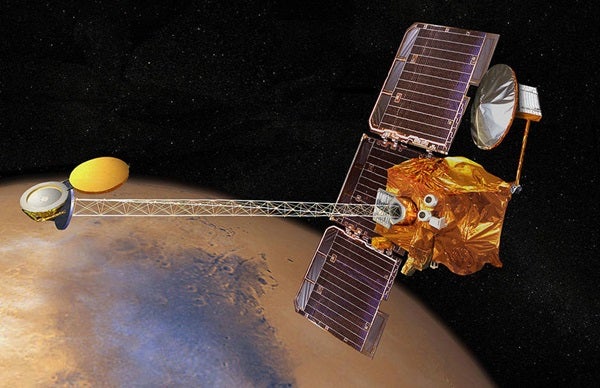

For more than 20 years, NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter has been circling the Red Planet, mapping the martian surface to help astronomers untangle the mysteries of Mars’ history.

But in January 2022, engineers calculated that Odyssey only had enough propellant to last about 12 more months. It appeared that after traveling some 1.37 billion miles (2.21 billion kilometers) and looping around the Red Planet more than 94,000 times, Odyssey’s mission would soon come to a close.

Fortunately, that’s no longer the case. According to a recent NASA news release, new estimates suggest Odyssey actually has enough remaining propellant to last through at least the end of 2025.

A spacecraft without a fuel gauge

Mars Odyssey orbiter launched in 2001 with nearly 500 pounds (225 kilograms) of hydrazine propellant. In order for Odyssey to keep its science instruments trained on the martian surface, the spacecraft depends on three spinning reaction wheels to create internal torque.

“These reaction wheels have to work together to maintain the spacecraft’s pointing,” Jared Call, Odyssey’s mission manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), said in the release. “But with Odyssey completing a full loop every orbit, you need a way to unload the increasing momentum.”

That’s where Odyssey’s thrusters and the hydrazine propellant come into play. In order to counteract the building momentum of the reaction wheels, the spacecraft’s thrusters fire out hydrazine propellant in short bursts.

(Mis)measuring Odyssey’s fuel supply

Unfortunately, Odyssey does not come equipped with a fuel gauge, which means engineers have to get creative when estimating how much propellant the spacecraft has left.

One way they do this is by applying heat to the spacecraft’s two propellant tanks. The more hydrazine left in the tanks, the longer it should take for the tanks to heat up to a certain temperature.

In the summer of 2021, this method yielded an estimate of 11 pounds (5 kg) of propellant remaining. Another calculation in January 2022 showed just 6 pounds (2.8 kg) of hydrazine remaining.

These results caught engineers by surprise. If the numbers were accurate, the spacecraft must have experienced some sort of failure or leak. And if that was the case, Odyssey would be dead in space within a year.

A new estimate of Odyssey’s remaining fuel

In order to figure out what was really going on with Odyssey’s propellant supply, NASA engineers reached out to Lockheed Martin Space, which built the craft, maintains mission operations, and provides engineering support.

“First, we had to verify the spacecraft was OK,” said Joseph Hunt, Odyssey’s project manager at JPL. “After ruling out the possibility of a leak or that we were burning more fuel than estimated, we started looking at our measuring process.”

To do this, NASA and Lockheed opted to bring in an outside consultant, Boris Yendler, who specializes in spacecraft propellant estimations. Yendler wondered whether Odyssey’s heaters, which are intended to keep various parts of the spacecraft warm, could be throwing off the calculations by heating the hydrazine more quickly than anticipated.

After a number of experiments, the team confirmed Yendler’s hypothesis was correct. The heaters, which are located next to the fuel lines that connect to the propellant tanks, were warming up the tanks faster than expected. This made it seem like the tanks had less hydrazine left in them then they really did.

“Our method of measurement was fine. The problem was that the fluid dynamics occurring on board Odyssey are more complicated than we thought,” Call said.

After accounting for the heaters, revised calculations recently showed that Odyssey actually has about 9 pounds (4 kg) of hydrazine left, which is enough to last through 2025.

“It’s a little like our process for scientific discovery,” said Call. “You explore an engineering system not knowing what you’ll find. And the longer you look, the more you find that you didn’t expect.”