In the U.S., President Richard Nixon was still grappling with the Vietnam War, declaring that the combat mission of American troops would end by the coming summer. The administration’s criminal activities, which would ultimately result in the Watergate scandal, were already underway, though as yet undetected. The cultural leaders of the rock ‘n’ roll movement, the Beatles, had broken up, leaving a wide-open and uncertain future for the leading edge of pop music. The pure idealism of the ’60s seemed faded; the hippie culture had subsided and, although no one quite knew it yet, the “me decade” of self-interest was already rolling forward. In the Soviet Union, the space program kept moving, but the momentum for a crewed lunar program was now completely gone.

Meet the crew

To lead the first Apollo mission of 1971, NASA turned to a wily veteran. Alan Shepard had been the first American in space, making his suborbital flight May 5, 1961, just 20 days before John F. Kennedy’s speech calling for a mission to land on the Moon. Shepard, age 47, was born in New Hampshire and had a distinguished career as a naval aviator and test pilot before his Mercury flight in Freedom 7. Now he was slated to be the commander of Apollo 14; this would make him the oldest person ever to walk on the Moon, as well as the only Mercury astronaut to accomplish this feat.

Joining Shepard would be Command Module Pilot Stuart Roosa and Lunar Module Pilot Edgar Mitchell. Shepard’s spaceflight experience would be especially valuable: Both Roosa and Mitchell were rookies, having never yet flown in space. Roosa, age 37, was an aeronautical engineer, Air Force pilot, and test pilot. He was born in Colorado and achieved an impressive military record before being chosen as one of NASA’s astronaut class of 1966. Mitchell, age 40, was a Navy officer and aviator, test pilot, and aeronautical engineer. Born in Texas, he was also selected in the 1966 astronaut group, and had served in support teams on previous Apollo missions before his assignment to Apollo 14.

The mission’s backup crew consisted of Gene Cernan, Ronald Evans, and Joe Engle. (Later, with Harrison Schmitt substituting for Engle, this crew would become the primary one for the final Apollo mission.)

Changes ahead

Apollo 14’s Command/Service Module was nicknamed Kitty Hawk and the Lunar Module (LM) Antares. Following Apollo 13, NASA engineers modified the electrical power system of the Service Module, attempting to minimize the risk of any further malfunctions. The team redesigned the oxygen tank in which an errant spark had caused the explosion when Swigert switched on the stirring fans. They added a third tank as well. Confidence in the new design was high.

The launch date for Apollo 14 was originally set for Oct. 1, 1970. But Apollo 13 changed the timetable, pushing it back. The new launch date for Apollo 14 was scheduled for Jan. 31, 1971, and the mission was to aim again at the region of Fra Mauro, the area targeted by the aborted Apollo 13. This region of highlands, named after the crater lying within it, consists largely of ejecta from the immense impact that created the nearby Mare Imbrium. Studying this hilly geological area would provide insights on the formation of Mare Imbrium. Furthermore, the debris covering the ejecta was thought to consist of exposed older rocks from deep below. Retrieving them might allow the explorers to uncover some secrets about the Moon’s geological history; now the Apollo missions were evolving from simple exploration and wonder at just being on the lunar surface to a deeper and more organized program of scientific studies.

Bumpy beginnings

The January launch took place right on schedule, despite heavy cloud cover that hung over Kennedy Space Center. With U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew on hand, along with Spanish Prince Juan Carlos and his wife, Princess Sophia, the Saturn V jumped skyward and quickly out of sight into the clouds. The spacecraft achieved Earth orbit, and Shepard separated the Command/Service Module from the Lunar Module and turned the former around for docking.

Then the mission had its first hint of trouble. The astronauts undertook the docking procedure multiple times, having trouble each time completing the maneuver. Finally, after more than an hour and a half, Roosa tried holding Kitty Hawk against Antares with its thrusters while simultaneously retracting the docking probe. The docking latches took hold, accomplishing the procedure. There was a sigh of relief following the close call — an inability to connect the Command and Lunar Modules was potentially a major problem.

On Feb. 4, Apollo 14 concluded its glide phase over the 240,000-mile (386,000 kilometers) trip to the Moon. Entering lunar orbit, the spacecraft seemed fine. The following day, Shepard and Mitchell climbed into the LM and prepared for their descent to Fra Mauro. Roosa would stay within Kitty Hawk, piloting it as it circled the Moon.

Soon after beginning the descent within Antares, the astronauts encountered a problem. The lander’s computer signaled an “abort” alert, which they determined was a false alarm due to a faulty switch. But if the alarm were to recur after the descent engine began firing, the computer would treat the false alarm as if it were real and abort the descent. This would cause the craft’s ascent stage to ignite and separate from the descent stage, and the LM would return to a lunar orbit.

Back at Mission Control, the flight team enlisted engineers at NASA and at MIT to work on the problem. After a short time, engineers suggested reprogramming the computer onboard Antares to ignore the abort signal. Mitchell frantically entered the changes into the computer. It worked, allowing the descent to begin. “It’s a beautiful day to land at Fra Mauro,” said Shepard in response to the fix.

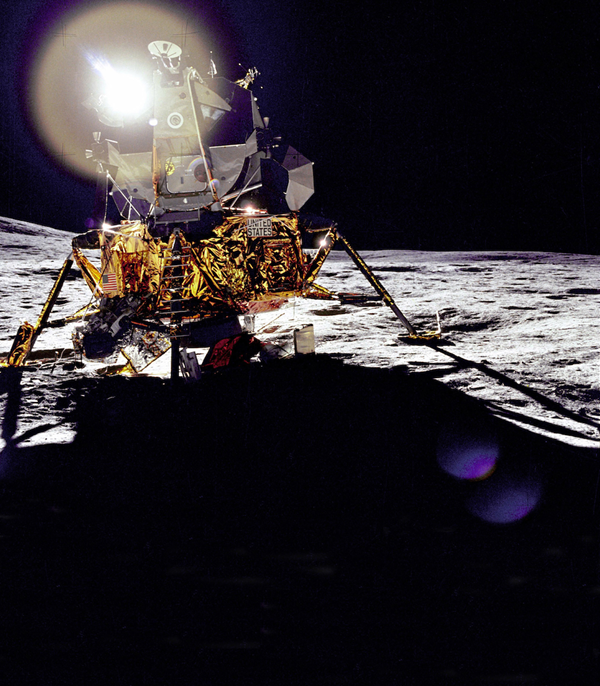

But another problem cropped up. The landing radar employed by Antares failed to recognize the lunar surface, so that altitude and vertical speed data would not show in the LM. The fix this time seemed to be cycling through the craft’s radar breakers. At an altitude of about 18,000 feet (5,490 meters), the data readouts came back on, allowing the astronauts to safely pursue the landing. The spacecraft pitched over and Shepard and Mitchell began to see landmarks on the Moon. “There it is,” said Shepard upon spotting Fra Mauro as he manually landed the LM. “It’s really a wild-looking place here,” said Mitchell. The craft ultimately came to a halt just where they had planned. In fact, Shepard’s landing came closer to the chosen point than any of the other five lunar landings.

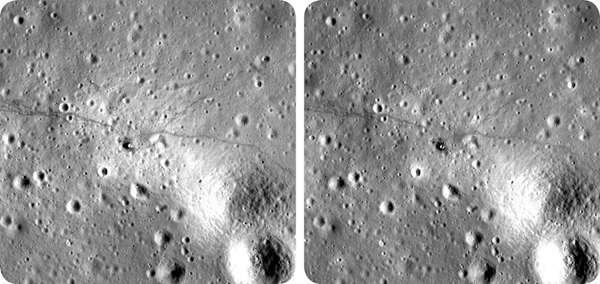

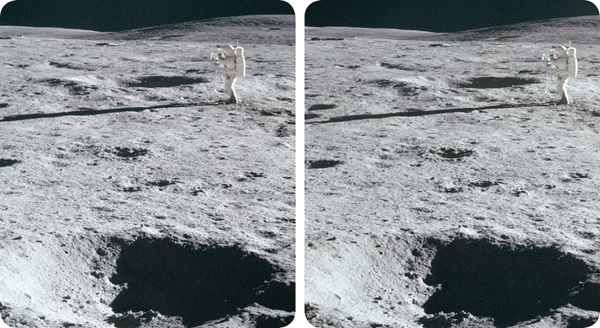

How to view our 3D images

There are two ways to view the images printed in 3D. To free view the images with no mechanical assistance, let your eyes relax as you view the photos as though focusing on a point behind them. At first you will see the two images split into four; as your eyes focus at the correct distance, the middle two images will combine to create a single, crisp 3D image. The outer two images will remain on either side of the 3D image and become blurry.

Alternatively, you can use a 3D viewer, such as the Lite OWL viewer designed by Brian May and included with the Mission Moon 3-D book, to view images in 3D. Only 5 by 2.5 inches (134 by 64 millimeters) and 0.1 inch (3 mm) thick, the Lite OWL viewer is designed for easily viewing 3D images in books, magazines, modern and vintage stereocards, and even video or other VR content on your smartphone. You can purchase individual Lite OWL viewers separately at www.MyScienceShop.com

Lunar activities

On Feb. 5, Shepard and Mitchell made their first of two moonwalks, which would last between four and a half and five hours each. They named the lunar base at their landing position Fra Mauro Base, which was subsequently added to lunar maps showing the Fra Mauro region. As he descended the LM ladder and finally touched the lunar surface with his heavy boot, Shepard said, “And it’s been a long way, but we’re here.” This was the third “first step” of a lunar explorer on a new mission — the first two steps those of Neil Armstrong and Pete Conrad.

Unlike Apollo 12, this time, the astronauts successfully employed their color television camera, which they planted on the surface at Fra Mauro Base, along with the customary U.S. flag. There would now be broadcasts in natural color showing the astronauts during their moonwalks and activities. NASA had not been satisfied with the appearance the previous missions’ pictures, in which it was difficult to differentiate between astronauts. So this time, Shepard wore an Apollo suit that had red stripes on the arms and legs, enabling easy identification of the commander. NASA continued this practice with the remaining Apollo flights and into the era of the space shuttle.

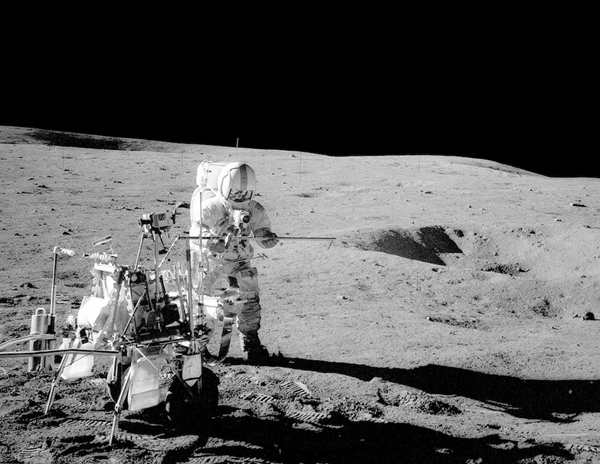

As with the previous missions on the lunar surface, the astronauts deployed the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package, or ALSEP, which contained experiments that would record data on seismology, magnetism, the solar wind, heat flow, and the abundance of ions. They also deployed the Modular Equipment Transporter, a pull cart for transporting equipment and Moon rocks. The astronauts nicknamed the cart the “lunar rickshaw.”

The first moonwalk lasted nearly four hours and 48 minutes. It succeeded in all the astronauts hoped to accomplish. Some 13 hours after the first walk ended, the astronauts commenced their second extravehicular activity. Shepard again set foot onto the lunar surface first, followed by Mitchell some seven minutes later. During the second walk, the astronauts planned to walk to Cone Crater, a 1,000-foot-wide (300 m) depression in Fra Mauro.

As the grade angled slightly uphill, Mitchell noted that the walk was a little more exerting. “We’re starting uphill now,” he said. “It’s definitely uphill.” Shepard and Mitchell stopped short of the crater by about 100 feet (30 m) and collected a substantial amount of lunar rock and soil samples. Mission planners believed these would be of particular interest geologically because they had been blasted up from deep below the surface.

As the pair continued walking, Shepard noticed how dusty the lunar surface was — how dust was getting kicked up and adhered to the spacesuits. “Nothing like being up to your arms in lunar dust,” he said.

Shepard plopped a golf ball onto the lunar surface. He was an avid golfer and had planned this surprise as a test of his own abilities on the Moon’s surface as well as a test of the weaker lunar gravity relative to Earth. “Unfortunately, the suit is so stiff, I can’t do this with two hands,” he said. “But I’m going to try a little sand trap shot here.”

The Apollo 14 commander took a swing, knocking some lunar dust skyward. “Hey, you got more dirt than ball,” said Mitchell. Watching from back on Earth, Fred Haise — recovered from his infection during Apollo 13 and acting as a CapCom (capsule communicator) on the ground — said, “That looked like a slice to me, Al.”

“Here we go again,” said Shepard as he swung again. “Straight as a dime. Miles and miles and miles.” Shepard later concluded that the golf ball traveled between 200 and 400 yards (180 and 370 m). Not to be outdone, Mitchell thrust a lunar scoop handle in the air as if it were a javelin, in what could perhaps be called a Micro Lunar Olympics.

They concluded the second moonwalk after collecting some 94 pounds (43 kilograms) of Moon rocks. After 33.5 hours total on the lunar surface and nine and a half hours walking around, the pair prepared to blast off and return to Kitty Hawk, with Roosa still orbiting overhead.

Kitty Hawk splashed down in the Pacific Ocean south of American Samoa, and the astronauts recovered well from the ordeal. In the wake of the scare over Apollo 13, the Apollo program was solidly back on the right track, and the samples collected and science that had been conducted would help the Moon program enormously.

Two space programs

The Soviet Union’s ongoing space program now essentially consisted of watching the Americans run away with the lunar prize. The Soyuz program continued, but these flights were Earth orbital missions. Through 1970, eight Soyuz missions had taken place, some with rendezvous objectives and others paving the way for coordination with the planned Salyut 1 space station — the world’s first space station, to be deployed by the spring of 1971. The launch of this very significant first was planned to mark the 10th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s flight, but in the end had to be delayed by several days.

The first mission to Salyut 1 was Soyuz 10, launched April 22, 1971. The crew — Vladimir Shatalov, Aleksei Yeliseyev, and Nikolai Rukavishnikov — hoped to rendezvous with Salyut 1 and board the space station, becoming the first station crew in space exploration history. But the docking with Salyut 1 was unsuccessful and the crew had to return to Earth.

Several months later, another crew set off for Salyut 1. Soyuz 11, with cosmonauts Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev, blasted off from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, on June 6 and docked with Salyut 1 one day later. The cosmonauts remained on board the space station for 22 days, setting an endurance record in space that would stand for another two years.

When they entered the station, the crew discovered a smoky smelling atmosphere. On the 11th day in the station, a small fire broke out. The cosmonauts had hoped to observe a rocket launch from the station, but it was delayed. Nonetheless, they made a TV broadcast back to Earth and generally enjoyed the stay.

Tragically, when the capsule was recovered on Earth after landing June 30, the mission recovery team opened it to find all three crewmembers dead. The cosmonauts had bluish patches on their faces and had hemorrhaged from their mouths and noses. The official cause of death was given as asphyxiation. The original commander of the mission, Alexei Leonov, had advised the crew from the ground to close valves between the orbital and descent modules manually, because he did not trust the automatic mechanism. The cosmonauts did not follow his suggestion, however, and this may have been the cause of the fatal event.

Although the Soviet program would not land cosmonauts on the Moon, it made important contributions to lunar science. And underneath the veil of the space race, something else was happening. Alongside the direct competition, Soviet and American space explorers were forming a partnership that would become stronger and stronger as the months and years passed, even as the U.S. planned its next Moon mission: Apollo 15.

Mission Moon 3-D: A New Perspective on the Space Race

, by David J. Eicher and Brian May (with foreword by Charlie Duke and afterword by Jim Lovell), presents the story of the historic lunar landings and the events that led up to them, told through text and three-dimensional images.Mission Moon 3-D contains new and unique stereoscopic images of the Apollo Moon landings to show what it was like to walk on the lunar surface. The triumph of the Apollo 11 Moon landing takes center stage, with detailed stories and visually stunning images from the lunar missions that followed. The book includes 150 stereo photos of the Apollo mission and space race — the largest group ever published — and presents photos never seen before in stereo.

The book delivers a comprehensive tale of the space race. New stories appear from the astronauts, including Jim Lovell’s anecdotes about the perilous return of Apollo 13.

Mission Moon 3-D also includes a history of the music and special movements of the 1960s and beyond that transformed the world, from Vietnam and Woodstock to Live Aid. Don’t miss out on this unique treasure