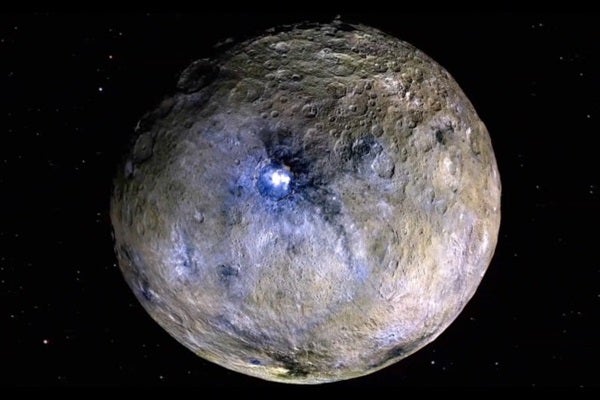

Remnants of an ancient water ocean are buried beneath the icy crust of dwarf planet Ceres — or, at least, lingering pockets of one. That’s the tantalizing find presented August 10 by scientists working on NASA’s Dawn mission. Their research was laid out in a series of papers published in Nature.

By far, Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt, which girdles the inner planets between Mars and Jupiter. But unlike its rockier neighbors, Ceres is a giant ice ball. It holds more water than any world in the inner solar except for Earth. That knowledge had long led some astronomers to suspect Ceres may have once had a subsurface ocean, which is part of the reason NASA sent the Dawn spacecraft there.

However, some models predicted that Ceres’ ocean would have frozen long ago, forming the world’s thick, icy crust.

Now, after five years studying a series of strange surface features around recently-formed craters, astronomers believe they’re seeing signs of a large, subsurface body of briny liquid. Variations in Ceres’ gravitational field back that up, implying that the underground reservoir of salty water may stretch horizontally beneath the ice for hundreds of miles and reach depths of roughly 25 miles (40 kilometers).

“Past research revealed that Ceres had a global ocean, an ocean that would have no reason to exist [still] and should have been frozen by now,” study co-author and Dawn team member Maria Cristina De Sanctis of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome tells Astronomy. ”These latest discoveries have shown that part of this ocean could have survived and be present below the surface.”

If future missions can confirm the results, it will mean that there’s a very salty, very muddy body of liquid somewhere around the size of Utah’s Great Salt Lake on a dwarf planet that’s just 590 miles (950 km) across — roughly the size of Texas.

Astronomers believe that the extreme saltiness of the water, which lowers its freezing point, has helped it remain a liquid for so long. Also, a class of compounds called hydrates, which are cages of water that trap gas or salt compounds, can change the way that heat moves through the dwarf planet’s crust.

Researchers used similar reasoning, applying it to data from NASA’s New Horizons mission, to also argue that Pluto hides a global liquid water ocean beneath its icy crust.

“Oceans should be common features of dwarf planets based on what New Horizons learned at Pluto and Dawn at Ceres,” Dawn project scientist Julie Castillo-Rogez of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who co-authored one of the studies, tells Astronomy.

The new find raises interesting questions about whether Ceres could be habitable by alien life. And it could put Ceres among a rapidly-growing group of potential icy ocean worlds that have been revealed in recent years.

Ceres is the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system, and it locks up one-third of the entire mass in the asteroid belt. Astronomers think Ceres is a protoplanet, the fossilized remains of a world that never fully formed. But its growth was halted before it could become a full planet. Having such a history means Ceres likely holds an early record of our solar system’s primordial past — hence the name Dawn.

Ceres’ strange white spots

The Dawn mission was launched in 2007 with an unconventional ion engine that let it first orbit Vesta, the asteroid belt’s second largest object, for 14 months before venturing on to Ceres in 2012. No single mission had ever orbited two extraterrestrial worlds before.

“Vesta is a dry body almost like the Moon,” Dawn Principal Investigator Carol Raymond of JPL tells Astronomy. “Ceres we knew was a very water-rich object that had retained volatiles from the time it had formed. The two were sitting there like plums. The low-hanging fruit.”

Ceres started to tease its secrets to astronomers with Dawn’s first glimpses of the dwarf planet in early 2015. A pair of weird white spots stood out from afar, shining like cats’ eyes in the dark. More of these bright features became apparent on approach, and they ended up at the center of scientists’ efforts to understand Ceres.

Much of Ceres’ story was apparent within just a few of Dawn’s arrival, but scientists still felt they had more to learn, so NASA extended Dawn’s mission for a second run. This let the spacecraft keep collecting data until 2018, when it finally ran out of fuel. This latest batch of research was collected during that extended phase.

And as Dawn gathered higher resolution images, it started to unravel intimate details of the world’s surface and its ancient history. Among other things, the spacecraft spotted a lone mountain that stretches some 21,000 feet (6,400 meters) above the surface, taller than Denali, North America’s tallest peak.

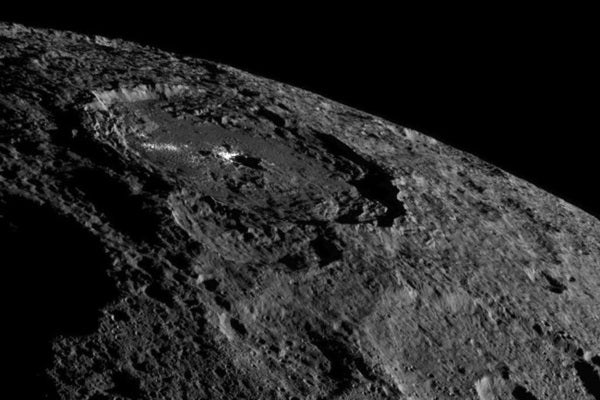

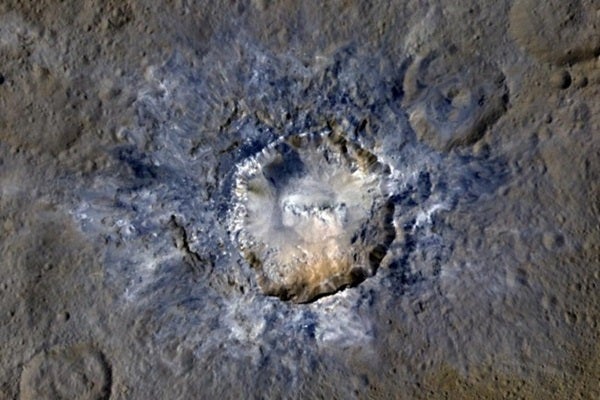

Ceres’ white spots sit inside Occator Crater, which stretches across 57 miles (92 kilometers) of the world’s northern hemisphere. Another place with a prominent bright spot is within smaller Haulani Crater, named for the Hawaiian goddess of plants. It’s one of the dwarf planet’s youngest features.

According to the research, it seems that when impacts struck this region, it penetrated into a reservoir of muddy, salty water buried beneath the plain.

In one of the papers published on August 10, a team of scientists unravel the history of Occator Crater in detail. They believe a space rock struck this location some 20 million years ago, puncturing the icy crust down into the salty reservoir below. Within hours, though, the crater quickly froze over.

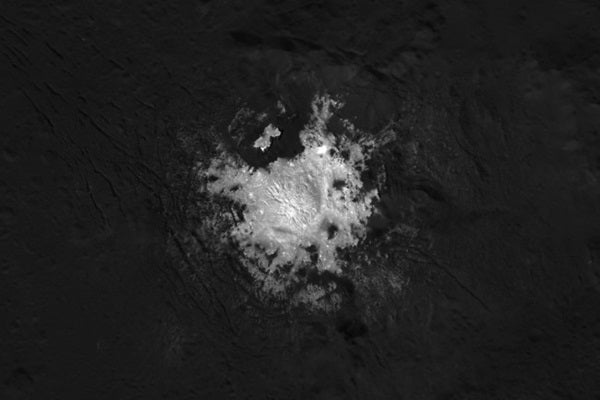

However, when it did, it sealed in a large chamber of melt water beneath the center of the crater, letting fluids and chemicals continue to mix with the larger reservoir below. This structure allowed salty, chemical-rich water to erupt from the center of the crater as recently as 2 million years ago, creating the fascinating white spots.

However, Ceres could have erupted even more recently than that. Before Dawn reached the dwarf planet, the European Space Agency’s Herschel Telescope detected water vapor coming from the same region. And if fluids aren’t still seeping out of the cracks in Occator Crater, then the minerals in the area should have evaporated already.

“It’s really kind of a smoking gun, because you would have expected it had gone away if it had been sitting there even close to the surface for millions of years,” Raymond says.

Ceres as an abode to life?

Scientists still aren’t totally sure what Ceres has in common with the other icy ocean worlds of our solar system, like Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus. However, some of the minerals found on Ceres have also been found within the plumes of water erupting from Enceladus, drawing some connection between the two bodies.

All these finds taken together are changing astronomers’ ideas about our solar system. Half a century ago, they thought Earth’s oceans made it a unique abode for life in our solar system. But it now appears there could be dozens of potential ocean worlds in the inner and outer solar system. That finding is “one of the most profound discoveries in planetary science in the space age,” S. Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute and head of NASA’s New Horizons mission, tells Astronomy.

In the decades to come, astronomers are pushing for a host of missions to explore these ocean worlds in more detail. And Ceres’ relatively close proximity to Earth could help them make the case for a visit in the not-so-distant future.

On Monday, as the team’s new research was being published, Castillo-Rogez formally submitted a study outlining a $1 billion mission that would actually land on Ceres. If astronomers voice interest in the idea as part of their decadal survey, and NASA decides to fund it, the spacecraft would fly sometime before 2032 as a New Frontier class mission. Meanwhile, the European Space Agency is also studying a potential sample return mission.

“Ceres is a lot closer and it’s a lot easier to get to than these moons in the outer solar system,” Raymond says. “So it is a very enticing target.”