That is, they were rotating. These first discoveries again included what we now know as the Andromeda and Sombrero galaxies. This finding contradicted what astronomer Adriaan van Maanen of Mount Wilson Observatory had reported earlier, that the spiral arms of these objects were unwinding. This would suggest they were close and not at great distances, or such a detection would be impossible.

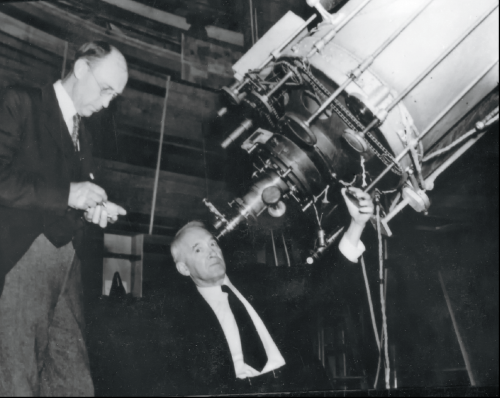

As with many aspects of astronomy, debates ensued, and most astronomers took the side of van Maanen rather than Slipher. Another decade passed before the realization came that Slipher was right and van Maanen wrong. By the end of World War I, other astronomers reinforced Slipher’s work on spiral nebulae with their own observations, and the tide of belief began to turn. And then in 1923 came Hubble’s discovery of the nature of galaxies. By 1929, Hubble derived his crucial velocity-distance relationship for galaxies, using, as Hubble wrote Slipher, “your velocities and my distances.” Slipher and Hubble had together uncovered the expanding universe, the nature of galaxies, and a way to measure extragalactic distances.

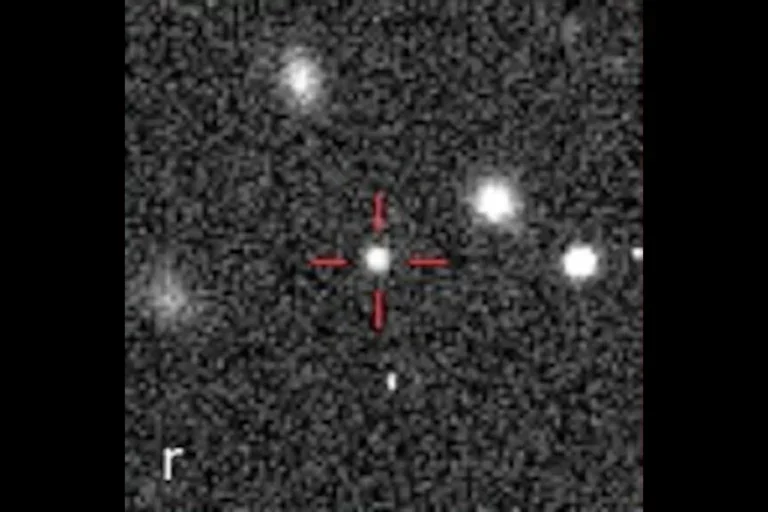

In addition, Slipher led two eclipse expeditions, in 1918 to Syracuse, Kansas, and in 1923, to Ensenada, Mexico. He also made spectral studies of unusual objects like the Crab Nebula, Hubble’s Variable Nebula, and the unusual nebula NGC 6729. He supervised the search for a new outer solar system planet, bringing on board Clyde Tombaugh, a young Kansas farm boy, who would in 1930 find Pluto.

But Slipher will be remembered for his discoveries relating to spiral nebulae and the expanding universe. When he received the Royal Astronomical Society’s Gold Medal in 1933, the president said: “In a series of studies of the radial velocities of these island galaxies he laid the foundation of the great structure of the expanding universe. … If cosmogonists today have to deal with a universe that is expanding in fact as well as in fancy, at a rate which offers them special difficulties, a great part of the blame must be borne by our medalist.”

When it comes to the expanding universe, the rotation of galaxies, the discovery of the interstellar medium, important studies of aurorae and sky glow, and other areas, we should not forget the name V.M. Slipher. Edwin Hubble helped us define galaxies. His associate Slipher gave us universal expansion, a concept that governs the mighty cosmos.